Introduction

Graffiti has always been framed as vandalizing and by-law contravention of public space worldwide. Despite its nature of unauthorized writing and drawing, it represents more than just chaotic messes but cultural traces of youth culture, borders, and politics of space. Before discussing the cultural geographies of graffiti, let us understand the reasons behind their daredevil pursuits and hence, how borders and politics of space regulate these cultures.

A Graffiti found in Bristol, United Kingdom (Photo by Mec Rawlings/ CC BY-SA 3.0)

Graffiti and Border: A Space for Youth and Artists?

Historically, people have been frequently categorized into various social classes based on their different parameters, such as age group, races, or socio-economic status. For instance, age categorization is often used to label adults who are capable of driving or purchasing alcoholic beverages. While these conventional bordering mechanisms are often utilized for immediate labelling of people for various purposes, these classifications may create “grey areas” for people not aligning with the ordered mainstream culture (Anderson, 2010).

Youngsters, particularly, occupy ambiguous positions in the social spectrum being bordered outside the public space naturalized as either adult or child (ibid). These areas and public space, such as playgrounds and pubs for adults and children respectively, cater only passive recreation without space for the energetic youth. While age classifications are useful for differentiating individuals requiring supervision or could be morally or legally responsible for their behaviours, classes outside of the conventional borders, such as the youth, elderly or middle-aged, may not be able to find their positions in society (ibid). Turner (1982), hence, described these youngsters as “liminal beings” due to their undermined and marginal positions between the conventional distinctions of “adult” and “child”.

Imagine if you were a high-school student and you want to find somewhere to hang out with your friends or even to voice out your opinions about the current socio-political debates, where would you go? You are clearly over-aged for the playground while under-aged for most bars and pubs. Although you seem more thoughtful than your childhood self, your opinions are still undermined in the traditional social hierarchy as you are not “mature” enough to be an adult and make the “right” judgements or observations. What could you do to (re)claim your space? That is right: create your own.

There is where the notion of street and graffiti comes into place. As described by Anderson (2010), “street” refers not only to the sidewalks or streetscape but all public outdoor places that enable the celebration of individualism and expression of emotions of youngsters. These spaces are not regulated in an authoritarian way with strict rules and constant monitoring. They are not bounded by the adultized mainstream cultures and open for transgressive uses making them as “temporary autonomous zone” for youth.

A Graffiti found in Hong Kong Island (Photo by Richin Chin)

Whilst graffiti is a means for the youth to carve out space for them and establish their stake in the society in a world congested with borders which do not fit them , artists, on the other hand, may also be marginalized by these mainstream cultures. Very often, artists are avant-garde. Their works are experimental, radical, or unorthodox. Thus, they may be excluded by prominent and mainstream ideologies and cultures.

Graffiti, Space and Politics

Graffiti itself does not necessarily be related to political arguments, yet its spatial and temporal extensions are politically charged and infused. As Nandrea (1999) articulated, one of the key functions of graffiti is “to stake out gang territory, to lay claim to an alley, a corner, or an entire area symbolically fenced off by gang signatures”. Therefore, graffiti embodied the construction of new borders and ownership of space explicitly for teens and other undermined social classes as a challenge to the adultized or other mainstream cultures and laws questioning “whose place is this”? (Anderson, 2010). These proclamations may then trigger immediate responses from the state for reinforcement of their power in space through laws and regulations. This case symbolizes the idea of politics of space – the dynamic and struggle of power between the state and the public.

One example of the idea and the dynamic power relations is the current trend of commodification and institutionalization of graffiti and street culture. Commodification refers to the making of money out of graffiti as a commodity while institutionalization refers to the formal rules that regulate how graffiti is created. Graffiti, as argued by Nandrea (1999), has been reconfigured and assimilated into the mainstream culture under the capitalist realm through dismantling traces of youth and other subcultures. The “street”, is thereby, transformed into “High Street”, as space where business prospers and mainstream capitalist values exhibited while removing the threat, transgression and non-commodifying nature possessed by the street culture (Anderson, 2010; Cresswell, 1996). The contemporary trend has also provoked debates on whether the commodified graffiti violate its nature for expression of opinions and emotions of youth and other bordered groups.

The concepts of power struggle and cultural commodification in street culture can best be illustrated by the 798 Art Zone Case in Beijing and the Hong Kong Graffiti Development.

Commodification in Progress: the 798 Art District

What is the 798 Art Zone?

Located in Beijing, the 798 Art District symbolized the state’s attempt into the rhetoric glorifying of the creative industries while commodifying the street culture and graffiti. The 798 originated as a state-owned factory complex for electronics and weapons production and had been almost empty after most industries were relocated since the 1980s. The artists have then transformed the old industrial areas and reinvigorated the area into a cultural and artistic enclave with innovative and young vibes from young artists of various backgrounds (Currier, 2008). While encouraging cross-cultural collaborations and explicit expressions of creativity through graffiti, architecture and artefacts, it has since then debuted and shined at the international stage as a celebration of creativity (Brunner, 2017).

Graffiti found in 798 Art Zone (Photo by Calvin Chung)

Struggle and competition of street and mainstream culture

The 798 Art Zone illustrates the relic of the power struggle between the marginalized classes of youth and artists with the mainstream culture for public consumption during its course of development and two phases of transformations (Zhang, 2012).

The first wave of transition is configured by the rapid transformation from a vacant industrial area to the art zone by bordered and marginal communities (mostly young artists). Being suppressed by the conventional age categorization and capitalist profit-making culture, the youngsters and artists gathered around the area and established their studios with cheap rent and ample working space at only 0.3 yuan per day (Dekker, 2011). Free and bold expressions of emotions, opinions and moaning of cultural suppressions were exemplified through various graffiti and artworks in the zone. Strong social bonds and sense of community have also been developed due to their empathic connections with one another under such context (Currier, 2008).

The resistance of the marginalized groups to dominant cultures through street culture had, indeed, caught attentions from the state. Deeming the marginalized groups as potential risks, the government intervened and prohibited its development through collaborations with landlord and the owner of 798 - the Seven Stars company, for destroying posters in exhibitions and preventing taxi from entering the zone. These responses from the state and market, had, however, raised international attention describing the area as “hotspot for modern Chinese arts” and initiated the second wave of transition – from 798 Art Zone to tourist destinations (Waibel & Zielke, 2012). The state has, since then, closely collaborated with the market and attempted to commodify and incorporate street culture back to mainstream culture for both tourist and public consumption in a non-transgressive and non-threatening way.

The second wave of street culture institutionalization has then elicited widespread debates from scholars and media questioning the nature of street culture. First, strict laws regulating the scope of public debates on socio-political issues undermine the freedom of expression of youngsters and artists (Brunner, 2017; Zhang, 2012). Graffiti and other artworks were not allowed to express criticism for the communist regime, thus resulting in political self-censorship among artists (Brunner, 2017). Second, the creative industry has also been heavily regulated and influenced by capitalist systems. Most elements of street cultures are now only produced because market demand exists instead of the expression of emotions or creativity. Some artwork is excessively expensive, which deconstruct the connections of street culture with the expression of opinions from marginalized groups (Brunner, 2017; Branigan, 2010). A lot of artists and youngsters have to leave due to the increased land rent in the area (Branigan, 2010).

Graffiti and Politics of Space: A Tale of the “King of Kowloon”

Who is the "King of Kowloon"?

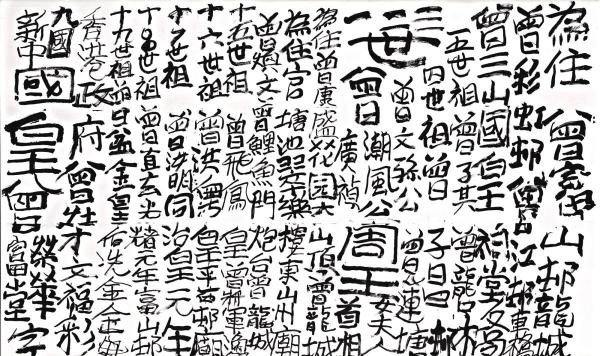

The case of Hong Kong and the “King of Kowloon” also offer some great insights into the discussion of graffiti commodification. Tsang Tsou-Choi (1921-2007) is one of the most renowned artists and pioneer in popularizing urban street culture and graffiti in Hong Kong. Proclaiming himself as the “King of Kowloon”, Tsang’s work is considered as one of the “collective memories” and a crucial part of Hong Kong culture (Valjakka, 2016). His practice was provoked by his infuriation to the British colonial government for failing to recognize the rightfulness of the land and his title in the Kowloon peninsula. Despite multiple attempts in expressing his resentment, his claims were dismissed by the government due to the lack of evidence (Chang & Gao, 2012). Thus, Tsang began to mark his royal patents and decrees on the street with a mixture of black ink and paint. As a result, he was regarded as rather a calligrapher than a graffiti artist (Valjakka, 2016).

Traces of the "King of Kowloon" (Photo retrieved from Orange News/ CC BY 2.0)

From lampposts to Converse shoes: Responses from the government and the market

Tsang’s graffiti represents the cultural traces of the power struggle between dominant and marginalized classes. Owing to the illegal nature of his work, he was in frequent confrontations with the government authorities and was arrested and detained numerous times. His work was also erased wherever the police found them. Despite facing suppression from the dominant powers, Tsang continued to express his anger through calligraphy and graffiti in various places on the street ranging from lampposts, pillars and walls to cars and even other private properties. However, the government responded softly towards his repeated flagrant violation of laws and ignorance of warnings as he was rarely charged for vandalism. His graffiti can thus, as described by Chang & Gao (2012), be regarded as the “reclaiming of public space” and the accusation of state incompetence.

However, the contextual meaning of his graffiti changed significantly in recent years (Valjakka, 2016). His relentless attempts into reapplying and re-publicizing his proclaim through graffiti gained international attention from many different artists. For instance, one of his work was sold for USD$7050 in October 2004. His work is also being considered as “a signifier of a local” (Clarket, 2001, p.183). Recognizing the commercial value and importance in local identity building, both the market and the state have since then drawn attention to his work. Shortly after his death, his last surviving work in public space was acquired by the M+ museum in West Kowloon, while another one in Tsim Sha Tsui Pier was protected by plexiglass.

Nonetheless, neither of these attempts were made solely for the commemoration of Tsang’s work. Many of his work was then commodified and re-employed as souvenirs ranging from posters, stationery, mugs to even Converse shoes (“Who is the King of Kowloon?”, 2011). Started as an expression of displeasure to the government, his work has then been taken out of context and have gradually lost its colours (Ho, 2014). The commodification of his “graffiti” has then erased and neglected the core values of street culture as a representation of voices from the suppressed and marginalized.

Summary

Graffiti and street culture illustrate the key concept of borders in cultural geography. Conventional categorization of individuals may create borders for marginalized classes and culture such as youngsters, who belong neither to “adult” nor “child”. These mainstream cultures have then marginalized the youth and drive them to establish their presence through street culture. The struggle of power between mainstream and marginal classes may also (re)shape the spatial extensions of other bordered cultures. While we are often concerned with whether the value of graffiti as a street culture may be undermined by its commodification or institutionalization, this page takes a step back to consider why graffiti would be created in the first place. Graffiti can be a sign that some social groups or people feel that they are underrepresented in the mainstream culture – they resort to graffiti as a means to counteract the mainstream, or to de-border. With this understanding in mind, a more important question for us to consider is how the demands from the graffiti-makers can be addressed.

Reference

Anderson, J. (2010). Understanding cultural geography: places and traces. Routledge.

Branigan, T. (2010, February 24). Beijing artists say development is driving them out. Retrieved July 14, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/feb/24/beijing-chinese-artists-studios-evictions

Brunner, E. (2017). Imagining China through the culture industries: The 798 art zone and new Chinas. In Imagining China: Rhetorics of Nationalism in an Age of Globalization (pp. 339-369). Michigan State University Press.

Chang, Z., & Gao, C. (2016). Graffiti Hong Kong: Public space, politics and globalization. Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong Press.

Clarke, D. (2001). Hong Kong Art. Culture and Decolonization. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Cresswell, T. (1996). In place/out of place: Geography, ideology, and transgression. Minneapolis, Mn.: University of Minnesota Press.

Currier (2008). Art and power in the new China An exploration of Beijing’s 798 district and its implications for contemporary urbanism. Town and Planning Review, 79 (2/3), 237-265.

Dekker, R. (2011). 798 ART ZONE BEIJING Site of ‘Cultural Revolution’ or Showpiece of City Marketing?

Nandrea, L. (1999). Graffiti Taught Me Everything I Know About Space’: Urban Fronts and Borders. Antipode, 31(1), pp. 110–116., doi:10.1111/1467-8330.00094.

Turner, V. (1982). From ritual to theatre: The human seriousness at play. New York: Performing Arts Journal

Valjakka, M. (2016). Contesting transcultural trends. Emerging self-identities and urban art images in Hong Kong. In Routledge handbook of graffiti and street art. London: Routledge.

Who is the King of Kowloon? ArtisTree exhibition pays tribute to artist and eccentric Tsang Tsou-choi. (2011, April 05). Retrieved July 14, 2020, from https://artradarjournal.com/2011/05/04/who-is-the-king-of-kowloon-artistree-exhibition-pays-tribute-to-artist-and-eccentric-tsang-tsou-choi/

Zhang, Y. (2012). 艺术・商业・政治: 北京798艺术区的前世今生 [Master of Philosophy dissertation, Chinese University of Hong Kong]. Retrieved from: https://repository.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/tc/item/cuhk-328441