Religious Culture and the Place of Belief

Introduction

Nestled between towering mountains and calving glaciers, Tibet evokes a lot of fascinations about what its loftiness and remoteness breed. Such fanciful interest is often directed at the spiritual aspects of Tibet as the origin of Tibetan Buddhism (藏傳佛教). In the following, we examine how Tibet has developed as a place of belief, where Tibetan Buddhism has held pervasive sway in the lives of the Tibetan people. Specifically, we examine how the emphasis of centrality and cyclic existence in Tibetan Buddhism are physically inscribed in Lhasa (拉薩), Tibet’s capital city.

Tibetan Buddhist Monks (Photo by Ani)

Nature, Bon and Tibetan Buddhism

Tibet is bounded on the north and east by the Central China Plain, on the west by the Kashmir Region of India and on the south by Nepal, India, and Bhutan. It is located on the Tibetan Plateau (青藏高原), where some the world’s highest mountain peaks, including the Himalayas (喜馬拉雅山), are found. With an average altitude of over 4,000 m, this highland area is often known as the ‘roof of the world’. The region is the source of many of the world’s most important rivers, including the Indian River (印度河), the Ganges (恆河) and the Mekong (湄公河).

Living in an ecologically diverse and challenging environment, indigenous Tibetan felt that their life was at the mercy of mother nature. They practiced a natural-based religion called Bon (苯教). They worshipped a wide range of natural phenomena and features – from sun, moon and thunders in the sky to mountains, rivers and animals on the ground – which they believed are inhabited or regulated by spirits.

Namtso, the heavenly lake of the Tibetans (Photo by Ani)

However, the dominating influence of Bon to Tibetans began to be challenged in 7th century, when King Songtsen Gampo (松贊干布) actively promoted Buddhism. Songtsen Gampo was known as a powerful leader who united the then various Tibetan principalities into a single kingdom. During his reign, many of Tibet’s highly civilised neighbours, such as Nepal, India and the Tang Empire, were Buddhist states. Observing the close links between Buddhism and the culture of his neighbouring powers, Songtsen Gampo decided to introduce Buddhism to Tibet to civilise his people and strengthen its kingdom (Sangharakshita, 1999). He started building Buddhist temples and promoting Buddhist teachings across Tibet.

The development of Buddhism in Tibet subsequently faced a long period of resistance from the Bon followers. They included the noble families whose power were undermined by the Buddhist kingship, and the Bon priests whose livelihood were threatened (Sangharakshita, 1999). It was not until the 11th century that, after successive rounds of social and political struggle, did Buddhism finally acquired dominance over Bon in Tibet. This however did not result in the complete erasure of Bon from the Tibetan cultural landscape. While inherited from India, the Tibetan practice of Buddhism has assimilated some of the domestic ideas and practices of Bon. This process of ‘indigenisation’ (本土化) has shaped Tibetan Buddhism into a distinctive branch of Buddhism. For example, Tibetan Buddhism retains the Bon worship of natural entities. Besides temples and buddhas, Tibetan Buddhists also pray to mountains and lakes accorded with sacred status, as well as mounds of mani stones (瑪尼堆) – stones inscribed with the six-syllable Buddhist mantra (六字真言) (Huang and Liu, 2010).

A mani stone mound along Nyang River, southwest Tibet (Photo by Wikipedia user 山海风 / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Centrality: From Worldview to Urban Layout

The worldview of the Tibetans is underpinned by the idea of centrality. According to Tibetan Buddhism, the universe is centred upon a mountain named Mount Meru (須彌山) (Samuel, 2012). The heaven of gods and demigods is located above the mountain, while the hell lies below it. Around the Mount Meru are continents and subcontinents where human beings live. Although this view of centrality was inherited from Indian Buddhist texts, it was not difficult for the Tibetans to find resonance with it – living on an almost boundless terrain, ancient Tibetans developed their sense of belonging and orientation around visually prominent features on their horizon (Huang & Liu, 2010).

Mount Meru, depicted on a piece of silk embroidery produced in the 18th century

(Photo from the Walters Art Museum / Public Domain)

The emphasis of centrality in Tibetan Buddhism has influenced the spatial organisation of settlements in Tibet. The development of Lhasa, Tibet’s religious, economic and administrative centre for centuries, assumes a radial pattern around a central point, namely, the Jokhang Temple (大昭寺). Built in the 7th century, the Jokhang Temple houses the Jowo Rinpoche, a statue of the Buddha at the age of 12. Since the statue was believed be blessed by the Buddha himself, Tibetans, as followers of Tibetan Buddhism, have enshrined the Jokhang Temple as their most sacred temple. Conforming to the principle of centrality, Lhasa’s main roads all radiate from the Jokhang Temple. Moreover, no buildings around the Jokhang Temple are allowed to be built taller than it so that it can be seen from anywhere in Lhasa.

Jokhang Temple (Photo by Wong Ting Kwan)

Circling of and in Life

Another central belief of Tibetan Buddhism is cyclic existence (輪迴), the idea that one would be reborn after his/her death. According to Tibetan Buddhism, life circulates between six worlds: (i) the heaven of the gods, (ii) the realms of the demigods who are at constant war with the gods, (iii) the world of human beings, (iv) the realm of animals, (v) the realm of the spirits fated to perpetual thirst and hunger, and (vi) the hell-realms with dreadful punishments of the cold and hot hells (Samuel, 2012, p. 91). The world to which one would be reborn is a function of the merit one accumulated during one’s lifetime. Following the teaching of Buddha, Tibetan Buddhism suggests, is the only way to prevent one’s successive rebirths in the undesirable worlds.

Tibetan Buddhists have figuratively incorporated the cyclic nature of their existence into their everyday rituals. As a symbol of their religious practice, Tibetan Buddhists regularly spin a prayer wheel (轉經筒), a handheld cylindrical wheel containing paper printed with mantras. They believe that spinning a prayer wheel allows people to accumulate the same merit as orally reciting the sutra. In many Tibetan temples, stationary prayer wheels are installed in a row, allowing people to turn the wheels one by one by sliding their hand over them.

Prayer wheel: A symbolic marker of Tibeten culture (Photo by Ani)

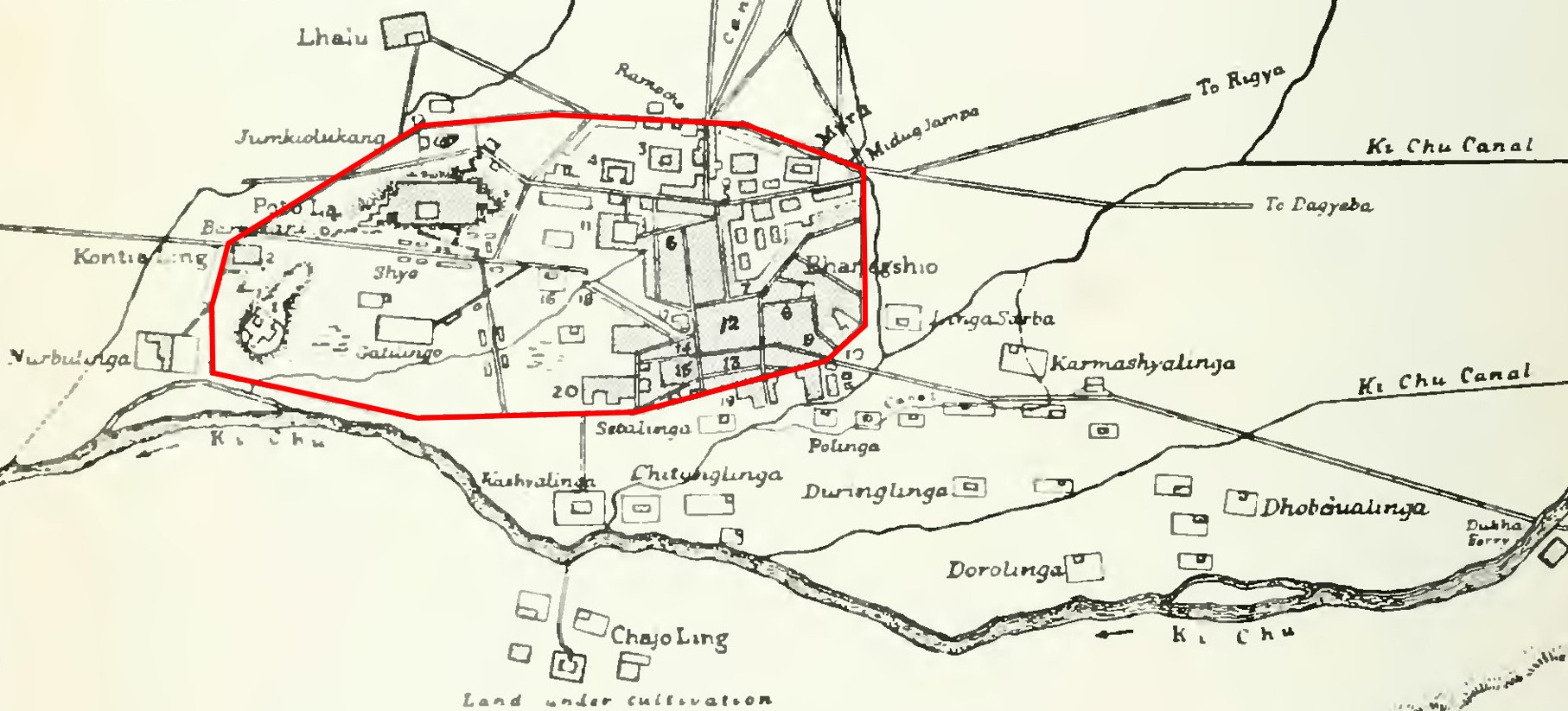

In Lhasa, Tibetan Buddhists also take ritual walks in a clockwise manner along the city’s three pilgrimage circuits. These circuits share the Jokhang Temple as their common centre – yet another illustration of the principle of centrality. The innermost circuit, the Nangkhor (朗廓), runs around the main hall of Jokhang Temple, where the Jowo Rinpoche is housed. The middle circuit, the Barkhor (八廊), circumscribes the Jokhang Temple. It was formed as a street along which pilgrims to the Temple and businessmen gathered. The outermost circuit, the Lingkhor (林廓), encircles the urban core of Lhasa. It takes people two to three hours to complete a full circle of walk.

Extract of a map of Lhasa drawn by Indian surveyor Kishen Singh in 1878. The circuit of Lingkhor in marked in red.

(Original image in Public Domain)

References

Huang, L. & Liu, C. (2010). The image-meaning relationship between Tibetan traditional architecture and religious culture [西藏傳統建築空間與宗教文化的意象關係]. Huazhong Architecture [華中建築], 2010(5), 134–137.

Sangharakshita (1999). Tibetan Buddhism: An introduction (reprinted with corrections). Birmingham, UK: Windhorse Publications.

Samuel, G. (2012). Introducing Tibetan Buddhism. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.