The Place of Politics

Introduction

Situated at the heart of the country, Beijing represents more than just the geopolitical centre of the Chinese regime, but also a longstanding historical origin and a melting pot of multi-ethnic cultures. As much as any other developments, the rise of Beijing as the capital city and a cultural hub for "Jinpai" (京派) and New Beijing culture has significantly transformed the city's landscape where these changes are strongly associated with its geographical context. In the following, we seek to understand why Beijing was chosen as the capital city and how it is related to Beijing's distinct cultural traces and practices.The Making of a Capital City

The capital city, as described by Spate (1942), can be interpreted as a physical manifestation of the power of the state and, though not invariably, the cultural pole of the country. Geographical forces that configured and altered the course of cultural-political history are hence expressed intensively in the development of the capital city and are evidenced by both material and non-material traces. In no case is the complexity of factors regulating the selection of capital city more distinctly represented in that of Beijing metropolis. Despite its poor geographical settings away from the southern region and inaccessibility to the coastal areas and natural resources, Beijing has still been designated as the geopolitical centre since the Yuan dynasty due to various intricate political, military, and economic concerns.

Since the Ming dynasty, the expansion of national territory into Mongolia, Tibet and Manchuria has been as one of its offshoots the deposition of Beijing – a crucial gateway where the earlier invaders had dominated the Chinese empire (Spate, 1942). Its strategic location in the northern plain, thereby, enables the containment of threats from the Russian and other invaders along the northern borders. The relative proximity of Beijing to Manchuria, Mongolia and Tibet also played an essential role in maintaining friendly relationships with their local leaders for consolidation of the political power (Barmé, 2012).

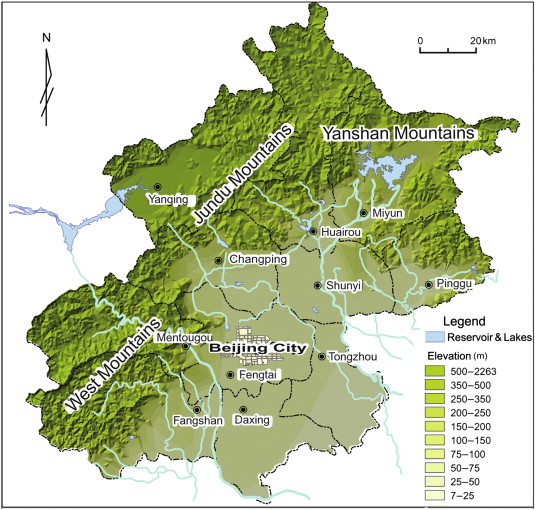

A topographic map of Beijing and its surrounding area

Reprinted from "Upgrading a regional groundwater level monitoring network for Beijing Plain, China", Zhou, Dong, Liu & Li, 2013, Geoscience Frontiers, 4(1), p.127-138

Beijing's distinct geomorphology, including mountain ranges as well as the Liaoning and the Shandong Peninsula, acts as a natural barrier to protect the city from foreign invasions. The rugged topography at Yanshan Mountains (燕山山脈), coupled with the Great Wall of China, provides natural defences against the armed forces of Mongolia along the northern borders (Chang & Liang, 2013). Despite attempts in restoring other cities, such as Nanjing, as the capital after the 1911 Revolution, their geopolitical locations were far inferior to Beijing owing to their vulnerability to foreign invasions and bombardment. The Japanese occupation in the 1930-40s, for example, reflected the problems of Nanjing and hence urging the state to relocate the capital city back to Beijing after the communist revolution in 1949. Therefore, owing to these geographical advantages of locating capital in the north in terms of uniting power and national security, Beijing was designed to be the geopolitical centre of China for many decades.

The Old Beijing culture: Traces of Imperiality and Hierarchy

Owing to the longstanding imperial and capital status, the Old Beijing city was constructed to represent not only the secular imperiality and authority but also the centre of the kingdom (Hershkovitz, 1993). As Wheatley (1971) described, "(Beijing represents) the point of ontological transition at which divine power entered the world and diffused outwards through the kingdom" (p.434). Hence, the city was carefully planned to resemble cosmographic principles according to the orthodox Chinese beliefs and rituals which benefit the consolidation of political power (Hershkovitz, 1993). Feudal ideas such as social hierarchy, centrality and male supremacy, which originated from the traditional Chinese philosophy of Confucianism and Taoism, were also expressed prominently and morphologically in the Old Beijing landscape. These transformations have constituted a significant influence on the urban landscape since the Ming dynasty and can be represented by the architectural styles of the Forbidden City (紫禁城) and siheyuan (四合院) – the homes for royal families and commoners respectively.

A Hu Tung (Old Beijing Lane) in Beijing (Photo by zhang kaiyv/ CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Forbidden City: Imperiality, Centrality and Hierarchy

Functioning as the political and ritual centre of China for more than 500 years, the Forbidden City offers a great glimpse into how these traditional values of imperiality, centrality and hierarchy were morphologically expressed in the heart of the capital city. Spatial hierarchy and centrality were closely represented in the spatial design and organization of the Old Beijing city and the palace. These constructions strictly followed the hierarchy ranks advocated in feudalism and Confucianism regarding the emperor as the highest position in the social hierarchy. The palace was rectangular in shape and was enclosed by cardinal walls and a south-facing gate known as Tiananmen. Within the palace, the Hall of Supreme Harmony (太和殿), the Hall of Central Harmony (中和殿), and the Hall of Preserved Harmony (保和殿) were constructed along the central axis and divided the palace into boxes of "outer court" and the "inner court". Outside the palace was another rectangularly walled district enclosing the entire palace called the "inner city". This complex boxes-in-a-box model delimits the ideas of spatial hierarchy and centrality as well as the solemn and majestic role of the emperor (Barmé, 2012; Hershkovitz, 1993).

A bird's eye view of the Forbidden City (Photo by Danny History & Ancient Cash Coin on Pinterest/ CC BY-SA 3.0)

The hierarchical ordering of space in Tiananmen also emblematizes the organization of political power of the regime. Tiananmen, the southern ceremonial passageway to the imperial palace, was closely accentuated by a series of watchtowers and guards. South of the gate was a T-shaped walled open space. The centre of the open space was a covered walkway known as Thousand Step Galley "Qianbulang" functioning as the venue for inspecting papers from candidates in public examination Keju (Hershkovitz, 1993). Behind the walled open space were the offices for government officials. These constructions symbolized a continuum of spaces of a gradual decline of sacrality with distance from the centre (ibid.).

Siheyuan: Spatial hierarchy and Feng Shui

The "Old Beijing" traces are strongly influenced by the local customs and traditional Chinese values such as social hierarchy and feng shui (風水). These cultures can be exemplified by the architectural styles of siheyuan (四合院). People are greatly influenced by Confucian values, respecting the elderly and ancestors, and Taoism, believing in a cosmic force that governs everything. Therefore, houses are built orderly in a rectangular arrangement and around water well in the middle. Its layout manifests the difference in status and the idea of 'superiority of seniority' (長幼有序), where the closer in family relationships and the older are prioritized. Planting mulberry (桑椹樹) and pear trees (梨樹) in the siheyuan are also considered as taboo for Old Beijinger since they are homophonic to the word "death" (喪) and "separation" (離) ("Lao Beijing", n.d.). All these values originate from Confucius and Taoism, showing a dynamic relationship between people and space. This also explains the famous saying that "Beijing people constructed Siheyuan, and meanwhile, Siheyuan shaped the Beijing people" (北京人建造四合院,四合院塑造北京人).

The entrance of a siheyuan in Beijing (Photo by vnwayne fan/ CC BY-SA 3.0)

Post-communist revolution (1949) and transformation of New Beijing

The massive transformation of Old Beijing culture took place when the communist party seized power. While representing revolutionary ideologies and patriotic resistance to the imperialist rule, the communist regime was placed in a paradoxical position after their victory in the Chinese Civil War. Their rise in power challenged whether the historical monuments, such as the Forbidden City, Tiananmen and siheyuan, which emblematize the lingering hegemony of the Chinese imperial rule, could be retained in the New Beijing city (Hershkovitz, 1993). Transforming these conflicting tokenisms, therefore, was urgent and pivotal to the legitimization of the communist regime giving rise to a New Beijing culture since 1949 (Hou, 1986).

Tiananmen was first to be reimagined and reconciled according to the communist image and concepts of New Beijing and New China. The former "T"-shaped open space was cleared of trees and expanded into Tiananmen Square, which further articulates the new spatial centrality and legitimacy of communist rule by introducing the Great Hall of the People and the Museum of the Chinese Revolution to the western and eastern side of the area (Hou, 1986). The tokenism of historical exclusion and hierarchy, such as walls and gateways in the inner city, was dismantled for introducing ideas of openness and inclusiveness of the new regime. A massive portrait of Mao on top of the central gateway of Tiananmen was added to reinforce the transformation into New Beijing.

On the other hand, traditional Old Beijing rituals and values as represented by siheyuan had undergone major transformations under the influence of New Beijing movements. While socialist industrialization prevailed in the city, residential districts were often attached to workplaces to form work unit compounds. Many standardized nondescript low-rise apartments built were influenced by socialist planning theories which advocate equity and equality (Hui, 2013; Yan, 1990). Experimental neighbourhoods were also planned with a commune cafeteria instead of individual kitchens for each apartment to reinforce the communist ideologies of cohesiveness and collectivism (Yan, 1990). The upholding of socialist architectural symbolism in residential planning had significantly reshaped the old city's landscape while marginalizing the importance of heritage conservation and the Old Beijing culture (Wong, 2015; Yan, 1990).

Under such context, the "Liang-Cheng Proposal", which envisioned an urban future by redirecting economic development to newly expanded areas while preserving the vibes of the ancient city, was formulated to counter with state's attempts in redeveloping the old city. The idea, however, was rejected by the state due to its strong emphasis on western planning theories and contradictions with the socialist imaginations of the New Beijing city and New China (Wong, 2015). It was not until the 1990s that the legacies of Liang and Cheng are re-emphasized in the Chinese planning system as evidenced by a more sensitive approach in the planning to protect the city’s heritage.

Reference

Barmé, G. (2012). Forbidden city. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Chang, Z. Q., & Liang, Y. C. (2013). Cong lishi dili de hongguan mailuo kan zhongguo yu beijing ─ guanyu gudu wenhua de duihua. Wenhua zhongguo, 77(2), 4-14.

Hershkovitz, L. (1993). Tiananmen Square and the Politics of Place. Political Geography, 12(5), 395-420. doi:10.1016/0962-6298(93)90010-5

Hou, R. (1986). The transformation of the old city of Beijing, China. In M. P. Conzen (Eds.), World Patterns of Modem Urban Change (pp. 217-239). Chicago: University of Chicago, Department of Geography.

Hui, X. (2017). Housing, Urban Renewal and Socio-Spatial Integration. A Study on Rehabilitating the Former Socialistic Public Housing Areas in Beijing. A BE (Delft.), (2), 1-796.

Lao Beijing. (n.d.). Retrieved August 03, 2020, from https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E8%80%81%E5%8C%97%E4%BA%AC/8388502?fr=aladdin [Lao Bei Jing. (n.d.).]

Ouroussoff, N. (2008, July 23). Lost in the new Beijing: The old neighborhood. Retrieved August 03, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/23/arts/23iht-27ouro.14711541.html

Spate, O. H. (1942). Factors in the Development of Capital Cities. Geographical Review, 32(4), 622. doi:10.2307/210000

The Forbidden City, China. (n.d.). Retrieved August 03, 2020, from https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/south-east-se-asia/china-art/a/forbidden-city

Wheatley, P. (1971). The Pivot of the Four Quarters: A Preliminary Enquiry into the origins and Character of the Ancient Chinese City. Edinburgh: Edmburgh University Press.

Wong, S. (2015). Searching for a modern, humanistic planning model in China-The planning ideas of Liang Sicheng, 1930-1952. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 32(4), 324-345.

Yan, X. Y. (1990). Human impacts of changing city form: a case study of Beijing [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Michigan]. Dissertation Abstracts International 51-04A.

Zhou, Y., Dong, D., Liu, J., & Li, W. (2013). Upgrading a regional groundwater level monitoring network for Beijing Plain, China. Geoscience Frontiers, 4(1), 127-138. doi:10.1016/j.gsf.2012.03.008