Havens of Traditional Widsom

Introduction

As bulldozers proceed apace to modernise and urbanise China, concerns are growing about the fate of the country's ancient villages. Most of the ancient villages that survive today were built during the Ming or Qing Dynasty, with a minority of them dating back to the Song Dynasty. These ancient villages demand our attention and protection because they are havens of traditional Chinese wisdom. They are tangible traces of how Chinese historically conceived of their society and their interaction with the surrounding environment.

Fengshui and Ancient Villages

Rooted in the idea of an integrated and holistic universe, fengshui is a set of traditional Chinese theory on how people can achieve a harmonious relationship with nature through careful planning and design of their built environment. Its emphasis on nature is obvious from its two constituent Chinese characters: while 'feng' means wind, 'shui' means water.

According to fengshui, nature is filled with qi (氣), an intangible form of energy which vitalises everything. Its flow is 'responsible for the retention or dissipation of anything', including 'health, wealth, fortune and intelligence of human beings' (Mak and So, 2015, p. 208). People can therefore lead a better life if they live at sites where qi is accumulated. As a result, the practice of fengshui is about locating and designing settlements with a view to maximise the level of qi for their inhabitants.

Fengshui forest at the back of a village in Lam Tsuen, Hong Kong (Photo by Chong Fat / CC BY-SA 3.0)

This thinking of qi gives rise to two principles which were followed in the planning and design of many ancient villages. The first principle is avoiding wind. Fengshui suggests that wind can blow qi away (Mak and So, 2015, p. 51). Since China experiences cold currents from the north in winter, it is better to locate villages in south-facing sites surrounded by mountains in the north. In so doing, villages can be shielded from the northerlies and can therefore retain qi better. On plains without mountains, fengshui recommends people to instead plant trees to the north of their villages as windbreaks to help retain qi. Forests grown for this reason are known as fengshui forests (風水林).

The second principle is finding water. According to fengshui, qi is kept and accumulated in water (Mak and So, 2015, p. 51). Resembling blood flowing in our body to keep us alive, water flowing in nature carry qi to villages for their people to thrive. As a result, ancient villages were typically built near a peaceful lake or a curving river enclosing them – fengshui identifies both features as conductive to the accumulation of qi. On the contrary, villages would avoid locating next to a straight river, which is seen in fengshui as flushing qi away.

Central pond in Hongcun, a village in Anhui first built in the Ming Dynasty (Photo by Mulligan Stu / CC BY 2.0)

Defence and Ancient Villages

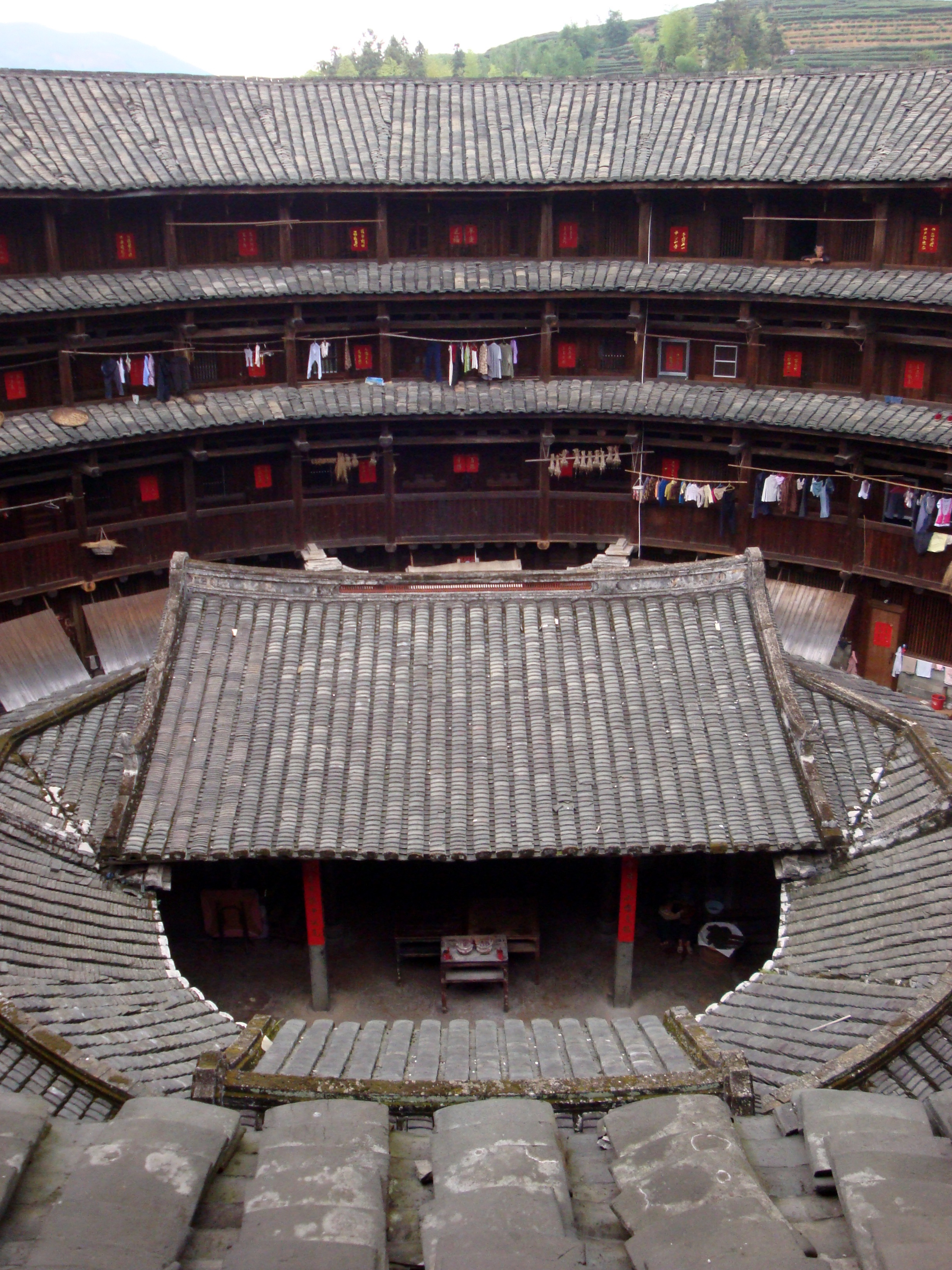

Apart from making peace with nature, ancient Chinese were also concerned about protecting themselves against threats from the outsiders of their communities, from local bandits to foreign invaders. Defence constitutes another important consideration in the planning and design of ancient villages. A famous example is tulou (土樓), or 'earthen dwellings', built by the people of Hakka (客家) in Fujian province.

The Hakka are Han Chinese whose ancestors migrated from the Yellow River Basin to south China to flee successive political and military conflicts in north China. This history is reflected by the very name of the Hakka, which literally means 'guest families'. As migrants, the Hakka were often in conflict with their indigenous neighbours over resources and territories. As a result, defence is a centrepiece of Hakka culture and is emphasised in the construction of Hakka settlements.

A tulou as seen from above (Photo by Gisling / CC BY 3.0)

A tulou consists of a collection of buildings surrounded by a massive wall of up to five stories. Its wall is built with rammed earth – from which tulou earns its name – and reinforced with multiple layers of iron plate, bricks, bamboo or other locally available materials. To prevent invasion, each tulou has only one entrance, and its lower stories do not have any window. At higher stories, some holes were drilled through the wall to shoot down attackers.

Defence is not just about building walls against external threats – it is also about promoting cohesion and mutual support among people living behind the walls. The centripetal internal layout of tulou is conductive to a communal spirit essential for security. Building within a tulou are often organised in concentric circles, with their doorways facing the centre. During an attack, this concentric organisation facilitate the recruitment of residents from across the tulou for defence. It also allows people to have easy access to food and water from the food storages and wells at the centre of the tulou. Also found at the centre of a tulou is a hall for social gathering and ancestral worship, which practically and symbolically promotes unity among everyone living around it.

Centripetal layout within a tulou (Photo by fisher0528 / CC BY 3.0)

Reference

Mak, M. Y., & So, A. T. (2015). Scientific feng shui for the built environment: Theories and applications. Hong Kong, China: City University of the Hong Kong Press.

The Politics of Valued Environments

Nature and Culture: An Interrelated Pair

Notably in the Western World, nature is often thought to be independent from human communities and, by extension, culture. However, as this page will show, nature – or the natural environment – is in fact a key part of the context of cultural processes. An ensemble of biotic and abiotic features, it both shapes and is shaped by mankind and their culture.

On one hand, nature presents as biophysical constraints to human activities. Cultures developed in different communities often bear the imprint of their respective adaptations to prevailing natural conditions. Consider, for example, the suspended wooden houses built by Miao people living in mountainous parts of Guizhou. In this way, physical diversity and cultural diversity can be highly correlated.

On the other hand, people modify nature as a key site of expression of their culture. Their modifications can be symbolic, related to assigning particular meanings to natural features, such as identifying a lake as sacred. They can also be more material and visible, as physical transformation of natural landscapes for various socioeconomic purposes, from resource extraction and opening up of new farmland. Given these considerations, natural features can be cultural traces as well, bearing symbolic and material impacts of culture.

Nature, Culture and Politics

Behind these modifications, or cultural traces, that people leave on nature is indeed a complex web of power relations. As the fundamental argument of an emerging research called political ecology (Robbins, 2012), nature is inherently political. This is because conflicts and struggles arise from time to time between individuals or communities over how we should engage with nature. This question of ‘how’ is meditated by one’s cultural background, which gives rise to particular views on nature’s values.

One of the cultural roots of political tension around nature nowadays is the culture of commodification. This strand of culture treats everything as a commodity, which can be assigned with a price and sold for a profit. Following this line of thought, nature should be managed in a way which maximizes the economic benefits it yields. Modification of nature is possible, even necessary, if it can help unlock more profit-making opportunities from nature. An example of nature’s commodification is the development of nature tourism, under which nature is sold to tourists as tourism products.

Commodifying nature through tourism development

Fee-charging elevators are built in Malinghe Canyon, Guizhou Province, so that tourists can reach the bottom of the canyon more easily.

(Photo by Calvin Chung)

As commodification of nature proceeds, political conflicts may arise in two ways. First, people who value nature differently may challenge the idea of commodifying nature. Conservationists may reject attempts to develop nature tourism because of its potential damages to natural landscapes and wildlife. Second, for those endorsing the culture of commodification, they may compete with each other over who can commodify nature and reap benefits from it.

In China, economic reform since 1978 has emphasised a greater role of price signals in resource allocation, and the imperative of economic growth. These changes give momentum to the idea of commodification of nature. Local governments have turned many of the country’s natural wonders into tourist attractions to promote local economic development.

In the following, we consider what has happened to China’s Danxia landform (丹霞地貌), a feature recognised by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as World Heritage since 2010, to unpack the political and physical implications of an emerging culture of commodification on nature.

Inscribing Danxia Landform as a UNESCO World Heritage

What is Danxia landform? What is UNESCO World Heritage?

Danxia landform refers to an erosional landform unique to China. It consists of red sedimentary beds characterised by steep cliffs. The landform was named after the mountain of Danxiashan (丹霞山) in Guangdong province, where Chinese scholars first identified it as a distinct landform category in the first half of the 20th century. The rugged landscapes produced by Danxia landform are rich in biodiversity, hosting about 400 rare or threatened species of plants and animals (UNESCO, n.d. a). In both geological and biological terms, Danxia landform is highly valuable to China and the rest the world.

Danxiashan, Guangdong Province

The literal meaning of ‘danxia’ in Chinese is ‘red sky glow’, which captures well the typical reddish appearance of the landform.

(Photo by Professor Peng Hua)

To promote effort to conserve Danxia landform, the late Professor Peng Hua from Sun Yat-sen University had led a dedicated team of experts to campaign for UNESCO’s recognition of Danxiashan as a World Heritage. Since 1972, UNESCO has maintained a World Heritage List (WHL). Sites are inscribed on this list if they have ‘outstanding cultural or natural importance to the common heritage of humanity’ (UNESCO, n.d. b). UNESCO intends to use the WHL to encourage effort in the identification, protection and preservation of cultural and natural heritage around the world.

Competition for the honour: motives and means

For a site to be considered for inscription on the WHL, it must first be nominated by its home country. However, a country can only submit two nominations to UNESCO each year. Given the difficulties involved in securing it, the World Heritage title means something rather different to the heralds of commodification. These people see it as a rare badge of honour which helps boost a site’s reputation. If a site is designated as World Heritage, it can be ‘sold’ to tourists or real estate developers at a higher price. In fact, commodification has become a key motivation for different sites and their local governments to secure national level nominations (Meskell, 2015).

The case for Danxia landform is even more complicated. Danxia landform is not found in Danxiashan only, but can be seen in various parts of China. As a result, Danxia landform’s bid as a World Heritage was made not in the form of a single-site nomination (which is more common), but a serial one. This means that multiple sites with Danxia landform was presented collectively in one nomination. In the end, six sites in south-eastern China has made onto the WHL as a series which showcases different stages of development of Danxia landform.

Location of the six sites of Danxia landform inscribed as World Heritage

All these sites are located in poor areas away from existing economic centres. There are hopes that the World Heritage honour can help these areas gain more attention for economic development.

Tension and competitions between local governments therefore took form of getting their Danxia landform shortlisted in the serial nomination. On one hand, they used different ways to prove the value of their respective Danxia landform features. For instance, in Guizhou, the government of Chishui City invited a total of 12 experts of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) from across the world for advice and suggestions on how to better the maintenance and development of the landforms. Some cities revised the whole management system of the landform, and some suggested possible criteria for shortlisting. To promote the Danxia landform as a tourist attraction, Hunan government spent a huge sum of money on holding a concert with famous singers. Some invited the mass media for promotion, for example, in the form of a travel mini-series in a popular TV show. People in Shaoguan were organized for a petition campaign around the city, ranging from schools, parks to businesses. City leadership, departmental leadership, tour guides and over a thousand members of the Communist Youth League participated in favour of nominating Danxia for World Heritage.

On the other hand, material changes took place in the Danxia landform sites, as local governments sought to improve their physical conditions in line with the requirements of being a World Heritage. Changes include building facilities such as museum, visitor centre, pedestrian pathways. In Chishui, the government ensured all their wires moved to be built underground, reset all the road signs, rearranged the housing of their people, removed the power stations around the landforms and more. However, in addition to building new facilities, changes also include demolishing original constructions. In Hunan section, a cross-border highways inside the heritage site was removed while in Guangdong, eight hotels were either shut down or relocated. Rather ironically, the drive for further commodification – in this case securing the World Heritage title, hinges on reversing some of the previous acts of commodification, whose traces are incompatible with the World Heritage’s goals of conservation.

The designation of World Heritage does not mean an end to tension around Danxia landform between nature conservation and commodification. The WHL has a withdraw mechanism – sites can be delisted if their conditions deteriorate. Yet, it is often no easy task to keep up with the good work done during the process of applying for the World Heritage status. There are fears that physically damaging development may revive in Danxia landform sites when local governments try to recover their huge spending on the World Heritage bid (Kor, 2016). Whether the World Heritage title is a blessing or a curse to Danxia landform therefore remains to be seen.

Summary

The Danxia landform’s bid for World Heritage status shows how nature and culture are linked in sometimes highly politicised ways. On one hand, Danxia landform forms the physical context of economic development in areas where it is found. On the other hand, local governments’ endorsement of a culture of commodification leave various traces on Danxia landform. Some of these traces are symbolic, most notably the fiercely competed title of World Heritage. Others are material, such as tourism development in Danxia landform sites partly suppressed during inter-locality competition for World Heritage nomination as an aid to tourism growth. The Danxia landform we see today is thus a power-laden co-product of nature and culture.

Reference

Kor, K. B. (2016,

July 26). Unesco heritage status a matter of pride and concern in China. The Straits Times, Retrieved from https://www.straitstimes.com/

Meskell, L.

(2015). Transacting UNESCO World Heritage: Gifts and exchanges on a global

stage. Social Anthropology, 23(1), 3–21.

Robbins, P.

(2012). Political ecology: A critical introduction (2nd ed.). Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

UNESCO (n.d. a).

China Danxia. Retrieved from https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1335

UNESCO (n.d. b).

Underwater cultural heritage inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/underwater-cultural-heritage/museums-and-tourism/underwater-cultural-heritage-inscribed-on-unescos-world-heritage-list/

And the Culture of Production

Creating traces all over the globe, capitalism is one of the most influential ideologies in contemporary societies. In China, since reform and opening-up (改革開放) started in 1978, capitalism has deeply penetrated into the Chinese society. With a diminishing role of central planning and a larger role of free market, some distinguishing values of capitalism, such as profit-seeking, privatization and commercialization are manifest in China since then. Through the constant interactions between men and social institutions, traces of capitalism have been continually created, substituted and renovated. Before discussing how capitalism transforms Chinese society, let us have a brief review of the core value of capitalism.

The Core Value of Capitalism

The essence of capitalism lies in profit-making. Capitalist culture is based on trading, be it services or products. Measuring the trading value with currency, a profit is made whenever the selling price exceeds the production cost.

Consider the example of Adam. Adam is a worker for a footware company. Every month he produces 100 pairs of trainers selling for $100 at the market. In other words, he can produce a market value equal to $10,000 monthly. If his wage is exactly $10,000, the footware company not only makes no profit but also suffers from a deficit due to the costs it incurs for factory operation and logistics. Therefore, if the footware company wants to make a profit, it must pay Adam less than $10,000, says $4,000. In this case, the difference between Adam’s wage and the value he produces is $6,000 (i.e. $10,000 minus $4,000).

How much can workers earn for the shoes they produce? (Photo by Coup d'Oreille / CC BY-SA 2.0)

Adam’s story illustrates the secret behind profit-making. According to Karl Marx, a famous critical political economic theorists, profit-making lies in the division of labor in production relationship: the bourgeoisie (or capitalists, 資產階級) who own the production capitals (or the means of production), and the proletariats (無產階級) who sell their labour in exchange for living. While workers create value with their labour on production, capitalists make a profit by maximizing what Marx referred to as 'surplus value', i.e. the value created by workers in excess of their own labour cost. In Adam's case, $6,000 is the surplus value appropriated by the footware company when shoes produced by Adam are sold.

Bourgeoisie specializes in pondering how to maximize as much surplus value as possible. There are many ways to do that, such as further suppressing the wages of labour. Remember surplus value is market values of production minus wages of labour. Therefore, many firms tend to relocate their factories to countries where labour cost is lower, such as China. The relocation of production line results in interactions of capitalist culture and various local culture, creating numerous and distinct traces.

Traces of Capitalism in Traditional Capitalist Countries: Fordism

Speaking of traces of capitalism, many would think of the legacy of Ford Motor Company (FMC), the world’s fifth-largest automaker. Founded in 1903 by Henry Ford in the American city of Detroit, FMC exerted profound influence over people’s lives not only by shaping the class of buyers, but also the way of living of its workers.

Ford was keen on raising productivity in the production process, for given the same wage level, higher productivity of workers yield a higher profit margin. Central to his productivity boosting plan was the introduction of the idea of producing cars on an assembly line. This involves lining workers up along a conveyor belt, with each worker focusing on one step of car production and passing his completed component to the next worker through the belt. Since each worker specialises on one step of production only, he may perform it more efficiently over time after repeated practice. And since each worker stays at a particular poisition along the conveyor belt for his work, it helps reduce his time wasted on moving around for his tasks. Meanwhile, Ford offered his workers a higher wage than many other manufacturers. Not only did he want to attract more productive labour to work for him, but he wanted to enable his workers to buy the cars they produced. In so doing, Ford promoted the development of a society founded upon mass production and mass consumption of standardised goods, a way of living now known as Fordism (福特主義).

The assembly line in FMC's factory stands as the trace of a profit-oriented culture of production

(Photo from Literary Digest, 1928 / Public Domain)

Opinions have differed on the impacts of Fordism. On the one hand, Fordism is praised as a way of living which supported the economic boom in Western nations after the Second World War. On the other hand, Fordism is criticised for how workers were exploited and alienated along the assembly line. For example, The New York Times once analogised Henry Ford with Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and called him 'Detroit’s Mussolini' because workers’ wives complained that the assembly line was more powerful than masters’ control over slaves with a whip to exhaust their husbands.

Traces of Capitalism in China: Foxconn

Since the

opening-up and marketisation of the Chinese economy in 1978, a flock of foreign

investors in China to take advantage of its preferential policies and cheap and

abundant labour resource for their manufacturing business, turning China into

the world’s factory. Arrived with these investors are not only their capital

and technology, but also the capitalist culture of production. It is in the

mushrooming number of factories that Chinese people, as workers, come into

contact with such culture. Unfortunately, the tough lives imposed by capitalist

production systems has sometimes proven too unbearable to the workers, leading

to miserable and deadly consequences.

A widely reported site of such interaction is the manufacturing facilities of Foxconn Technology Group (富士康科技集團), the largest Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEM) worldwide. It is an important component maker and final assembler for electronic products we use today. As its business rapidly expands, Foxconn needs not only a larger pool of workers, but it also needs each worker to work harder to meet its skyrocketing production needs. To make this possible, Foxconn has taken the Fordist model of mass production to the extreme. It operates like a ‘semi-militarized labor system’ (Pun et al. 2016: 172), in which assembly line workers are intensely supervised to maximise their output.

Electronics assembling in a Foxconn factory (Photo by Steve Jurvetson / CC BY 2.0)

The everyday life of Foxconn’s workers is very much organised around their daily production targets – their day of work does not end until they produce enough as required by their supervisors. This arrangement has resulted in long working hours without adequate pay. According to a 2010 study, to raise their company’s profit, Foxconn’s management would deliberately set up daily production targets which most workers could not meet during their regular shift, so as to force workers into free overtime work (Cai, 2012, p. 19). For workers who failed to meet the targets, they were penalized by their shop-floor foreman and managers, who were equally under pressure to meet their production targets, in forms such as scolding and not allowing to have meals. Those who managed to meet the targets did not have an easier life; rather, to profit further from their productivity, the management would assign a higher target on them.

Apart from a harsh time at work, Foxconn's workers also suffers from social atomisation, the process in which a person is detached from his/her social networks and become socially isolated. Foxconn’s business depends on the production needs of multi-national brands, such as Apple, HP and Dell. Changes in the nature and volume of demand made by these companies can have a major impact on Foxconn's production setups, such as large-scale reallocation of workers across assembly lines. This kind of reallocation is not confined to a single production plant, but across factories distributed in different cities or even provinces (Lin et al., 2016). Frequent shifts in workplaces sever workers from the social bonding they build up with their colleagues. Moreover, since many Foxconn’s employees are migrant workers, they are too poor to find a place to live. They live in Foxconn-maintained dormitories, where workers from the same origin or working in the same production department are not allocated to the same room. Given a lack of shared hometown culture or work experience, workers find it difficult to socialise with others in the dormitories and lack access to peer support when they are emotionally unstable. Under unbearable stress, some Foxconn workers committed suicide as a last resort to end their pain and express their discontent to the repressive capitalist regime in which they work.

Conclusion

To conclude, culture is not necessarily harmonious. Again, one of the essential values of capitalism is profit-seeking. This value emphasizes the exploits of surplus value and shapes the relationship between capitalists and workers. In other words, capitalist culture can be a product of the tension between the management and control over workers. In this sense, capitalism is not just a culture but a tool that nurtures certain power relationships, which may form conflicts and corresponding cultural traces. As capital flows internationally, the culture-shaping power of capitalism has been penetrating in more and more modern societies in ways unimagined.

References

Cai, S. (2012). Industrial organization in China: A case study of Foxconn's factory relocations (Unpublished master's dissertation). UCLA, Los Angeles, CA.

Lin, T., Lin, Y., & Tseng, W. (2016). Manufacturing suicide: The politics of a world factory. Chinese Sociological Review, 48(1), 1-32.

Pun, N., Shen, Y., Guo, Y., Lu, H., Chan, J., & Selden, M. (2016). Apple, Foxconn, and Chinese workers' struggles from a global labor perspective. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 17(2), 166-185.

Geographies of the Bordered Group

Introduction

Graffiti has always been framed as vandalizing and by-law contravention of public space worldwide. Despite its nature of unauthorized writing and drawing, it represents more than just chaotic messes but cultural traces of youth culture, borders, and politics of space. Before discussing the cultural geographies of graffiti, let us understand the reasons behind their daredevil pursuits and hence, how borders and politics of space regulate these cultures.

A Graffiti found in Bristol, United Kingdom (Photo by Mec Rawlings/ CC BY-SA 3.0)

Graffiti and Border: A Space for Youth and Artists?

Historically, people have been frequently

categorized into various social classes based on their different parameters,

such as age group, races, or socio-economic status. For instance, age

categorization is often used to label adults who are capable of driving or

purchasing alcoholic beverages. While these conventional bordering mechanisms are

often utilized for immediate labelling of people for various purposes, these

classifications may create “grey areas” for people not aligning with the

ordered mainstream culture (Anderson, 2010).

Youngsters, particularly, occupy ambiguous

positions in the social spectrum being bordered outside the public space

naturalized as either adult or child (ibid). These areas and public space, such

as playgrounds and pubs for adults and children respectively, cater only

passive recreation without space for the energetic youth. While age

classifications are useful for differentiating individuals requiring

supervision or could be morally or legally responsible for their behaviours,

classes outside of the conventional borders, such as the youth, elderly or

middle-aged, may not be able to find their positions in society (ibid). Turner

(1982), hence, described these youngsters as “liminal beings” due to their

undermined and marginal positions between the conventional distinctions of

“adult” and “child”.

Imagine if you were a high-school student and

you want to find somewhere to hang out with your friends or even to voice out

your opinions about the current socio-political debates, where would you go?

You are clearly over-aged for the playground while under-aged for most bars and

pubs. Although you seem more thoughtful than your childhood self, your opinions

are still undermined in the traditional social hierarchy as you are not

“mature” enough to be an adult and make the “right” judgements or observations.

What could you do to (re)claim your space? That is right: create your own.

There is where the notion of street and graffiti comes into place. As described by Anderson (2010), “street” refers not only to the sidewalks or streetscape but all public outdoor places that enable the celebration of individualism and expression of emotions of youngsters. These spaces are not regulated in an authoritarian way with strict rules and constant monitoring. They are not bounded by the adultized mainstream cultures and open for transgressive uses making them as “temporary autonomous zone” for youth.

A Graffiti found in Hong Kong Island (Photo by Richin Chin)

Whilst graffiti is a means for the youth to carve out space for them and establish their stake in the society in a world congested with borders which do not fit them , artists, on the other hand, may also be marginalized by these mainstream cultures. Very often, artists are avant-garde. Their works are experimental, radical, or unorthodox. Thus, they may be excluded by prominent and mainstream ideologies and cultures.

Graffiti, Space and Politics

Graffiti itself does not necessarily be related to political arguments, yet its spatial and temporal extensions are politically charged and infused. As Nandrea (1999) articulated, one of the key functions of graffiti is “to stake out gang territory, to lay claim to an alley, a corner, or an entire area symbolically fenced off by gang signatures”. Therefore, graffiti embodied the construction of new borders and ownership of space explicitly for teens and other undermined social classes as a challenge to the adultized or other mainstream cultures and laws questioning “whose place is this”? (Anderson, 2010). These proclamations may then trigger immediate responses from the state for reinforcement of their power in space through laws and regulations. This case symbolizes the idea of politics of space – the dynamic and struggle of power between the state and the public.

One example of the idea and the dynamic power

relations is the current trend of commodification and institutionalization of

graffiti and street culture. Commodification refers to the making of money out

of graffiti as a commodity while institutionalization refers to the formal

rules that regulate how graffiti is created. Graffiti, as argued by Nandrea

(1999), has been reconfigured and assimilated into the mainstream culture under

the capitalist realm through dismantling traces of youth and other subcultures.

The “street”, is thereby, transformed into “High Street”, as space where

business prospers and mainstream capitalist values exhibited while removing the

threat, transgression and non-commodifying nature possessed by the street

culture (Anderson, 2010; Cresswell, 1996). The contemporary trend has also

provoked debates on whether the commodified graffiti violate its nature for

expression of opinions and emotions of youth and other bordered groups.

The concepts of power struggle and cultural

commodification in street culture can best be illustrated by the 798 Art Zone

Case in Beijing and the Hong Kong Graffiti Development.

Commodification in Progress: the 798 Art District

What is the 798 Art Zone?

Located in Beijing, the 798 Art District symbolized the state’s attempt into the rhetoric glorifying of the creative industries while commodifying the street culture and graffiti. The 798 originated as a state-owned factory complex for electronics and weapons production and had been almost empty after most industries were relocated since the 1980s. The artists have then transformed the old industrial areas and reinvigorated the area into a cultural and artistic enclave with innovative and young vibes from young artists of various backgrounds (Currier, 2008). While encouraging cross-cultural collaborations and explicit expressions of creativity through graffiti, architecture and artefacts, it has since then debuted and shined at the international stage as a celebration of creativity (Brunner, 2017).

Graffiti found in 798 Art Zone (Photo by Calvin Chung)

Struggle and competition of street and mainstream culture

The 798 Art Zone illustrates the relic of the power struggle between the marginalized classes of youth and artists with the mainstream culture for public consumption during its course of development and two phases of transformations (Zhang, 2012).

The first wave of transition is configured by

the rapid transformation from a vacant industrial area to the art zone by

bordered and marginal communities (mostly young artists). Being suppressed by

the conventional age categorization and capitalist profit-making culture, the

youngsters and artists gathered around the area and established their studios

with cheap rent and ample working space at only 0.3 yuan per day (Dekker,

2011). Free and bold expressions of emotions, opinions and moaning of cultural

suppressions were exemplified through various graffiti and artworks in the zone.

Strong social bonds and sense of community have also been developed due to

their empathic connections with one another under such context (Currier, 2008).

The resistance of the marginalized groups to

dominant cultures through street culture had, indeed, caught attentions from

the state. Deeming the marginalized groups as potential risks, the government

intervened and prohibited its development through collaborations with landlord

and the owner of 798 - the Seven Stars company, for destroying posters in

exhibitions and preventing taxi from entering the zone. These responses from

the state and market, had, however, raised international attention describing

the area as “hotspot for modern Chinese arts” and initiated the second wave of

transition – from 798 Art Zone to tourist destinations (Waibel & Zielke,

2012). The state has, since then, closely collaborated with the market and attempted

to commodify and incorporate street culture back to mainstream culture for both

tourist and public consumption in a non-transgressive and non-threatening way.

The second wave of street culture

institutionalization has then elicited widespread debates from scholars and

media questioning the nature of street culture. First, strict laws regulating

the scope of public debates on socio-political issues undermine the freedom of

expression of youngsters and artists (Brunner, 2017; Zhang, 2012). Graffiti and

other artworks were not allowed to express criticism for the communist regime, thus

resulting in political self-censorship among artists (Brunner, 2017). Second,

the creative industry has also been heavily regulated and influenced by

capitalist systems. Most elements of street cultures are now only produced because

market demand exists instead of the expression of emotions or creativity. Some artwork

is excessively expensive, which deconstruct the connections of street culture

with the expression of opinions from marginalized groups (Brunner, 2017;

Branigan, 2010). A lot of artists and youngsters have to leave due to the

increased land rent in the area (Branigan, 2010).

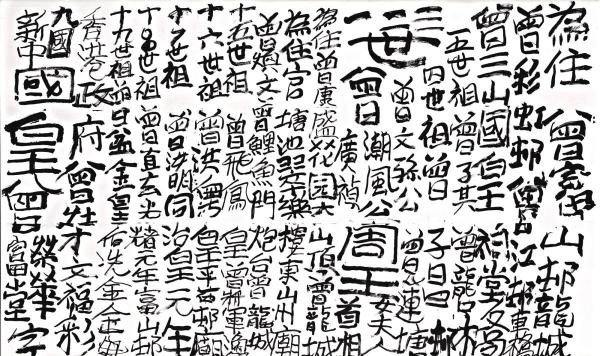

Who is the "King of Kowloon"?

The case of Hong Kong and the “King of Kowloon” also offer some great insights into the discussion of graffiti commodification. Tsang Tsou-Choi (1921-2007) is one of the most renowned artists and pioneer in popularizing urban street culture and graffiti in Hong Kong. Proclaiming himself as the “King of Kowloon”, Tsang’s work is considered as one of the “collective memories” and a crucial part of Hong Kong culture (Valjakka, 2016). His practice was provoked by his infuriation to the British colonial government for failing to recognize the rightfulness of the land and his title in the Kowloon peninsula. Despite multiple attempts in expressing his resentment, his claims were dismissed by the government due to the lack of evidence (Chang & Gao, 2012). Thus, Tsang began to mark his royal patents and decrees on the street with a mixture of black ink and paint. As a result, he was regarded as rather a calligrapher than a graffiti artist (Valjakka, 2016).

Traces of the "King of Kowloon" (Photo retrieved from Orange News/ CC BY 2.0)

From lampposts to Converse shoes: Responses from the government and the market

Tsang’s graffiti represents the cultural traces of the power struggle between dominant and marginalized classes. Owing to the illegal nature of his work, he was in frequent confrontations with the government authorities and was arrested and detained numerous times. His work was also erased wherever the police found them. Despite facing suppression from the dominant powers, Tsang continued to express his anger through calligraphy and graffiti in various places on the street ranging from lampposts, pillars and walls to cars and even other private properties. However, the government responded softly towards his repeated flagrant violation of laws and ignorance of warnings as he was rarely charged for vandalism. His graffiti can thus, as described by Chang & Gao (2012), be regarded as the “reclaiming of public space” and the accusation of state incompetence.

However, the contextual meaning of his graffiti changed significantly in recent years (Valjakka, 2016). His relentless attempts into reapplying and re-publicizing his proclaim through graffiti gained international attention from many different artists. For instance, one of his work was sold for USD$7050 in October 2004. His work is also being considered as “a signifier of a local” (Clarket, 2001, p.183). Recognizing the commercial value and importance in local identity building, both the market and the state have since then drawn attention to his work. Shortly after his death, his last surviving work in public space was acquired by the M+ museum in West Kowloon, while another one in Tsim Sha Tsui Pier was protected by plexiglass.

Nonetheless, neither of these attempts were made solely for the commemoration of Tsang’s work. Many of his work was then commodified and re-employed as souvenirs ranging from posters, stationery, mugs to even Converse shoes (“Who is the King of Kowloon?”, 2011). Started as an expression of displeasure to the government, his work has then been taken out of context and have gradually lost its colours (Ho, 2014). The commodification of his “graffiti” has then erased and neglected the core values of street culture as a representation of voices from the suppressed and marginalized.

Summary

Graffiti and street culture illustrate the key concept of borders in cultural geography. Conventional categorization of individuals may create borders for marginalized classes and culture such as youngsters, who belong neither to “adult” nor “child”. These mainstream cultures have then marginalized the youth and drive them to establish their presence through street culture. The struggle of power between mainstream and marginal classes may also (re)shape the spatial extensions of other bordered cultures. While we are often concerned with whether the value of graffiti as a street culture may be undermined by its commodification or institutionalization, this page takes a step back to consider why graffiti would be created in the first place. Graffiti can be a sign that some social groups or people feel that they are underrepresented in the mainstream culture – they resort to graffiti as a means to counteract the mainstream, or to de-border. With this understanding in mind, a more important question for us to consider is how the demands from the graffiti-makers can be addressed.

Reference

Anderson, J. (2010). Understanding cultural geography: places and traces. Routledge.

Branigan, T. (2010, February 24). Beijing artists say development is driving them out. Retrieved July 14, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/feb/24/beijing-chinese-artists-studios-evictions

Brunner, E. (2017). Imagining China through the culture industries: The 798 art zone and new Chinas. In Imagining China: Rhetorics of Nationalism in an Age of Globalization (pp. 339-369). Michigan State University Press.

Chang, Z., & Gao, C. (2016). Graffiti Hong Kong: Public space, politics and globalization. Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong Press.

Clarke, D. (2001). Hong Kong Art. Culture and Decolonization. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Cresswell, T. (1996). In place/out of place: Geography, ideology, and transgression. Minneapolis, Mn.: University of Minnesota Press.

Currier (2008). Art and power in the new China An exploration of Beijing’s 798 district and its implications for contemporary urbanism. Town and Planning Review, 79 (2/3), 237-265.

Dekker, R. (2011). 798 ART ZONE BEIJING Site of ‘Cultural Revolution’ or Showpiece of City Marketing?

Nandrea, L. (1999). Graffiti Taught Me Everything I Know About Space’: Urban Fronts and Borders. Antipode, 31(1), pp. 110–116., doi:10.1111/1467-8330.00094.

Turner, V. (1982). From ritual to theatre: The human seriousness at play. New York: Performing Arts Journal

Valjakka, M. (2016). Contesting transcultural trends. Emerging self-identities and urban art images in Hong Kong. In Routledge handbook of graffiti and street art. London: Routledge.

Who is the King of Kowloon? ArtisTree exhibition pays tribute to artist and eccentric Tsang Tsou-choi. (2011, April 05). Retrieved July 14, 2020, from https://artradarjournal.com/2011/05/04/who-is-the-king-of-kowloon-artistree-exhibition-pays-tribute-to-artist-and-eccentric-tsang-tsou-choi/

Zhang, Y. (2012). 艺术・商业・政治: 北京798艺术区的前世今生 [Master of Philosophy dissertation, Chinese University of Hong Kong]. Retrieved from: https://repository.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/tc/item/cuhk-328441