A Study of Mong Kok’s evolving spaces through Lefebvre’s spatial triad

Foreword

The research project pays homage to the street culture of Mong Kok pedestrian zone, which has been permanently closed down on 31 August 2018 due to overwhelming noise pollution. This research project was conducted from September to December 2017, shortly before its closure. It is believed that the project could show the glimpse of Mong Kok pedestrian street culture before it faded with the de-pedestrianization policy. This zone has been a significant landmark to both locals and tourists – not only does it provide the seedbed for local culture, it also reflects the development, changes and stories of Hong Kong.

Figure 1. A night view of Fa Yuen Street (花園街 ), Mong Kok (Photo by Chi Lok TSANG/ CC BY 3.0)

1. Introduction

Located at the centre of Kowloon Peninsula, Mong Kok has long been a place with seemingly conflicting traces. First, it has been a crux of local culture – gathering local shops (hawkers, street food, niche stores for youngsters), local people and tourists in seek of the authentic side of Hong Kong. It is visited in the highest frequency by tourists and locals as a cultural and leisure centre respectively. It is known for its chaotic, bottom-up spirit. Second, and a phenomenon that gains momentum later, Mong Kok lies at the centre of the MTR network and serves as the transfer station for two major metro lines. It represents a homogenizing force, with its orderliness and its role as a driver of large-scale urban development. This project examines the juxtaposition of these two forces in general, and in particular whether the MTR’s dominating influence has affected local culture and whether there is any conflict between these contrasting traces.

2. A Cultural Geographical Perspective on Mong Kok

Our investigation is structured around the following question: Will the MTR, as one of Hong Kong’s key drivers of urbanization, eradicate the local culture embedded in Mong Kok?

To reveal the relationship between daily commute and spatial arrangements of Mong Kok, Lefebvre’s spatial triad is used as a theoretical perspective to analyze how the space in Mong Kok interact with the culture there, and contribute, if any, to the existing culture.

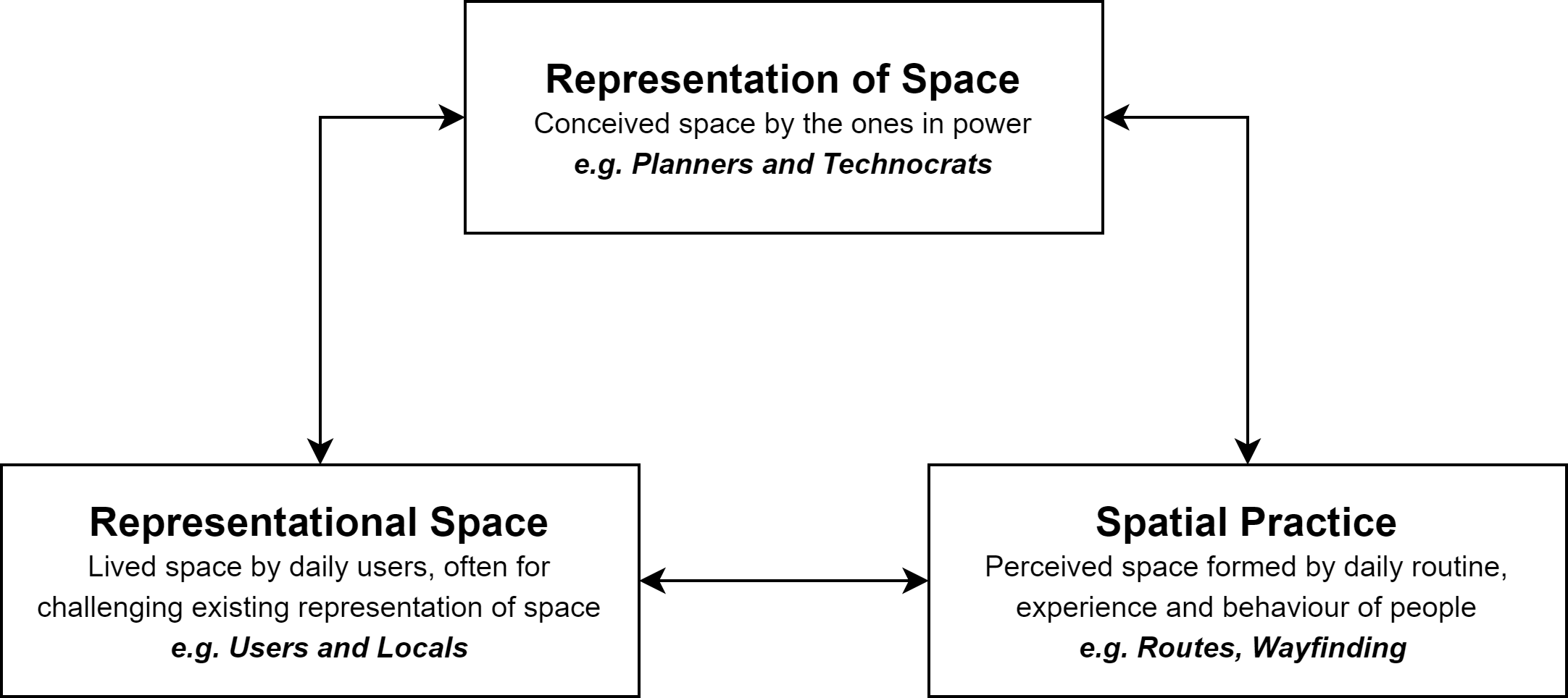

Lefebvre’s spatial triad consists of three elements:

- Representation of space is the conceived space by the ones in power in influencing the city plans and urban planning, e.g. scientists and planners;

- Representational space is the consumption of space by daily users, e.g. using the space according to personal feelings, intuition, and habits.

- Spatial practice is the daily usage of space on which we implement our knowledge

Figure 2. An illustration of Lefebvre’s spatial triad (Source: Lefebvre, 1991)

The spatial triad provides a way to analyze how space is both a tool and a result of the power struggle between social groups with different levels of power. It draws attention to (A) how users of stronger or weaker power conceive the places based on their daily routines and habits, and (B) how the conception of spaces by daily users reshape the conception of space by urban planners. Specifically, we argue that the complicated, fast-paced urban spatial arrangement in Mong Kok – i.e. the representation of space developed by the MTR – has limited the growth of the local culture.

3. Empirical Analysis

Representational space and representation of space in Mong Kok: Impacts of the MTR

Once a farming village, Mong Kok began to flourish at the beginning of the 20th century as a commercial area. It has since evolved into a melting pot of ‘street culture’, a set of ‘practices, styles, symbols, and values associated with, adopted by, and engaged in by individuals and organizations that spend a disproportionate amount of time on the streets of large urban centres’ (Ross, 2018, p. 8). It is known for its open-air markets, where locals and tourists alike visit the hawkers for knockoffs and street food. It is also known for its appeal to teenagers, who patronize the area for its concentration of entertainment venues, electronics stores and vendors of trendy products. It is furthermore known for its pedestrian zone, whose success in attracting a large number of street performers provoked local residents’ opposition that led to its abolition.

The chaos and crowdedness bolstered by these diverse traces of culture stand in sharp contrast to the orderliness brought by the MTR. As Hong Kong’s railway monopoly, the MTR structured the culture of Mong Kok and other parts of the city through its extensive railway network. With the power to enforce a set of by-laws on any railway premises, the MTR has transformed wherever its railway reaches into spaces with ordered cultures. As a notable example, the MTR stations are full of instructions – from exits, directories, the flow of people, where to stop and where not to etc., from eye level, above and below, with none that was left with no regulatory guide. These signs were accompanied by non-stop announcements, from reminders of last trains and safe use of elevators, to appeals for passengers to squeeze into the carriages to make room for others.

Owing to the dominance of cultural values embedded by the MTR development, these geographical borders further extended beyond the metro stations and infiltrated various streets and landmarks. Signs and guides for metro stations and exits are ubiquitous in the public spaces including various pedestrian walkways, flyovers and shopping centres.

Figure 3. The MTR stations in Mong Kong are highly regulated spaces.

Evidence of transformation: Spatial practice in wayfinding and navigation

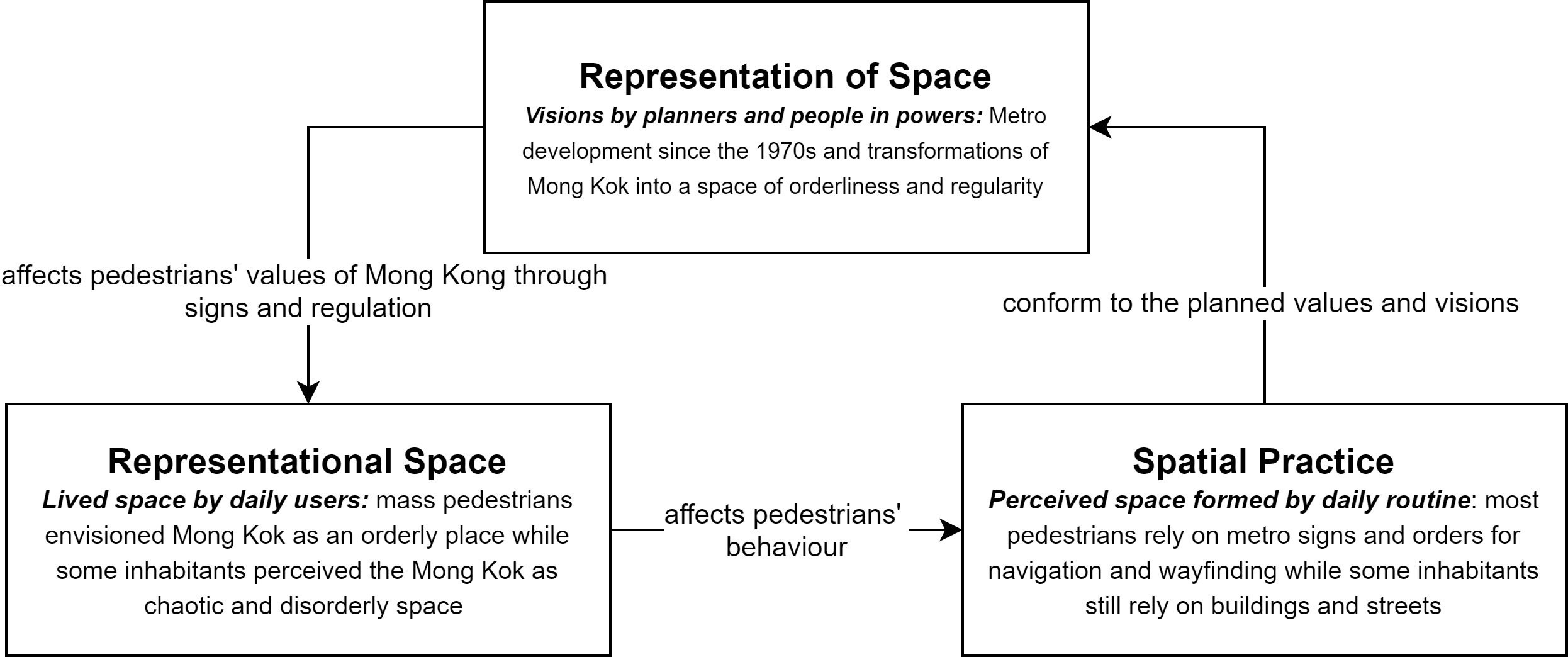

An emerging trace in unveiling the impact of metro developments on spatial practices is the pedestrians’ changing sense of direction and wayfinding behaviours. Before the construction of the MTR station, most residents relied on landmarks and streets for navigation which represents the chaotic and yet disordered traces. The Mong Kok streetscape has undergone significant transformation and socialization. Since the 1970s, commercial activities have burgeoned and grown around nodes of the MTR stations given their high accessibility. Old buildings such as tonglau (唐樓) are hence gradually overhauled by office complexes and malls such as Langham Place, which become the new exits of the metro stations. The transformation of space has then marked the transition of value from disordered yet continuous space into socialized space advocating formality, orderliness and regularity.

These transformations in cultural traces are evidenced by the results of our street survey. The MTR exits have become the dominant trace which people depend upon for navigation. During our field study, 60.9% of our respondents use metro signs and exits to find their ways and destinations in Mong Kok. Some would identify the location of a place by its closest MTR exits. Some even deliberately move from one location of Mong Kok to another through the MTR station in order to orient themselves with the aid of the station map. At the same time, 84.5% of the respondents indicated that they were unable to identify the streets of Mong Kok without the aid of an MTR map. These findings suggest that most of the places in Mong Kok have been socialized by the values of orderliness and regularity introduced by the dominating power of metro stations. These transformations have, thereby, significantly reshaped the pedestrians’ conception of space and directions, as well as their behaviour in their navigation of Mong Kok.

These spatial practices are in contradistinction to those of the local inhabitants and daily users. Long-term residents inhabited for many years tend to rely more heavily on the street names than their non-residential counterpart, who can barely identify other parts of Mong Kok besides the town centre due to the crowdedness and disorganized culture of the streetscape. While youngsters tend to rely on metro signs and iconic, middle-aged and senior citizens roam around based on their knowledge and impressions on the streetscape. Owing to more established and complete memory of the urban areas, many residents can visualize Mong Kok by street names and even demolished buildings when compared to their younger counterparts. However, as the dominating metro culture continues to develop, it is expected that fewer and fewer pedestrians may perceive the space by buildings and streets, and hence vanish of the disorderliness of street cultures.

Figure 4. An illustration of Lefebvre’s spatial triad and the conflicts between street and metro culture in Mong Kok

This finding suggests that the formation of new and organized cultural traces as facilitated by the MTR development has significantly altered people’s conception and knowledge of a space and how they navigate. These metro culture has been acting as a dominant force that reshaped and socialized the streetscape in Mong Kok. These findings generally correlate with Lefebvre’s idea of the spatial triad. While people in power may structure their representation of space through imagining Mong Kok into an organized city with full metro coverage and signs in various public spaces, other users may have their own values assigned to the landscape through representational space. Both of these traces are merged into the spatial practice through everyday routine and experience of wayfinding and navigation in Mong Kok.

4. Conclusion

This study attempts to integrate Lefebvre’s spatial triad into the examination of how railway developments significantly reshaped the distinct cultural practices in Mong Kok. While the spatial arrangements in Mong Kok are heavily regulated by organized yet dominant metro culture, pedestrians spatial practice and daily routine of navigations and wayfinding have also been socialized by the metro’s value of formality and regulation. However, the government and the MTR have not been all-powerful. The subcultural groups could respond with tactics through spatial reimagination and practices to counter the representation of space and values by the powers. For instance, re-imagining our own short-cuts and alternatives to the directions of the metro signs on skywalks may allow us to explore and experience Mong Kok in unconventional ways, thereby defying conventions embedded by metro cultures.

Reference

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Oxford: Blackwell.

Ross, J. I. (2018). Reframing urban street culture: Towards a dynamic and heuristic process model. City, Culture and Society, 15, 7-13. doi:10.1016/j.ccs.2018.05.003