This page is developed based on a project undertaken by students ... in 2018-19.

1. Introduction

Strolling on the streets in Keelung, one would be amazed by the cultural diversity which shapes the city’s distinctive local landscape. Located at Taiwan’s northern tip, Keelung has been one of the important gateways to Taiwan.

This research departs from the cultural geography perspective that a place is formed by cultural traces left by a series of conflicts and integration of cultures. In the case of Keelung, its cultural landscape is formed through the interplay of different prevailing socio-political forces during the reign of three governments:

- the Qing Court (1683–1895), under whose reign people from southern Fujian, also known as Minnan (閩南), migrated to Keelung;

- the Japanese colonial government (1895–1945), which took over Taiwan after Qing’s loss in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), and

- the Republic of China (ROC) government (since 1945), which acquired Taiwan’s sovereignty after Japan’s defeat in World War II.

Location of Keelung in Taiwan (Map by Luuva / CC BY-SA 3.0)

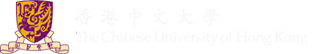

2. Cultural Geography Perspective in Use

From a cultural geography perspective, a place is formed by various cultural traces which reflect and reinforce a particular cultural order. Every place has its own cultural order, which is defined by the social groups possessing dominating power. The presence of cultural order means that some groups are accepted in a place, while others are marginalised, if not completely crowded out. Cultural traces in a place captures the outcome of the interaction between social groups, and their relative position in the cultural order. As such orders evolve over time, older cultural traces may be erased by, overlaid upon, or integrated with newer traces, creating a complex cultural landscape.

Keelung is a sum of Minnan, Japanese, and ROC culture, with the assimilation managed by the government and the acculturation promoted by citizens through conflicts and compromises. Governmental assimilations added new traces to erase the legacy of the last era and to propagate the dominant culture. In spite of the governmental unyielding changes, the public also encounter conflicts between different cultural beliefs when new culture entered Keelung. The clashes may result in a mixture of distinct beliefs after a period of time. Although new cultures were not accepted when they first entered Keelung, as time passes, people gradually integrate foreign cultures with their own culture, and that forms the modern Keelung.

Socio-political conflicts as well as traces of cultural integration can be observed throughout Keelung’s development since the 19th century. The following discussion will evaluate how a combination of Minnan, Japanese and ROC influences have given rise to three distinguishing features of Keelung: the city’s Ghost Festival, the spatial complex of Dianji Temple (奠濟宮) and Miaokou Night Market (廟口夜市), and the city centre’s road system.

3. Traces of Cultural Integration and Transformation

3.1 Keelung Ghost Festival

Keelung Ghost Festival is an intangible cultural trace of the armed conflicts between migrants from different parts of Minnan, a region separated from Taiwan by the Taiwan Strait. During the Qing Dynasty, many Minnan people migrated to Taiwan in seek of a better life, with Keelung being one of their popular destinations. These people came mainly from two parts of Minnan, Zhangzhou (漳州) and Quanzhou (泉州). Due to their different origins, religions and cultural practices, these new settlers ran into a series of deadly confrontations during the 1850s, now collectively known as Zhang-Quan Conflicts (漳泉械鬥) (Wei, 2011). The Zhangzhou people won and took over the land near Keelung Harbour (基隆港), while the Quanzhou people were forced to move inland to Nuannuan District (暖暖區).

District map of Keelung City, Taiwan (Adapted from: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b1/Keelung_districts_map.svg)

To avoid further bloodsheds, leaders of the Zhangzhou and Quanzhou migrants eventually reconciled in an interesting manner. Instead of physical confrontations, they agreed that their communities would compete in hosting rituals during the Chinese Ghost Festival, which falls on the 15th day of the seventh month of the Chinese calendar, to appease and sate the deceased (Wu, 2009). The competition, represented at first by 11 and later 15 clans, continues to date in two parts. First, the clans compete across years as they take turn to decorate the main alter (主普壇) of the year as elaborately as possible. Second, the clans also compete head to head in the same year in organising the most eye-catching street parade. Given its colourfulness, Keelung’s Ghost Festival attracts a lot of local visitors and foreign tourists, and earns the name of one of Taiwan’s top twelve festivals identified by the Taiwan Tourism Bureau.

The three-storey main altar of Keelung Ghost Festival, currently used as the Keelung Mid-summer Ghost Festival Museum

(Photo by Eugene Yeh / Photo courtesy Taiwan Tourism Bureau)

3.2 Dianji Temple and Miaokou Night Market

The history of Minnan migrants also leaves a tangible trace in Keelung – Dianji Temple, whose siting reflects the legacy of Zhang-Quan conflicts. Established in 1875, Dianji Temple was built by the Zhangzhou community to worship the Sage King Kaizhang (開漳聖王), a Minnan folklore hero, for his loyalty and effort in developing the Fujian province (Keelung Municipal Government, 2018). At the back of Dianji Temple lies Qingning Temple (清甯宮), built by the Quanzhou community to worship the Gods of the Water (水仙尊王). Since Quanzhou people lost in the conflicts with Zhangzhou people, they were only qualified to build their temple as a smaller building behind Dianji Temple.

Keelung Dianji Temple (Photo by lienyuan lee / CC BY 3.0)

In addition, Dianji Temple showcases the compromise and coexistence of Japanese and Chinese cultures. The temple’s main hall stands two pairs of pillars decorated with different motifs. Erected by the Japanese colonial government, the older pair is decorated with patterns of flowers and birds, as they are symbols of good fortunes and a free spirit in Japanese culture (Chen, 2005). On the contrary, added by the ROC government, the younger pair is decorated with patterns of a Chinese dragon, reinforcing traditional Chinese culture in the temple.

Pillar with pattern of a dragon in Dianji Temple. (Photo by yeowatzup / CC BY-2.0)

The significance of Dianji Temple has evolved over time with the development of Miaokou Night Market around it. In the past, countless people visited Dianji Temple for worships. This attracted many vendors to operate around the temple. The night market so formed is named ‘Miaokou’, which literally means the entrance to a temple. However, in modern days, people are less superstitious and visit Dianji Temple as tourists instead of disciples. Therefore, the temple’s social significance as a worship venue is gradually decreasing, while people pay more attention to the night market, particularly the wide range of food it offers, including those of Japanese, Minnan, Zhejiang, and Taiwanese origins. Miaokou Night Market has taken over the status of Dianji Temple as the most important spatial feature of the local area at which they are located.

Miaokou night market (Photo by Wu-Chih Hsueh / Photo courtesy Taiwan Tourism Bureau)

3.3 Keelung’s Road System

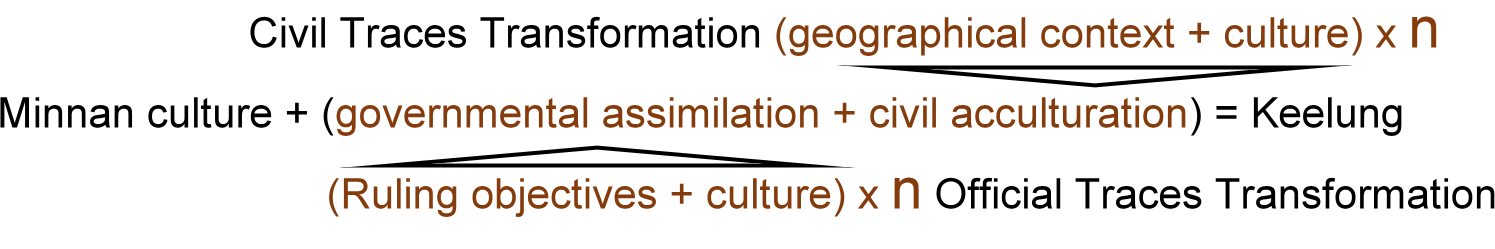

The road system of Keelung is a typical example of spatial transformation for economic and political goals. The system first took shape during the Japanese colonial era, when the colonial government considered Keelung a place with great development potential but physically in disorder. To develop Keelung into a modern port city, the colonial government formulated the Keelung Municipal Improvement Plan in 1905. The plan introduced a grid of modern roads and sewers to facilitate modern transport and reduce flooding risk (Ho, 2018).

Keelung’s grid road plan, 1945 (Map by U.S. Army Map Service / Courtesy University of Texas Libraries)

After World War II, the ROC government was eager to erase Japan’s colonial influence and assert its authority on the island. In Keelung, the ROC government preserved the grid of roads, but renamed them according to the ‘eight virtues’ generalised by Sun Yat-sen, the founder of ROC, from traditional Chinese values (Lee, 2016). They include dedication (忠, zhong), filial piety (孝, xiao), benevolence (仁, ren), love (愛, ai), trustworthiness (信, xin), justice (義, yi), peace (和, he) and equality (平, ping).

Keelung’s roads named after eight virtues: Ai 3rd Road (left) and Xin 2nd Road (right)

(Left and right photos by Solomon203 / CC BY-SA-4.0)

4. Concluding Thoughts

Owing to conflicts and compromises among the Minnan migrants and the ruling powers in the past hundred years, Keelung, a small city at the top of Taiwan’s map, bolsters a range of material and non-material traces which embody the cultural influences from the Minnan communities, the Japanese colonisers, and the officials of the ROC government. From these mesmerizing and intriguing traces, we can retrace and study how dominating powers and transgression of different parties shape the cultural diversity and distinctive cultural landscape of the city over time.

Roses always come with thorns. Foreign cultures, while giving birth to Keelung’s cultural diversity in the past, may dampen its cultural diversity nowadays. Under the influence of globalization, local cultures are at risk of being banished. In recent decades, the local government developed the cruise economy in Keelung port, driving up land rent in Keelung. Some local vendors cannot afford the rising cost and have been displaced by stores of multinational corporations with stronger financial strength. Without concerted effort to conserve the local ways of living, Keelung’s cultural diversity and continuity may cease to exist. Whether Keelung can preserve its uniqueness in cultural terms is a question that deserves our further attention.

References

Keelung City Government.

(2018). Keelung Travel - Dianji Temple. Retrieved from https://tour.klcg.gov.tw/en/attractions/temples/奠濟宮/

Wei, L. (2011). Chinese

festivals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wu, H. (2009). Kinship

Resolution to Replace Regional Conflicts? The Ghost Festival in Keelung and the

Surname Rotation System. The Journal of History, NCCU, (31), 51-95.

何昱泓(2018年09月21日)。〈鍵盤基隆小旅行:從築港工程到地下旭川,百年來港都大改造的歷史軌跡〉。取自https://gushi.tw/old-times-keelung/

李筱峰(2016年03月08日)。〈基隆地名的故事〉。取自http://www.peoplenews.tw/news/878a496e-49b2-4456-b38a-0ac52e66d532

陳凱雯(2005)。〈帝國玄關─日治時期基隆的都市化與地方社會〉(碩士論文)。取自http://ir.lib.ncu.edu.tw:88/thesis/view_etd.asp?URN=91125015