An Unusual Existence in the City

1. Introduction

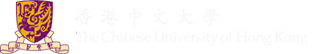

The project explores one of Hong Kong’s best recognised cultural landmarks, Chungking Mansions, in the highly accessible central business district of Tsim Sha Tsui (Figure 1). Surrounded by many luxurious hotels and high-end shops, Chungking Mansions stands out as a vertical cluster of small businesses and guesthouses, where ethnic minorities ranging across traders, workers, tourists and asylum seekers converge. This earns Chungking Mansions the name “Ghetto at the Center of the World”, after the title of Gordon Mathews’s (2011) seminal anthropological account of the building.

Chungking Mansions and its Surrounding Area

Why can we find Chungking Mansions as a “ghetto” in Tsim Sha Tsui, where land rent is sky high? How is the cultural – particularly ethnic – complexity inside the building embedded within Hong Kong’s geographical context? These are the questions this project attempts to address from a cultural geographical approach, with the aid of Henri Lefebvre’s theory of spatial triad.

Theoretical Approach: Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad

A cultural geographical approach analyses the diversity of symbolic and material practices of human communities as cultural traces – outcomes of interaction between culture and the geographical context in which these traces are found. Accordingly, this project takes Chungking Mansions as a cultural trace produced through the interactions between its many stakeholders (e.g., property owners, vendors, visitors, etc.) from diverse cultural backgrounds on one hand, and the socio-spatial context of Hong Kong evolving over time.

Proposed by French sociologist Henri Lefebvre, the theory of spatial triad offers a framework to systematically analyse how cultural traces are produced through: (i) interactions between actors with different social status over space, and (ii) interactions between these actors and the space for which they compete. As its name suggests, the theory draws attention to three analytical dimensions, “representations of space”, “representational space”, and “spatial practice”. The following table explains their meanings and their application in the subsequent analysis of Chungking Mansions.

Analysing Chungking Mansions through Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad (Source: Compiled based on McCann, 1999)

|

Dimension |

Definition |

Example |

Analytical focus in Chungking Mansions

|

|

Representations of space |

Spatial imaginations of those in power, regulating how space should be ordered and used |

Official zoning plan for a city |

Government policies and property owners’ decisions which shape the physical layout, functions, and ethnic composition of the building (Section 3.1)

|

|

Representational space |

Symbols imbued in space by people living in it, often for challenging existing representations of space

|

Artistic representation (e.g., movie) of a city |

Attitudes of different people towards the building (Section 3.3) |

|

Spatial practice |

Physical space and the everyday routines and experience of people living in it

|

Actual spatial activities in a city |

Physical features, everyday activities, and social relations in the building (Section 3.2) |

Chungking Mansions as a Complex Cultural Trace

Why has Chungking Mansions developed into an ethnic enclave?

For many outsiders of Chungking Mansions, the most observable phenomenon in the building is the gathering of people from diverse ethnic backgrounds, mostly South Asians and Africans. This is made possible by three ways Hong Kong was, or is, politically and institutionally positioned in the world (Mathews, 2011).

First, the significant presence of ethnic South Asians can be traced back to the early history of Hong Kong as a British colony, which began in 1841. Back then, the Indian Subcontinent was also under British rule. Some South Asians came to Hong Kong as recruits of the British Army and the city’s colonial government, while others as traders and labourers.

Second, people from various parts of the world are drawn to Hong Kong as an international commercial centre. Located midway between the Chinese mainland and Southeast Asia, Hong Kong has developed as a gateway for traders to multiple rapidly emerging economies. Notably, more African entrepreneurs can recently be seen in Hong Kong as they visit the city to buy Chinese products for resale in their home countries.

Third, consolidating its geographical advantage in trade development, Hong Kong champions free trade and adopts visa-free policies for many nationals to facilitate flows of goods and people. These moves attract for Hong Kong not only traders and tourists from many countries, but also attract asylum seekers and foreign illegal workers.

With these factors in mind, a more specific question comes: Why do all these people from diverse backgrounds specifically cluster in Chungking Mansions? For South Asians, this might be a matter of following the choice of their early settlers in Hong Kong, many of whom concentrated in Tsim Sha Tsui. However, more generally, this has to do with the building’s availability of affordable spaces for business and accommodation.

Trace of South Asian community in Tsim Sha Tsui: Halal meat store

Built in 1961, Chungking Mansions boasts a total of 920 co-owners (Mathews, 2011, p. 38), as it is partitioned into multiple units conveyed to different parties. Given the building’s extremely fragmented ownership, it has been difficult for individual co-owners to pool together enough ownership shares to sell the building for redevelopment. As the building deteriorates, co-owners can only lease their units a low rent. In a visit to the building in 2017, we learnt that the monthly rent of a shop selling phones and accessories is only about HKD 17,000. Such low-cost space is ideal for ethnic minority migrants, who come to Hong Kong with financial difficulties, to make a living with a small business.

How do people make a living in Chungking Mansions?

Chungking Mansions is divided into three distinct clusters of different functions. For the stores mentioned above, they are found in the building’s first two floors, each as a separate cluster. The first floor is home to stores selling SIM cards, food, clothes and other daily necessities, and several money exchange stores, while the second floor is dominated by stores selling electronic gadgets. Meanwhile, the third floor and above is the territory of guesthouses and restaurants.

Chungking Mansions as a cluster of guesthouses

Guesthouses in Chungking Mansions have been known for their affordability. They first came to significant attention in the 1970s, after being featured in the famous travelling guidebook “Lonely Planet” for accommodating backpackers at very low prices (Mathews, 2011). Since the 1980s, they have blossomed within Chungking Mansions through partitioning of apartments, meeting demand from tourists with a tight budget and traders from developing economies for low cost accommodation. This contributes further to the large number of ethnic minorities in the building.

The significance presence of ethnic minorities, however, has not resulted in elaborative display of ethnic or religious features in Chungking Mansions. This is because of two reasons. Firstly, limited floor space makes it impractical to do so. Secondly, some owners are concerned that religious items may not be welcomed by everyone and thus not beneficial to their businesses.

Indeed, the economic imperative can push even the most fundamental religious principles out of consideration. According to the Quran, alcohol is prohibited for Muslims. Surprisingly, one of the Muslim restaurants we came across was selling beer to customers. “Since we just have to make a living, Allah will understand,” the boss of the restaurant shared.

What does Chungking Mansions mean to its outsiders and insiders?

To many local Chinese, Chungking Mansions is unwelcoming and dangerous. This impression stems not only from the building’s sizeable ethnic minority population which they are unfamiliar with, but also a 1994 Hong Kong movie entitled “Chungking Express”. Directed by the renowned filmmaker Wong Kar-wai, the movie depicted Chungking Mansions as a place where only people with complicated backgrounds or gangsters would go. It has had a huge impact on the public in terms of engendering and spreading the impression of the building as a “prohibited land”.

However, to the many ethnic minorities residing or working in it, Chungking Mansions is rather their ‘beacon of hope’ (Mathews, 2011, p. 16). Popularly associated with a sense of insecurity, Chungking Mansions has faced downward pressure for the rental level of its retail units. While this is hardly pleasing to the buildings’ many co-owners, it is good news to migrants and traders from the developing world, who are finding a gap in a global capitalist system working against the interest of their countries and them. To them, given the relatively low cost of finding refuge and doing business in it, Chungking Mansions stands as the best place for them to climb up the social hierarchy through their hard work, eventually overcoming the poverty and discrimination they currently suffer.

Conclusion

This project has attempted to deploy Henri Lefebvre’s theory of spatial triad to unpack how Chungking Mansions represents a cultural trace produced through three aspects of interaction between it as a multi-storey architectural space and various actors. First, territory-wide policies and rental decisions of property co-owners promote the concentration of ethnic minorities with developing world origins in Chungking Mansions. Second, some ethnic minorities are becoming less unusual as they prioritise economic pragmatism over their religious traditions. Third, despite the previous point, personal perception among some local Chinese and cinematic representation continue to obscure Chungking Mansions’ value to support the struggle of ethnic minority individuals to achieve prosperity, thereby keeping the building behind a sense of unusualness.

References

Mathews, G. (2011). Ghetto

at the centre of the world, Chungking Mansions, Hong Kong. Hong Kong,

China: Hong Kong University Press.

McCann, E. J. (1999) Race, Protest, and public space:

contextualizing Lefebvre in the U.S. city. Antipode, 31(2):2,

p.163–163-184.

A Study of Mong Kok’s evolving spaces through Lefebvre’s spatial triad

Foreword

The research project pays homage to the street culture of Mong Kok pedestrian zone, which has been permanently closed down on 31 August 2018 due to overwhelming noise pollution. This research project was conducted from September to December 2017, shortly before its closure. It is believed that the project could show the glimpse of Mong Kok pedestrian street culture before it faded with the de-pedestrianization policy. This zone has been a significant landmark to both locals and tourists – not only does it provide the seedbed for local culture, it also reflects the development, changes and stories of Hong Kong.

Figure 1. A night view of Fa Yuen Street (花園街 ), Mong Kok (Photo by Chi Lok TSANG/ CC BY 3.0)

1. Introduction

Located at the centre of Kowloon Peninsula, Mong Kok has long been a place with seemingly conflicting traces. First, it has been a crux of local culture – gathering local shops (hawkers, street food, niche stores for youngsters), local people and tourists in seek of the authentic side of Hong Kong. It is visited in the highest frequency by tourists and locals as a cultural and leisure centre respectively. It is known for its chaotic, bottom-up spirit. Second, and a phenomenon that gains momentum later, Mong Kok lies at the centre of the MTR network and serves as the transfer station for two major metro lines. It represents a homogenizing force, with its orderliness and its role as a driver of large-scale urban development. This project examines the juxtaposition of these two forces in general, and in particular whether the MTR’s dominating influence has affected local culture and whether there is any conflict between these contrasting traces.

2. A Cultural Geographical Perspective on Mong Kok

Our investigation is structured around the following question: Will the MTR, as one of Hong Kong’s key drivers of urbanization, eradicate the local culture embedded in Mong Kok?

To reveal the relationship between daily commute and spatial arrangements of Mong Kok, Lefebvre’s spatial triad is used as a theoretical perspective to analyze how the space in Mong Kok interact with the culture there, and contribute, if any, to the existing culture.

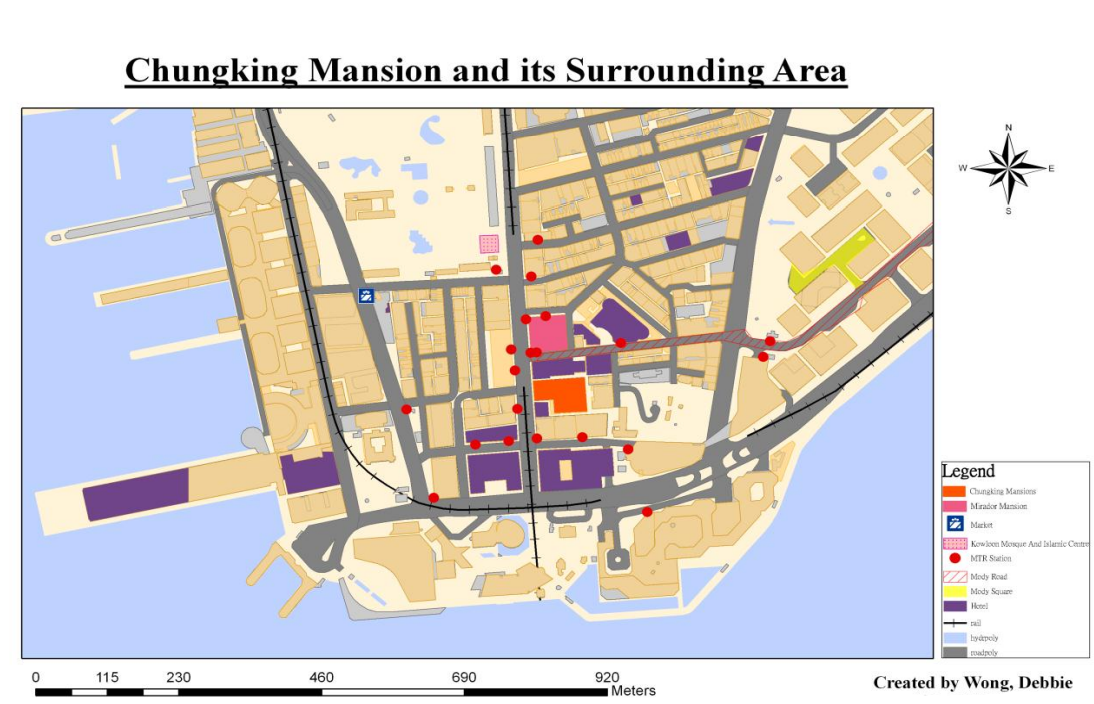

Lefebvre’s spatial triad consists of three elements:

- Representation of space is the conceived space by the ones in power in influencing the city plans and urban planning, e.g. scientists and planners;

- Representational space is the consumption of space by daily users, e.g. using the space according to personal feelings, intuition, and habits.

- Spatial practice is the daily usage of space on which we implement our knowledge

Figure 2. An illustration of Lefebvre’s spatial triad (Source: Lefebvre, 1991)

The spatial triad provides a way to analyze how space is both a tool and a result of the power struggle between social groups with different levels of power. It draws attention to (A) how users of stronger or weaker power conceive the places based on their daily routines and habits, and (B) how the conception of spaces by daily users reshape the conception of space by urban planners. Specifically, we argue that the complicated, fast-paced urban spatial arrangement in Mong Kok – i.e. the representation of space developed by the MTR – has limited the growth of the local culture.

3. Empirical Analysis

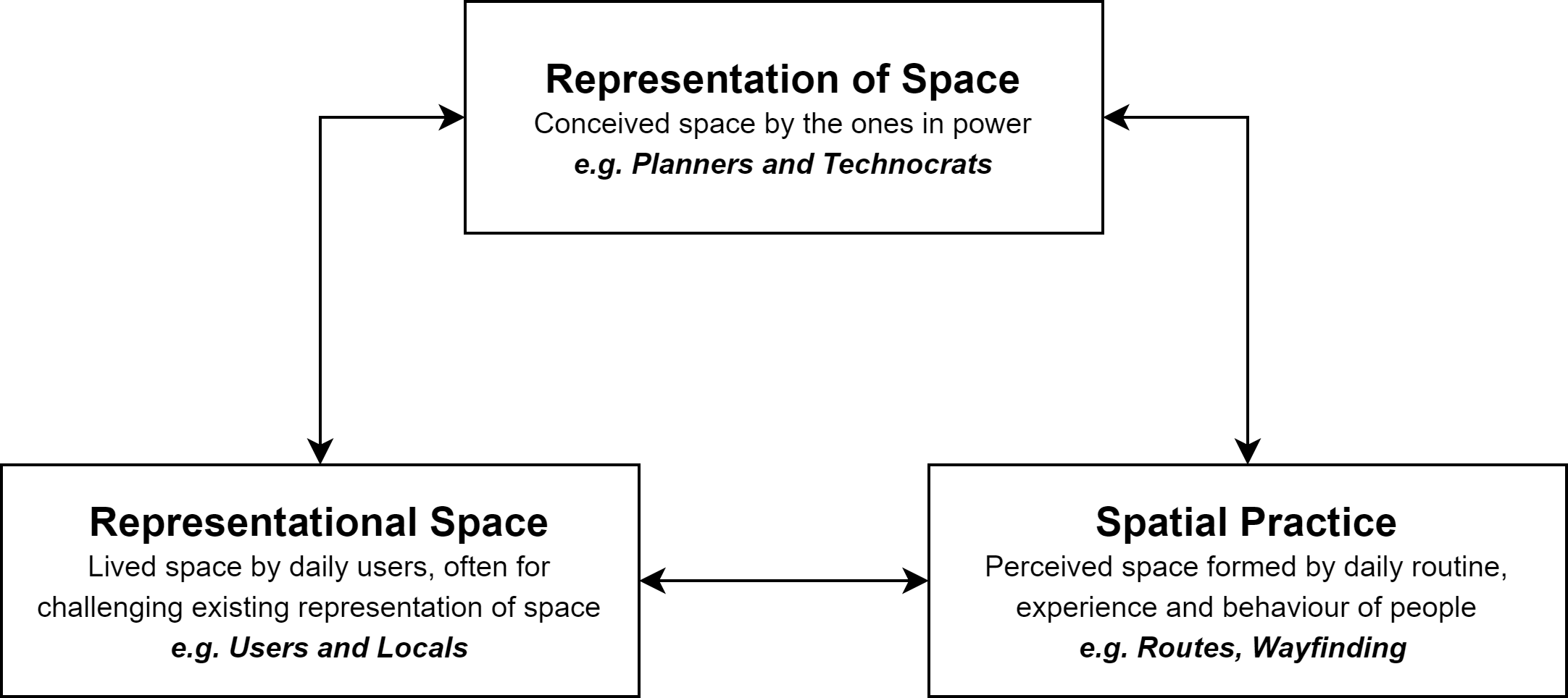

Representational space and representation of space in Mong Kok: Impacts of the MTR

Once a farming village, Mong Kok began to flourish at the beginning of the 20th century as a commercial area. It has since evolved into a melting pot of ‘street culture’, a set of ‘practices, styles, symbols, and values associated with, adopted by, and engaged in by individuals and organizations that spend a disproportionate amount of time on the streets of large urban centres’ (Ross, 2018, p. 8). It is known for its open-air markets, where locals and tourists alike visit the hawkers for knockoffs and street food. It is also known for its appeal to teenagers, who patronize the area for its concentration of entertainment venues, electronics stores and vendors of trendy products. It is furthermore known for its pedestrian zone, whose success in attracting a large number of street performers provoked local residents’ opposition that led to its abolition.

The chaos and crowdedness bolstered by these diverse traces of culture stand in sharp contrast to the orderliness brought by the MTR. As Hong Kong’s railway monopoly, the MTR structured the culture of Mong Kok and other parts of the city through its extensive railway network. With the power to enforce a set of by-laws on any railway premises, the MTR has transformed wherever its railway reaches into spaces with ordered cultures. As a notable example, the MTR stations are full of instructions – from exits, directories, the flow of people, where to stop and where not to etc., from eye level, above and below, with none that was left with no regulatory guide. These signs were accompanied by non-stop announcements, from reminders of last trains and safe use of elevators, to appeals for passengers to squeeze into the carriages to make room for others.

Owing to the dominance of cultural values embedded by the MTR development, these geographical borders further extended beyond the metro stations and infiltrated various streets and landmarks. Signs and guides for metro stations and exits are ubiquitous in the public spaces including various pedestrian walkways, flyovers and shopping centres.

Figure 3. The MTR stations in Mong Kong are highly regulated spaces.

Evidence of transformation: Spatial practice in wayfinding and navigation

An emerging trace in unveiling the impact of metro developments on spatial practices is the pedestrians’ changing sense of direction and wayfinding behaviours. Before the construction of the MTR station, most residents relied on landmarks and streets for navigation which represents the chaotic and yet disordered traces. The Mong Kok streetscape has undergone significant transformation and socialization. Since the 1970s, commercial activities have burgeoned and grown around nodes of the MTR stations given their high accessibility. Old buildings such as tonglau (唐樓) are hence gradually overhauled by office complexes and malls such as Langham Place, which become the new exits of the metro stations. The transformation of space has then marked the transition of value from disordered yet continuous space into socialized space advocating formality, orderliness and regularity.

These transformations in cultural traces are evidenced by the results of our street survey. The MTR exits have become the dominant trace which people depend upon for navigation. During our field study, 60.9% of our respondents use metro signs and exits to find their ways and destinations in Mong Kok. Some would identify the location of a place by its closest MTR exits. Some even deliberately move from one location of Mong Kok to another through the MTR station in order to orient themselves with the aid of the station map. At the same time, 84.5% of the respondents indicated that they were unable to identify the streets of Mong Kok without the aid of an MTR map. These findings suggest that most of the places in Mong Kok have been socialized by the values of orderliness and regularity introduced by the dominating power of metro stations. These transformations have, thereby, significantly reshaped the pedestrians’ conception of space and directions, as well as their behaviour in their navigation of Mong Kok.

These spatial practices are in contradistinction to those of the local inhabitants and daily users. Long-term residents inhabited for many years tend to rely more heavily on the street names than their non-residential counterpart, who can barely identify other parts of Mong Kok besides the town centre due to the crowdedness and disorganized culture of the streetscape. While youngsters tend to rely on metro signs and iconic, middle-aged and senior citizens roam around based on their knowledge and impressions on the streetscape. Owing to more established and complete memory of the urban areas, many residents can visualize Mong Kok by street names and even demolished buildings when compared to their younger counterparts. However, as the dominating metro culture continues to develop, it is expected that fewer and fewer pedestrians may perceive the space by buildings and streets, and hence vanish of the disorderliness of street cultures.

Figure 4. An illustration of Lefebvre’s spatial triad and the conflicts between street and metro culture in Mong Kok

This finding suggests that the formation of new and organized cultural traces as facilitated by the MTR development has significantly altered people’s conception and knowledge of a space and how they navigate. These metro culture has been acting as a dominant force that reshaped and socialized the streetscape in Mong Kok. These findings generally correlate with Lefebvre’s idea of the spatial triad. While people in power may structure their representation of space through imagining Mong Kok into an organized city with full metro coverage and signs in various public spaces, other users may have their own values assigned to the landscape through representational space. Both of these traces are merged into the spatial practice through everyday routine and experience of wayfinding and navigation in Mong Kok.

4. Conclusion

This study attempts to integrate Lefebvre’s spatial triad into the examination of how railway developments significantly reshaped the distinct cultural practices in Mong Kok. While the spatial arrangements in Mong Kok are heavily regulated by organized yet dominant metro culture, pedestrians spatial practice and daily routine of navigations and wayfinding have also been socialized by the metro’s value of formality and regulation. However, the government and the MTR have not been all-powerful. The subcultural groups could respond with tactics through spatial reimagination and practices to counter the representation of space and values by the powers. For instance, re-imagining our own short-cuts and alternatives to the directions of the metro signs on skywalks may allow us to explore and experience Mong Kok in unconventional ways, thereby defying conventions embedded by metro cultures.

Reference

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Oxford: Blackwell.

Ross, J. I. (2018). Reframing urban street culture: Towards a dynamic and heuristic process model. City, Culture and Society, 15, 7-13. doi:10.1016/j.ccs.2018.05.003

This page is developed based on a project undertaken by students ... in 2018-19.

1. Introduction

Strolling on the streets in Keelung, one would be amazed by the cultural diversity which shapes the city’s distinctive local landscape. Located at Taiwan’s northern tip, Keelung has been one of the important gateways to Taiwan.

This research departs from the cultural geography perspective that a place is formed by cultural traces left by a series of conflicts and integration of cultures. In the case of Keelung, its cultural landscape is formed through the interplay of different prevailing socio-political forces during the reign of three governments:

- the Qing Court (1683–1895), under whose reign people from southern Fujian, also known as Minnan (閩南), migrated to Keelung;

- the Japanese colonial government (1895–1945), which took over Taiwan after Qing’s loss in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), and

- the Republic of China (ROC) government (since 1945), which acquired Taiwan’s sovereignty after Japan’s defeat in World War II.

Location of Keelung in Taiwan (Map by Luuva / CC BY-SA 3.0)

2. Cultural Geography Perspective in Use

From a cultural geography perspective, a place is formed by various cultural traces which reflect and reinforce a particular cultural order. Every place has its own cultural order, which is defined by the social groups possessing dominating power. The presence of cultural order means that some groups are accepted in a place, while others are marginalised, if not completely crowded out. Cultural traces in a place captures the outcome of the interaction between social groups, and their relative position in the cultural order. As such orders evolve over time, older cultural traces may be erased by, overlaid upon, or integrated with newer traces, creating a complex cultural landscape.

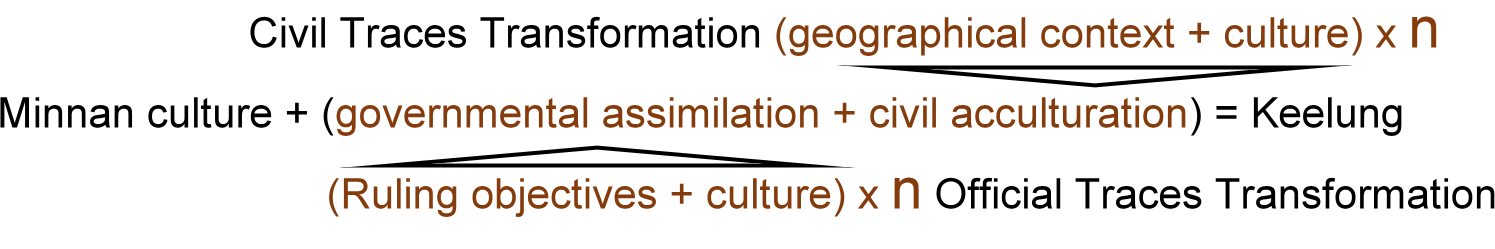

Keelung is a sum of Minnan, Japanese, and ROC culture, with the assimilation managed by the government and the acculturation promoted by citizens through conflicts and compromises. Governmental assimilations added new traces to erase the legacy of the last era and to propagate the dominant culture. In spite of the governmental unyielding changes, the public also encounter conflicts between different cultural beliefs when new culture entered Keelung. The clashes may result in a mixture of distinct beliefs after a period of time. Although new cultures were not accepted when they first entered Keelung, as time passes, people gradually integrate foreign cultures with their own culture, and that forms the modern Keelung.

Socio-political conflicts as well as traces of cultural integration can be observed throughout Keelung’s development since the 19th century. The following discussion will evaluate how a combination of Minnan, Japanese and ROC influences have given rise to three distinguishing features of Keelung: the city’s Ghost Festival, the spatial complex of Dianji Temple (奠濟宮) and Miaokou Night Market (廟口夜市), and the city centre’s road system.

3. Traces of Cultural Integration and Transformation

3.1 Keelung Ghost Festival

Keelung Ghost Festival is an intangible cultural trace of the armed conflicts between migrants from different parts of Minnan, a region separated from Taiwan by the Taiwan Strait. During the Qing Dynasty, many Minnan people migrated to Taiwan in seek of a better life, with Keelung being one of their popular destinations. These people came mainly from two parts of Minnan, Zhangzhou (漳州) and Quanzhou (泉州). Due to their different origins, religions and cultural practices, these new settlers ran into a series of deadly confrontations during the 1850s, now collectively known as Zhang-Quan Conflicts (漳泉械鬥) (Wei, 2011). The Zhangzhou people won and took over the land near Keelung Harbour (基隆港), while the Quanzhou people were forced to move inland to Nuannuan District (暖暖區).

District map of Keelung City, Taiwan (Adapted from: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b1/Keelung_districts_map.svg)

To avoid further bloodsheds, leaders of the Zhangzhou and Quanzhou migrants eventually reconciled in an interesting manner. Instead of physical confrontations, they agreed that their communities would compete in hosting rituals during the Chinese Ghost Festival, which falls on the 15th day of the seventh month of the Chinese calendar, to appease and sate the deceased (Wu, 2009). The competition, represented at first by 11 and later 15 clans, continues to date in two parts. First, the clans compete across years as they take turn to decorate the main alter (主普壇) of the year as elaborately as possible. Second, the clans also compete head to head in the same year in organising the most eye-catching street parade. Given its colourfulness, Keelung’s Ghost Festival attracts a lot of local visitors and foreign tourists, and earns the name of one of Taiwan’s top twelve festivals identified by the Taiwan Tourism Bureau.

The three-storey main altar of Keelung Ghost Festival, currently used as the Keelung Mid-summer Ghost Festival Museum

(Photo by Eugene Yeh / Photo courtesy Taiwan Tourism Bureau)

3.2 Dianji Temple and Miaokou Night Market

The history of Minnan migrants also leaves a tangible trace in Keelung – Dianji Temple, whose siting reflects the legacy of Zhang-Quan conflicts. Established in 1875, Dianji Temple was built by the Zhangzhou community to worship the Sage King Kaizhang (開漳聖王), a Minnan folklore hero, for his loyalty and effort in developing the Fujian province (Keelung Municipal Government, 2018). At the back of Dianji Temple lies Qingning Temple (清甯宮), built by the Quanzhou community to worship the Gods of the Water (水仙尊王). Since Quanzhou people lost in the conflicts with Zhangzhou people, they were only qualified to build their temple as a smaller building behind Dianji Temple.

Keelung Dianji Temple (Photo by lienyuan lee / CC BY 3.0)

In addition, Dianji Temple showcases the compromise and coexistence of Japanese and Chinese cultures. The temple’s main hall stands two pairs of pillars decorated with different motifs. Erected by the Japanese colonial government, the older pair is decorated with patterns of flowers and birds, as they are symbols of good fortunes and a free spirit in Japanese culture (Chen, 2005). On the contrary, added by the ROC government, the younger pair is decorated with patterns of a Chinese dragon, reinforcing traditional Chinese culture in the temple.

Pillar with pattern of a dragon in Dianji Temple. (Photo by yeowatzup / CC BY-2.0)

The significance of Dianji Temple has evolved over time with the development of Miaokou Night Market around it. In the past, countless people visited Dianji Temple for worships. This attracted many vendors to operate around the temple. The night market so formed is named ‘Miaokou’, which literally means the entrance to a temple. However, in modern days, people are less superstitious and visit Dianji Temple as tourists instead of disciples. Therefore, the temple’s social significance as a worship venue is gradually decreasing, while people pay more attention to the night market, particularly the wide range of food it offers, including those of Japanese, Minnan, Zhejiang, and Taiwanese origins. Miaokou Night Market has taken over the status of Dianji Temple as the most important spatial feature of the local area at which they are located.

Miaokou night market (Photo by Wu-Chih Hsueh / Photo courtesy Taiwan Tourism Bureau)

3.3 Keelung’s Road System

The road system of Keelung is a typical example of spatial transformation for economic and political goals. The system first took shape during the Japanese colonial era, when the colonial government considered Keelung a place with great development potential but physically in disorder. To develop Keelung into a modern port city, the colonial government formulated the Keelung Municipal Improvement Plan in 1905. The plan introduced a grid of modern roads and sewers to facilitate modern transport and reduce flooding risk (Ho, 2018).

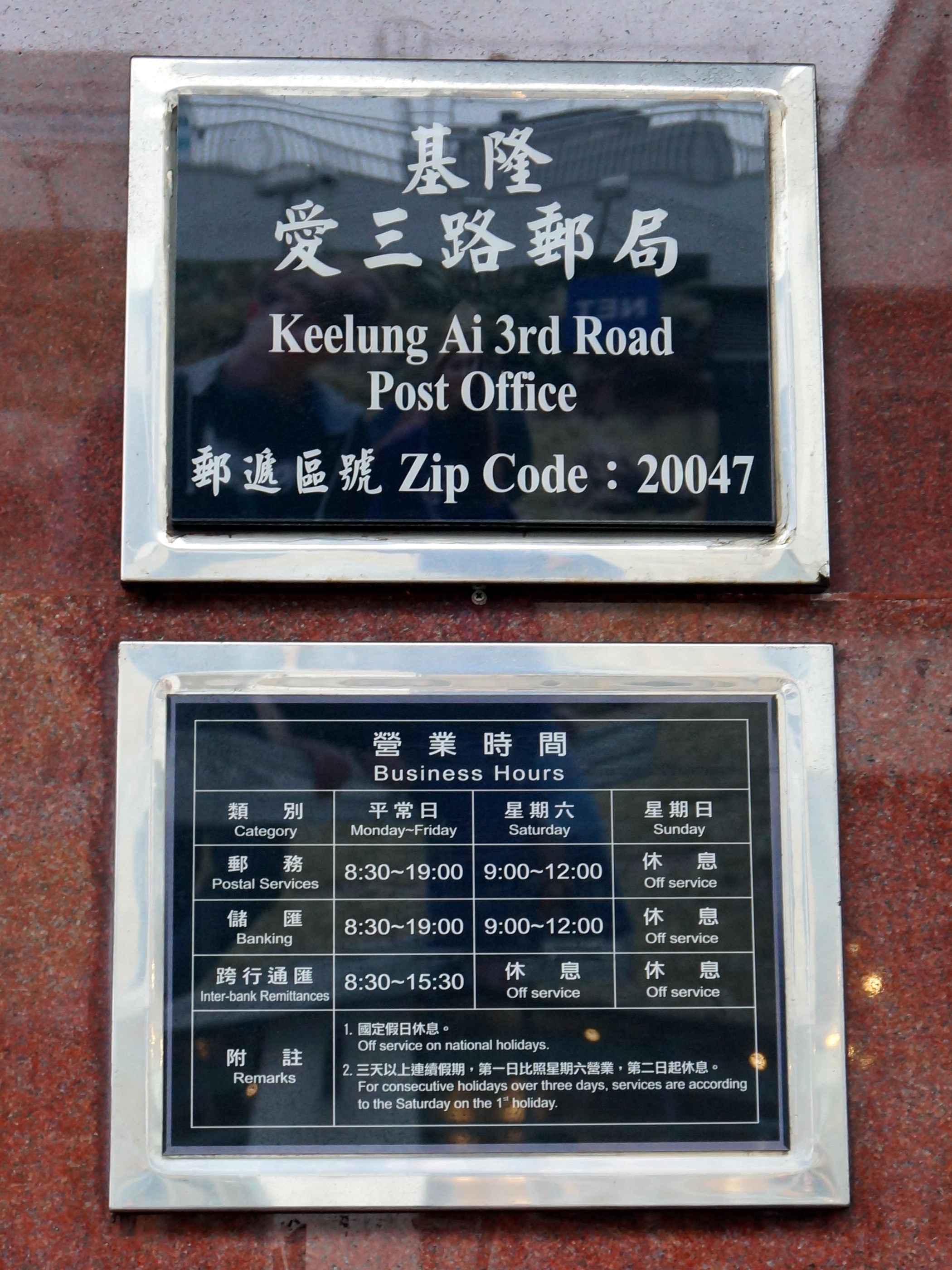

Keelung’s grid road plan, 1945 (Map by U.S. Army Map Service / Courtesy University of Texas Libraries)

After World War II, the ROC government was eager to erase Japan’s colonial influence and assert its authority on the island. In Keelung, the ROC government preserved the grid of roads, but renamed them according to the ‘eight virtues’ generalised by Sun Yat-sen, the founder of ROC, from traditional Chinese values (Lee, 2016). They include dedication (忠, zhong), filial piety (孝, xiao), benevolence (仁, ren), love (愛, ai), trustworthiness (信, xin), justice (義, yi), peace (和, he) and equality (平, ping).

Keelung’s roads named after eight virtues: Ai 3rd Road (left) and Xin 2nd Road (right)

(Left and right photos by Solomon203 / CC BY-SA-4.0)

4. Concluding Thoughts

Owing to conflicts and compromises among the Minnan migrants and the ruling powers in the past hundred years, Keelung, a small city at the top of Taiwan’s map, bolsters a range of material and non-material traces which embody the cultural influences from the Minnan communities, the Japanese colonisers, and the officials of the ROC government. From these mesmerizing and intriguing traces, we can retrace and study how dominating powers and transgression of different parties shape the cultural diversity and distinctive cultural landscape of the city over time.

Roses always come with thorns. Foreign cultures, while giving birth to Keelung’s cultural diversity in the past, may dampen its cultural diversity nowadays. Under the influence of globalization, local cultures are at risk of being banished. In recent decades, the local government developed the cruise economy in Keelung port, driving up land rent in Keelung. Some local vendors cannot afford the rising cost and have been displaced by stores of multinational corporations with stronger financial strength. Without concerted effort to conserve the local ways of living, Keelung’s cultural diversity and continuity may cease to exist. Whether Keelung can preserve its uniqueness in cultural terms is a question that deserves our further attention.

References

Keelung City Government.

(2018). Keelung Travel - Dianji Temple. Retrieved from https://tour.klcg.gov.tw/en/attractions/temples/奠濟宮/

Wei, L. (2011). Chinese

festivals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wu, H. (2009). Kinship

Resolution to Replace Regional Conflicts? The Ghost Festival in Keelung and the

Surname Rotation System. The Journal of History, NCCU, (31), 51-95.

何昱泓(2018年09月21日)。〈鍵盤基隆小旅行:從築港工程到地下旭川,百年來港都大改造的歷史軌跡〉。取自https://gushi.tw/old-times-keelung/

李筱峰(2016年03月08日)。〈基隆地名的故事〉。取自http://www.peoplenews.tw/news/878a496e-49b2-4456-b38a-0ac52e66d532

陳凱雯(2005)。〈帝國玄關─日治時期基隆的都市化與地方社會〉(碩士論文)。取自http://ir.lib.ncu.edu.tw:88/thesis/view_etd.asp?URN=91125015

Since the content of this module is test text, the final version of the text provided by you has not yet been obtained, the meaningless text is temporarily filled in to simulate the expected effect of future web site production.

| Student Sample #1 |

Student Sample #6 |

Student Sample #7 |

Student Sample #8 |

Student Sample #9 |

|

Student Sample #2 |

|

|

|

|

|

Student Sample #3 |

|

|

|

|

|

Student Sample #4 |

|

|

|

|

|

Student Sample #5 |

|

|

|

|