1. Introduction

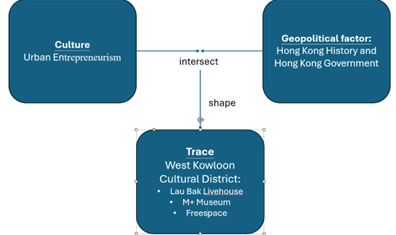

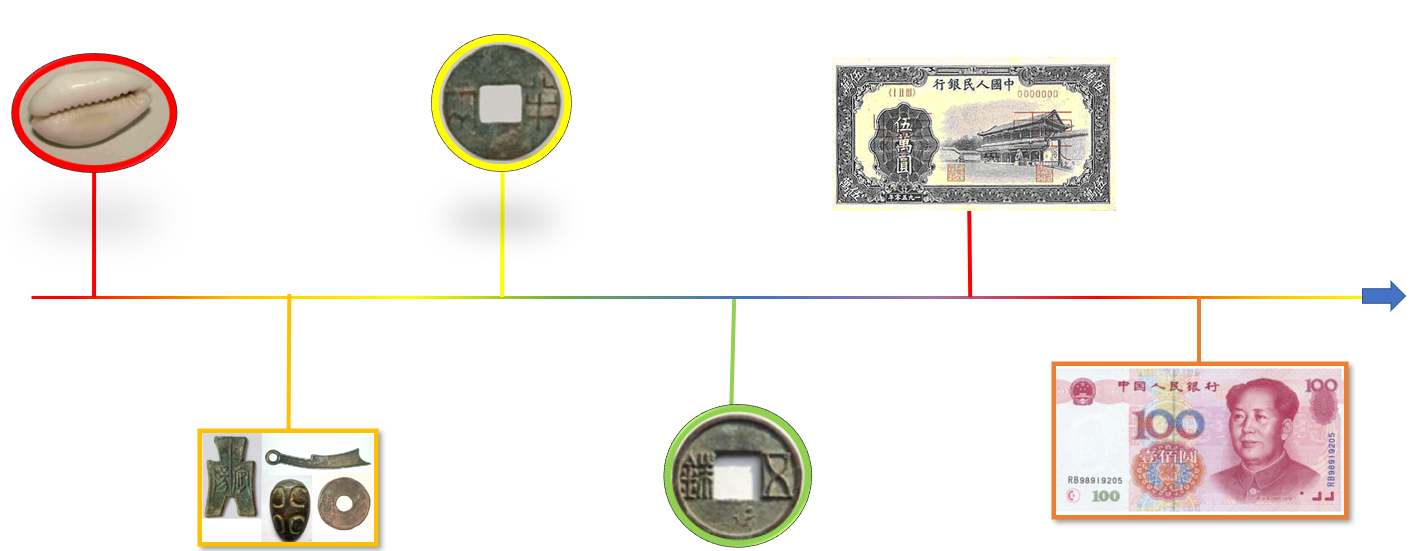

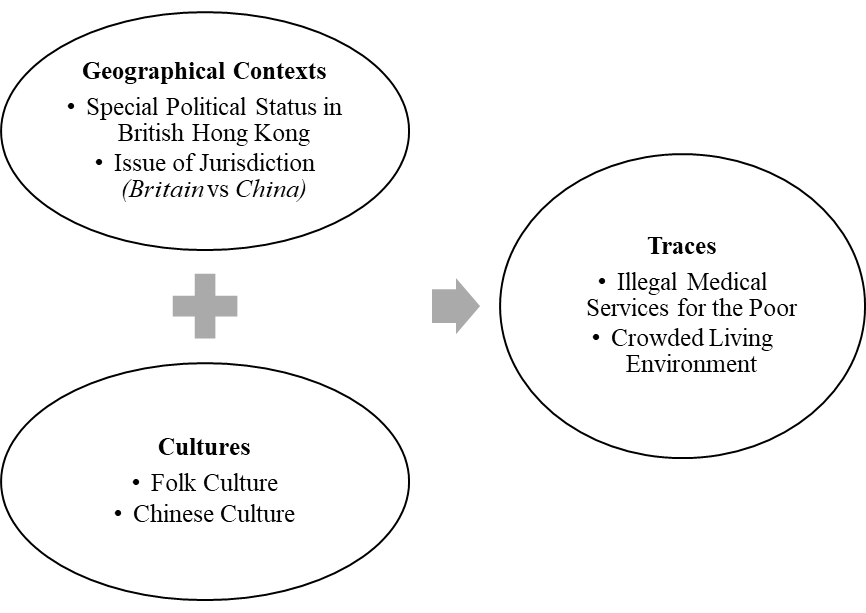

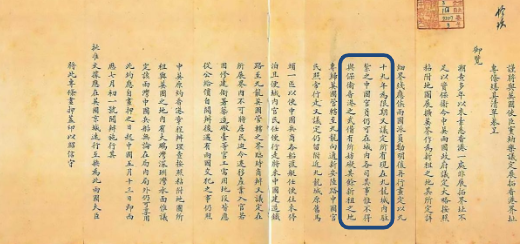

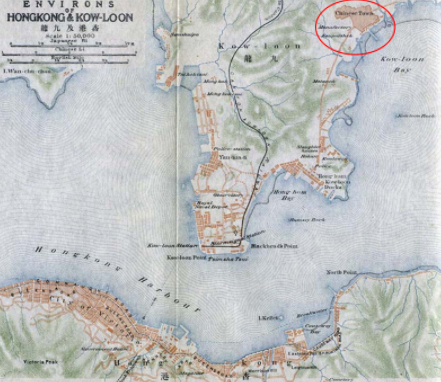

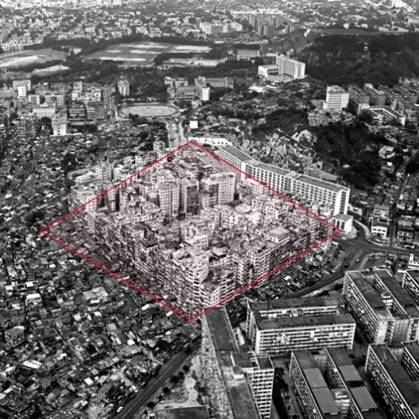

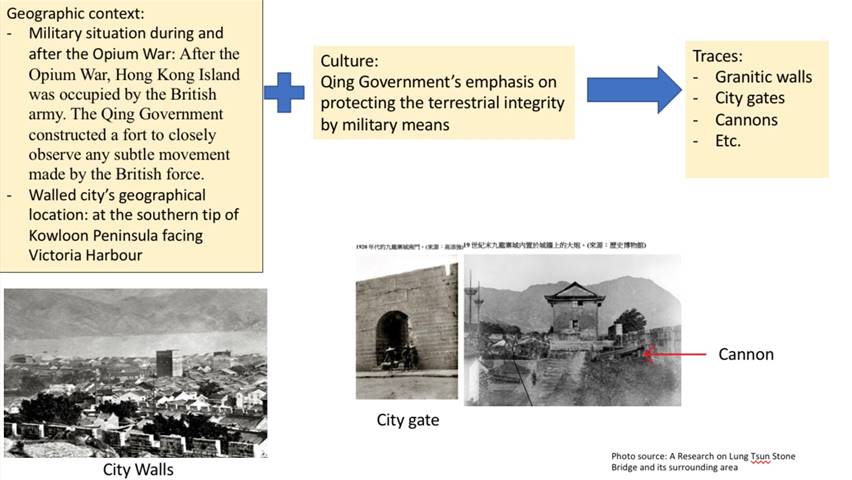

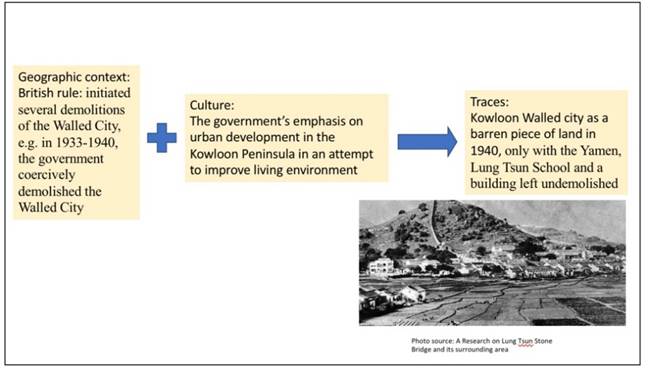

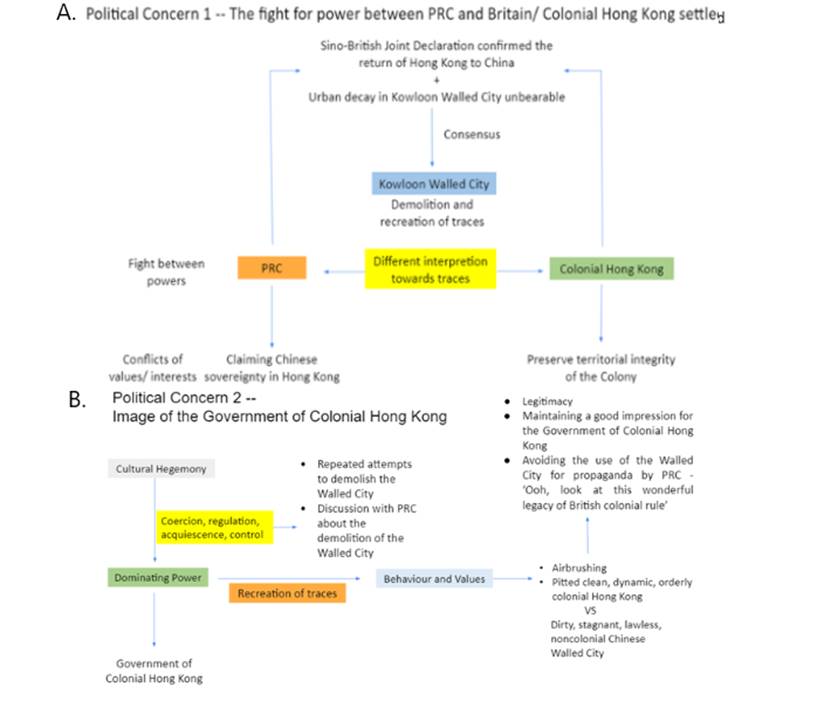

This project examines the historical transformation of Kowloon Walled City from a Qing military outpost into a densely populated “ungoverned” enclave and, eventually, its clearance in 1993–94. The phenomenon deserves attention because it condenses wider tensions between state authority, capitalist urban development and everyday survival strategies of marginalized residents in a tiny piece of urban space. We treat Kowloon Walled City as a cultural trace: a material and symbolic outcome of how ambiguous sovereignty, refugee inflows and informal economies interacted over time. Geographically, the case is shaped by its liminal position between British Hong Kong and mainland China, chronic housing shortage and weak formal governance. Culturally, it is rooted in Chinese clan networks, triad organizations and a strong sense of belonging. Analytically, the project draws on cultural geographical concepts of place, sense of place, social norms, economy–culture relations and hegemony to link geographical context, culture and this urban enclave.

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

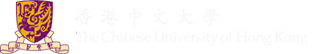

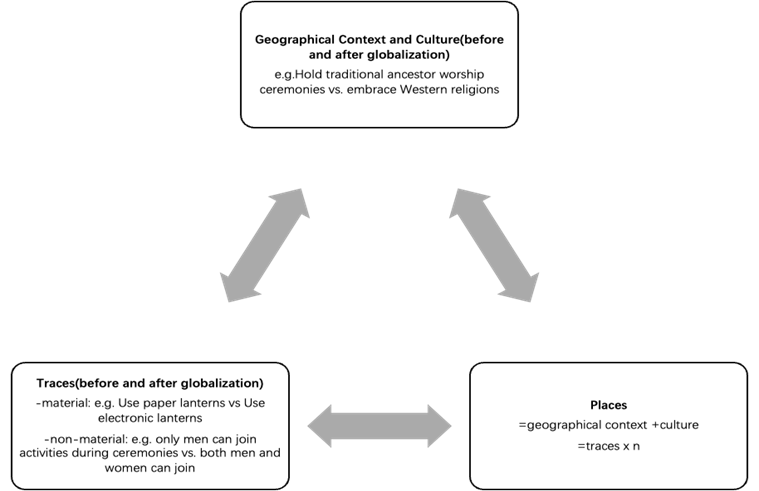

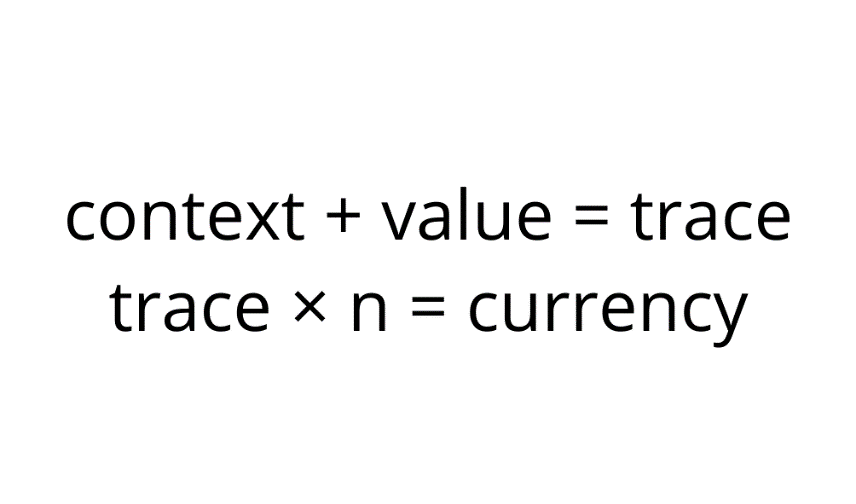

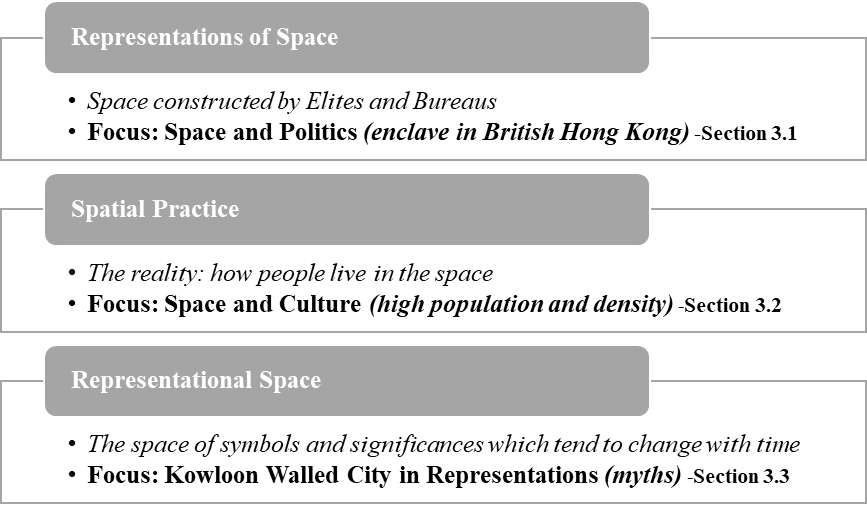

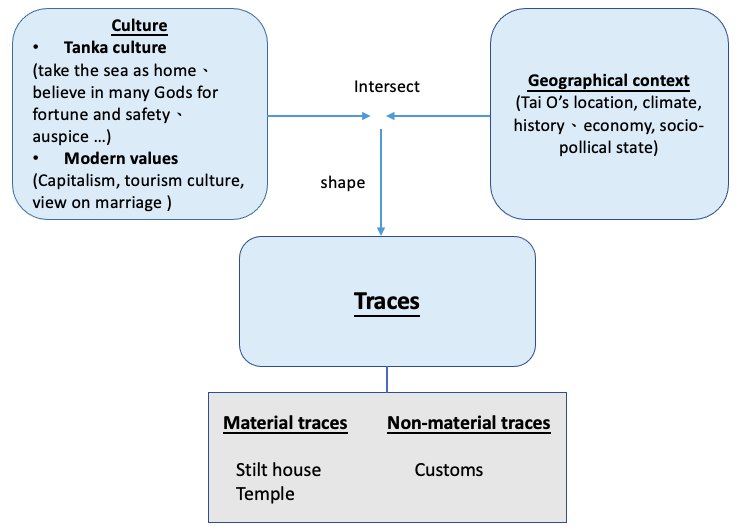

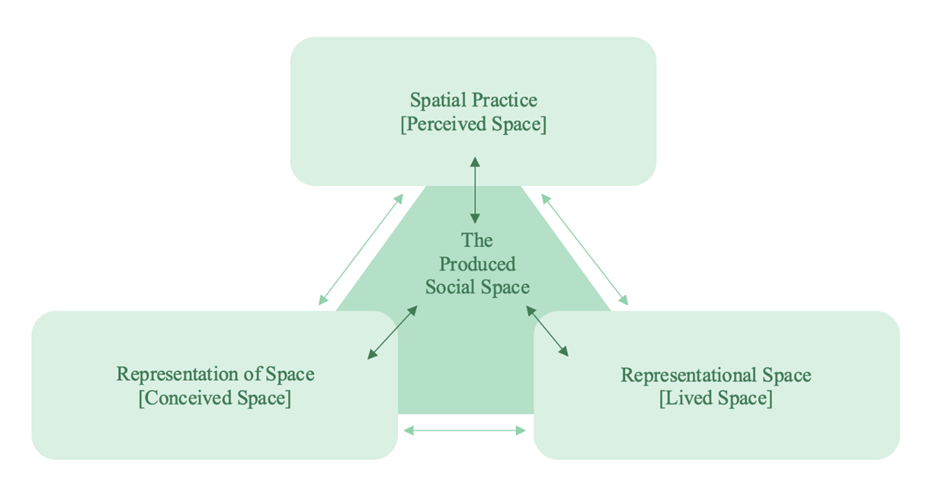

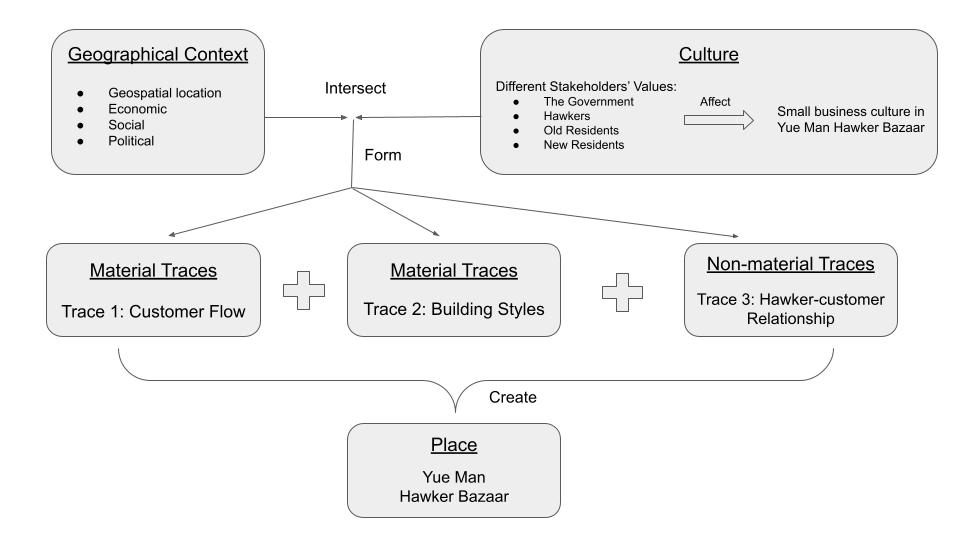

Geographical perspective states the rules, norms and physical features of a specific place, and cultural perspective states the common values and attitude of the people in the place. Cultural geographical perspective is an intersection of geographical and cultural perspective, accounting for both material and non-material traces. Hence, the perspective is to explain the formation of geographical features with cultural perspective, and vice versa.

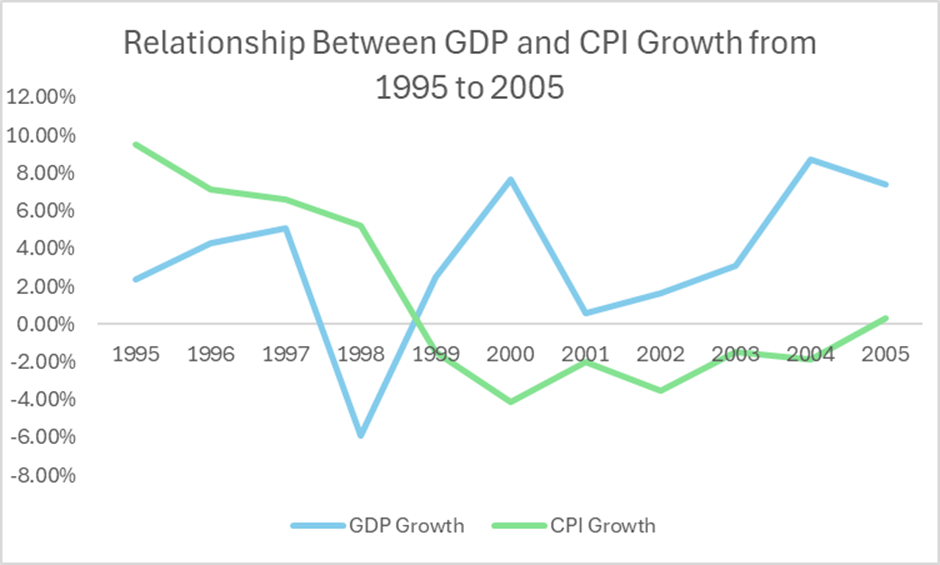

“History forms social norms” is one concept to be discussed in the analysis, social norms refer to both the self-identity of individual, and common values, memories of the people in the place. History provides common memories to the society, and shows consequences of choices that have been made (Significance of History for the Educated Citizen | Public History Initiative), providing common values and responsibility to individuals.

“Economy and culture are closely related” is another concept to be discussed, when researching people's values in the place, historical economic data plays a huge role in explanation, evidenced by the poor economic conditions post WW1 induced Germans into valuing Nazism (Aftermath of World War I and the Rise of Nazism, 1918–1933 - United States Holocaust Memorial Museum).

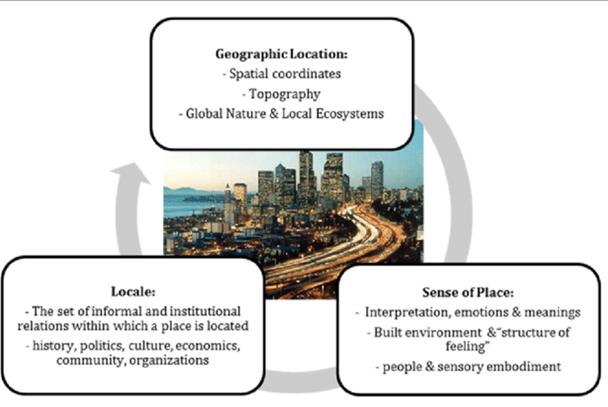

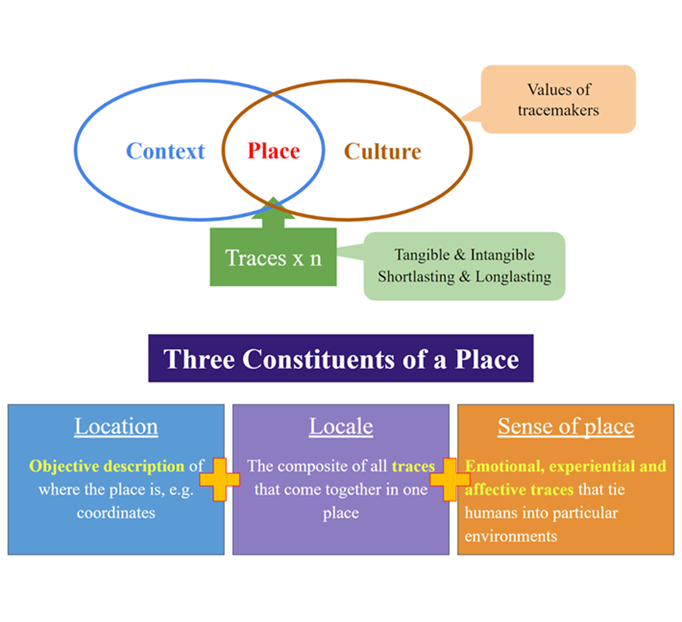

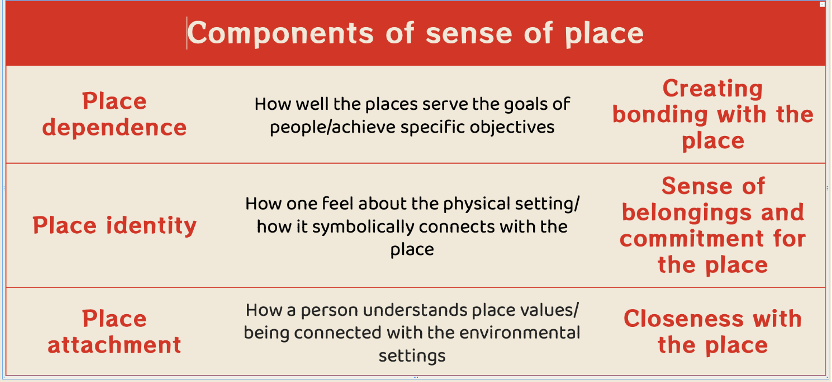

The concept of “Three constituent parts of place” will be analyzed. It shows how a “space” can become a “place” by fulfilling location(the coordinate), locale(the environment both natural and historical) and sense of place(social connection to the place). The history of how the locale and sense of place is formed will be discussed in the following research.

The concept of “Sense of belonging” is hinted as a force of cultural purification, in which local cultures are accepted while foreign cultures are rejected.

The concept of “Dominating power and hegemony” is applied in the research. Dominating power can be government, foreign countries or community. New power tends to alter the place’s norms to create new values to stabilize their powers, as evidenced by Hitler turning German’s frustration from unemployment to Jews and other races (From Citizens to Outcasts, 1933–1938 - United States Holocaust Memorial Museum).

The history of Kowloon Walled City’s original military position forms the locale of the place and explains part of the social norms, in which the constituent parts of place explain how Kowloon Walled City becomes a place. Economic factors shape social norms, and sense of belonging shows resistance to change in norms. In which social norms explain how Walled City became a criminal haven.

3. Empirical Analysis

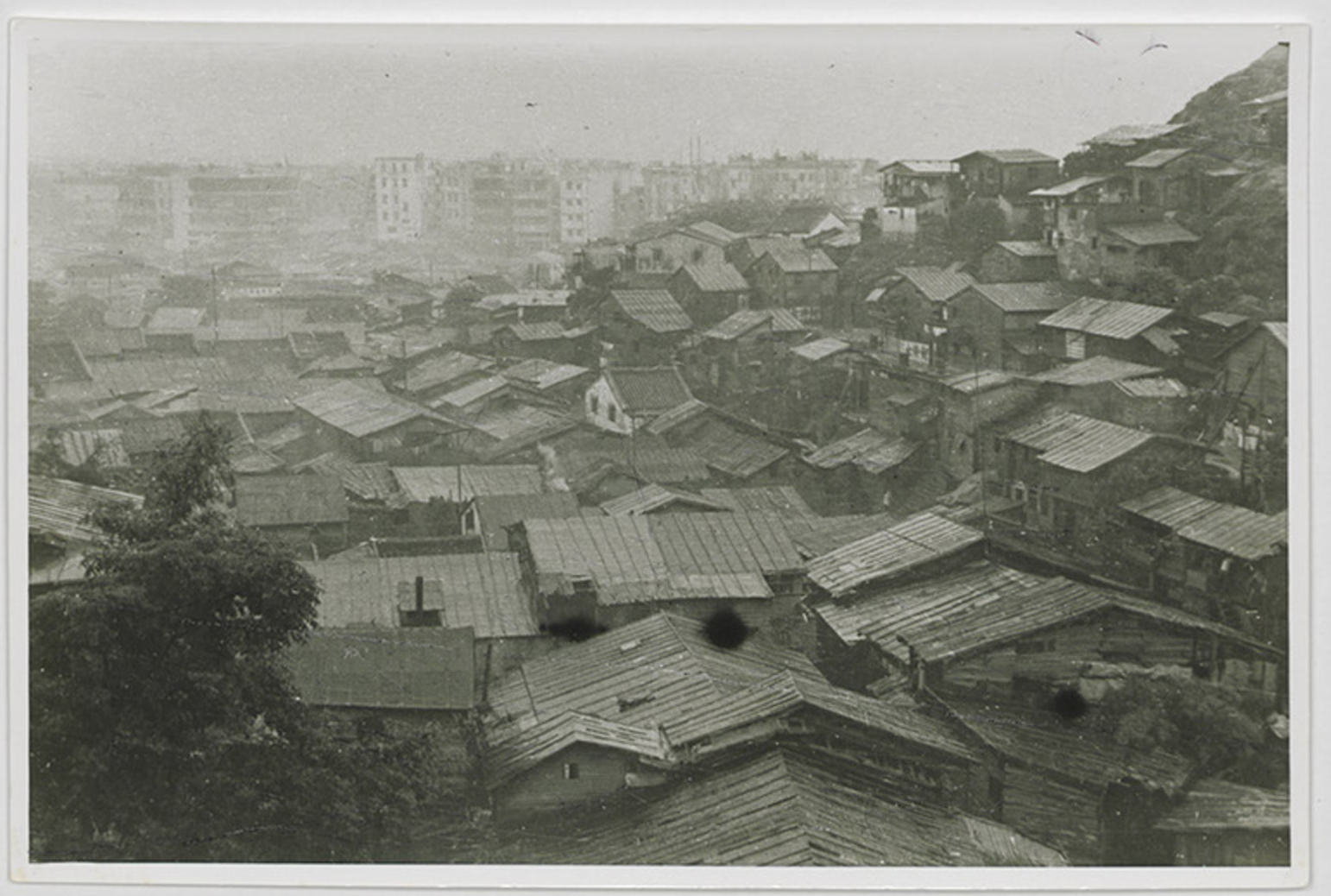

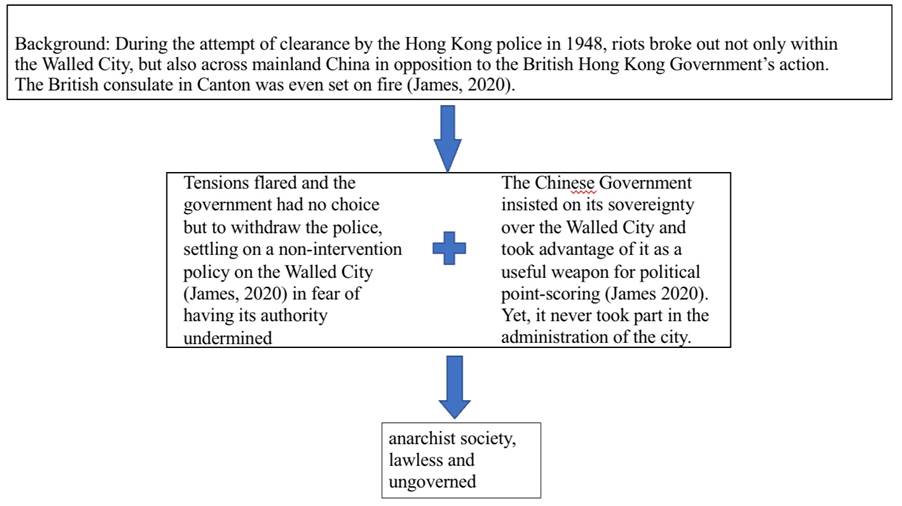

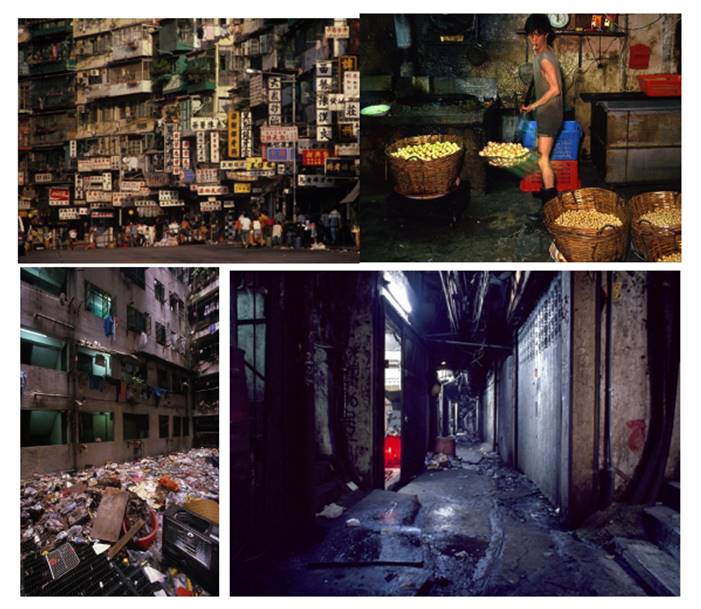

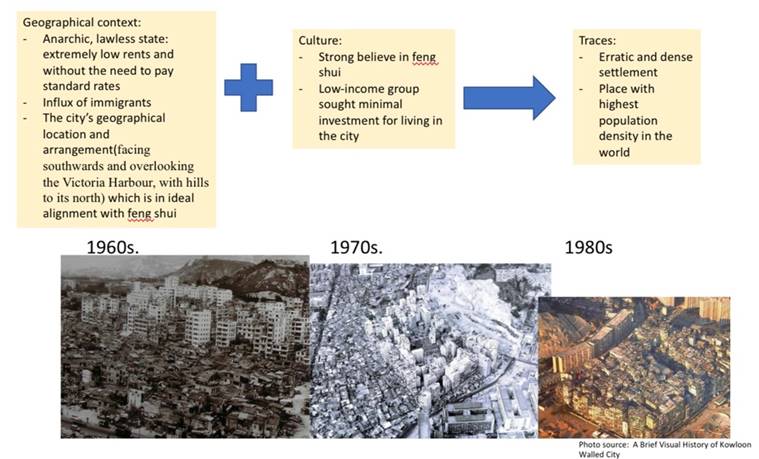

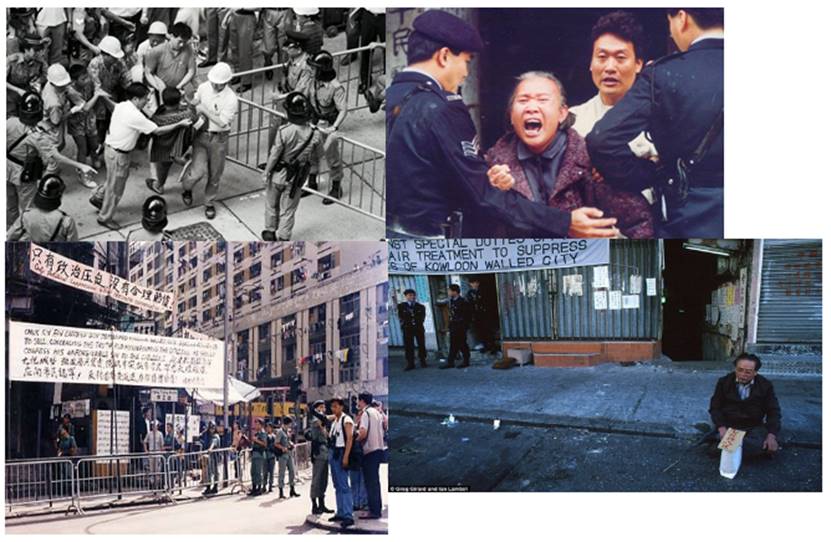

In the past, Kowloon Walled City was a densely populated, ungoverned urban area, filled with a mixture of culture and people in the area. Kowloon city was an area that is already a populated area itself. This historical place’s sovereignty is quite ambiguous with its historical treaties (Girand & Lambot, 1993), hence it creates an environment that cannot be ruled by any governing body, allowing multiple job opportunities in the grey area of the law, such as unlicensed doctors, prostitution, and even gambling (Fraser & Li, 2017). Although this seems to shine a very negative light on the area, there is another side to the city. The City’s dense population allow words to spread through the neighborhood quickly, creating a sense of order among each other in order not to be bullied by the rest of the neighbors. People in turn, created their own social law without official authorities (Sinn, 1987). If argument were to break out, situation would mostly dominated by local triads and informal networks, rather than official state power.

However, the City’s geography became a symbol of defiance. The reason for more people coming into the city and why local triad were in power is that refugees, migrants, and those seeking to escape the reach of formal law seek shelter in the Walled city due to it being an ‘ungoverned’ part of Hong Kong (Wesley-Smith, 1973). People with a degree of knowledge, skill, or capital can easily set up their business as it is still an easily accessible part of Hong Kong. Due to the convenience in location, materials can easily be transported into the area and there is also populated area outside the walled city. People with less resource then tends to join local triads in order to make a quick living (ALSuwaidi et al., 2024).

Another geographical factor of why Kowloon walled city has such diverse culture is that Hong Kong is near China. Back in the civil wars days, many Chinese people flee to Hong Kong in order to escape the war between the Nationalist party and the Communist party (Fraser & Li, 2017). However, as Hong Kong has law with refugees and officials doesn’t take in people unlimitedly, people started smuggling into Hong Kong. As smugglers are illegal immigrants, they need the shelter from Kowloon Walled City in order to stay in Hong Kong, away from the war in mainland.

The triads’ control over gambling, prostitution, and protection rackets, whereas family or clans will take up a more usual day to day aspects of the economy such as food and retailing, creating Kowloon Walled City’s own underworld culture.

As there was overcrowding and lack of infrastructure. Residents built and modified their homes with little regard for official regulations, creating a unique architectural landscape. This grassroots urbanism reflected a collective resistance to external control and a pragmatic approach to daily life, creating the culture of grassroots urbanism in an unique area of the vibrant and modern Hong Kong (Wesley-Smith, 1973).

Situated within Hong Kong but distinct from its regulated urban environment, the Walled City developed a hybrid identity. Residents navigated between Chinese traditions and the cosmopolitan influences of Hong Kong, resulting in a cultural blend that shaped local norms, values, and attitudes toward authority. This hybrid identity culture gives the residents a deeper sense of belonging to their turf and therefore they were often very strong and united against external powers trying to use their city as a place for external use.

The most obvious issue was the mess of no official control. Fraser & Li (2017) said those unofficial businesses ran wild: some people set up “clinics” without being real doctors, and houses were built however people wanted—some had three floors stacked on top of a tiny shop, with no windows or fire exits. It was a world away from Hong Kong’s clean, regulated streets, and it put people in real danger. There were also fights over power: the rules from clans and triads often clashed with the Hong Kong government’s orders. Worse, most people there were left out of Hong Kong’s basic help—they couldn’t go to public hospitals for cheap or send their kids to regular schools, which made the gap between them and other Hong Kong residents even bigger.

These problems finally made things shift. Between 1993 and 1994, the government tore down the Walled City. It was a clear sign that a “place with no rules” just couldn’t exist in a modern city—so the area started following official laws, with proper houses and shops built later. But something else changed too: people stopped seeing the Walled City as just a “bad spot.” Its jumbled, self-built houses and the way neighbors stuck together became part of Hong Kong’s history. That mix of Chinese traditions and Hong Kong culture even showed how diverse Hong Kong really was. It also made people think differently about managing cities—clans and triads had kept a crowded community from falling apart, which made officials realize that local groups could help too. Later, when building new neighborhoods, some officials asked residents to join in planning—something they might not have thought of without the Walled City’s example.

4. Conclusion

This project shows that Kowloon Walled City was a cultural trace of the interaction between a liminal geopolitical position, refugee-driven urban pressure and Chinese cultural institutions such as clans and triads. Using a cultural geographical perspective on place, sense of place, social norms and hegemony allows us to link its extreme built form and informal economy to deeper histories of ambiguous sovereignty, housing scarcity and grassroots self-governance. The concepts of “history forms social norms” and “economy–culture relations” are particularly useful for explaining why the City became both a criminal haven and a tightly knit community. However, they need to be complemented by attention to state power and demolition policies to capture later transformations. Our findings suggest that contemporary urban policy should recognize local networks as potential partners in governance while avoiding the neglect and exclusion that produced such extreme environments in the first place.

References

Aftermath of World War I and the Rise of Nazism, 1918–1933 - United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (n.d.). https://www.ushmm.org/learn/holocaust/aftermath-of-world-war-i-and-the-rise-of-nazism-1918-1933

From Citizens to Outcasts, 1933–1938 - United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (n.d.). https://www.ushmm.org/learn/holocaust/from-citizens-to-outcasts-1933-1938

Fraser, A. & Li, M. (2017). Underworld and Order: The Social Ecology of Kowloon Walled City. Hong Kong University Press. https://www.hkupress.org/

Girand, P. & Lambot, J. (1993). Sovereignty Ambiguity in Historical Treaties: The Case of Kowloon Walled City. Journal of Hong Kong Studies, 8(2), 45-62. https://www.jhks.hku.hk/

Significance of History for the Educated Citizen | Public History Initiative. (n.d.). Public History Initiative. https://phi.history.ucla.edu/nchs/preface/significance-history-educated-citizen/

Sinn, E. (1987). Informal Governance in Unregulated Zones: Clans and Triads in Kowloon Walled City. Modern China, 13(3), 321-340. https://journals.sagepub.com/home/mcx

Wesley-Smith, P. (1973). Refugees and the "Ungoverned Zone": Kowloon Walled City 1949-1970. Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, 5(4), 38-45.http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/serial?id=bcas

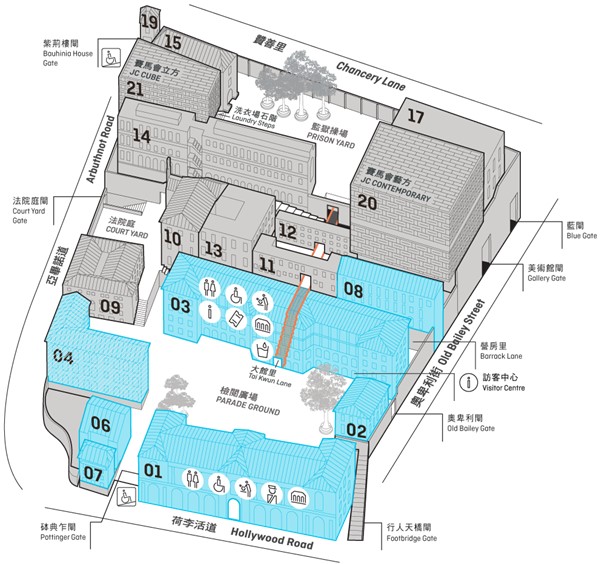

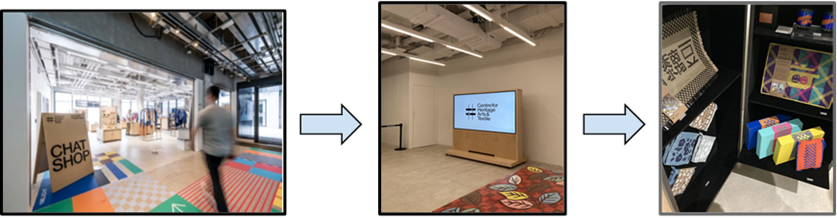

1. Introduction

The Historic Centre of Macao, as one of the oldest and largest existing architectural complexes in China that blends Eastern and Western cultures, offers a unique subject of study for exploring colonial history and culture through its continuously evolving spatial form and cultural landscape. The Historic Centre of Macao embodies the dynamic balance achieved by East Asian and European civilizations through spatial practices over four centuries. If this area is viewed as a cultural trace, its street layout, the juxtaposition of religious buildings, and the forms of residential architecture are texts reflecting the mutual permeation of Eastern and Western aesthetic concepts, power relations, and daily life. The formation of cultural traces is influenced by Macao's unique geographical location, the governance model during the colonial period, and the socio-economic structure shaped by trade. Following its 1999 return to China, this cultural landscape has entered a new phase. Its preservation is now framed within a national narrative of "One Country, Two Systems," Macao's ongoing role as a global cultural bridge within a unified China.

This article seeks to underline the political forces that have shaped Macau’s landscape, focusing on the Historic Centre of Macau and its gambling industry, and covers the Portuguese colonial authorities, the Chinese central government and the government of Macau SAR.

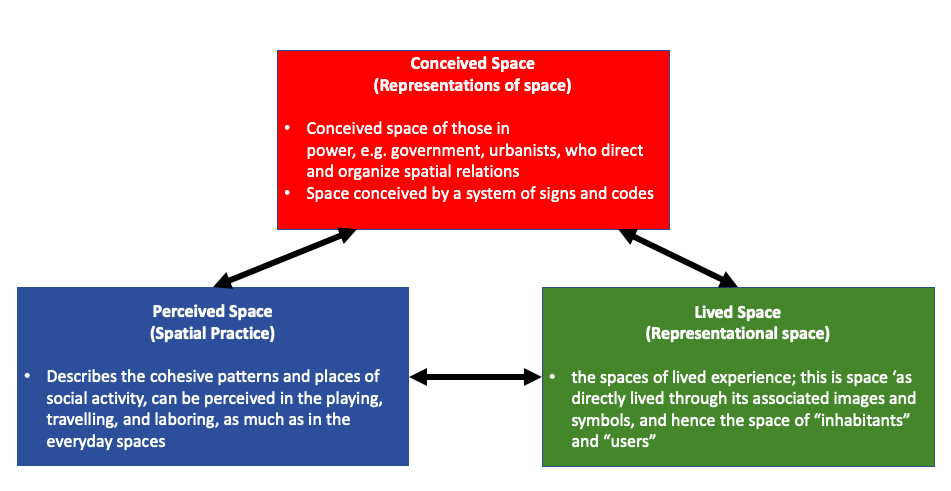

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

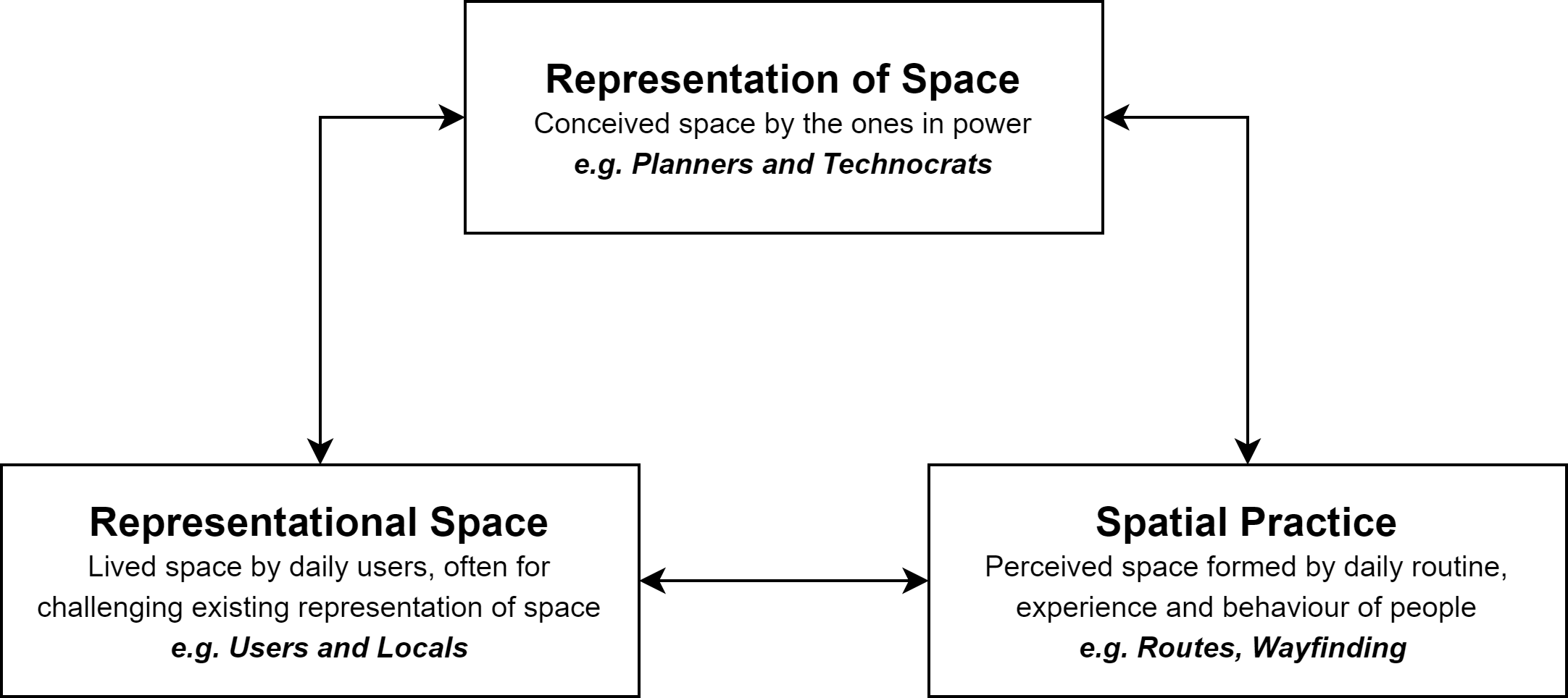

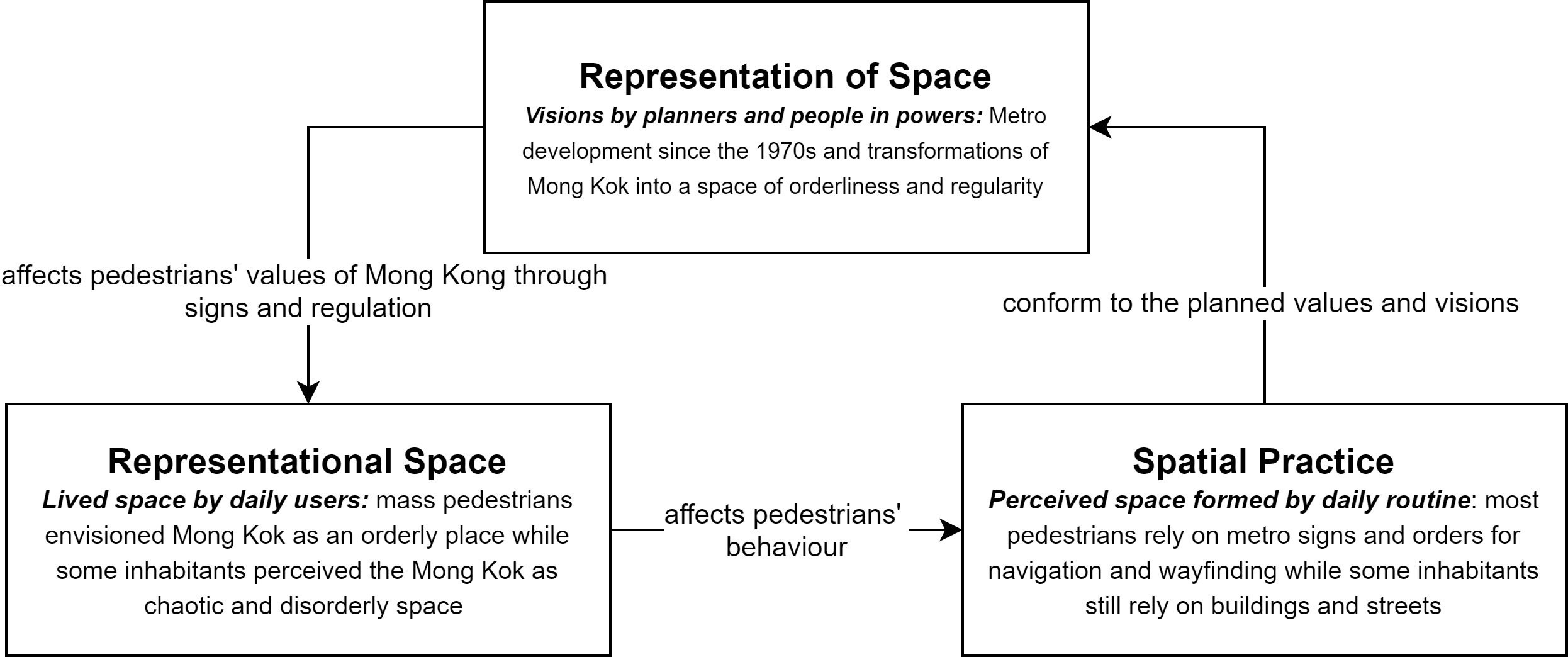

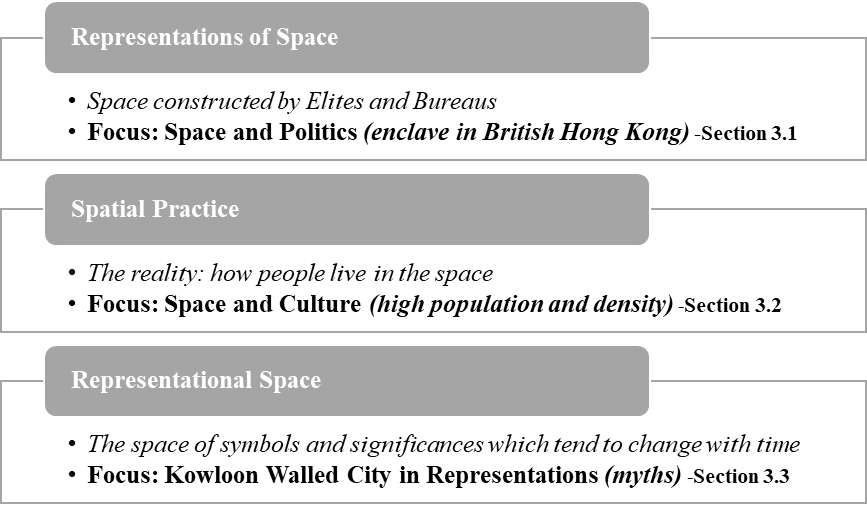

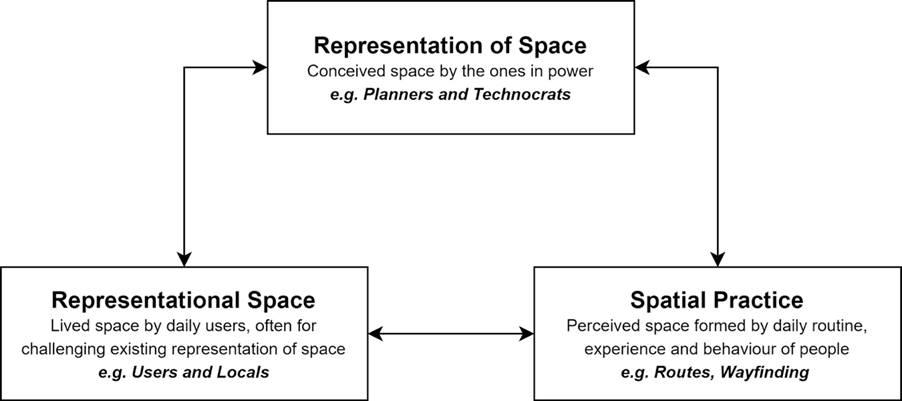

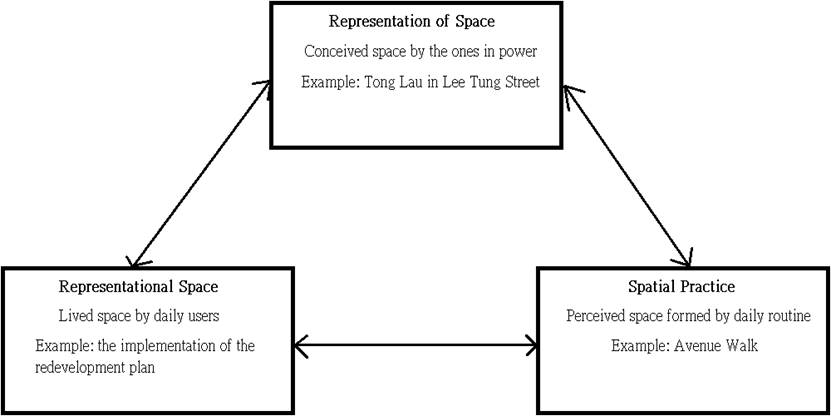

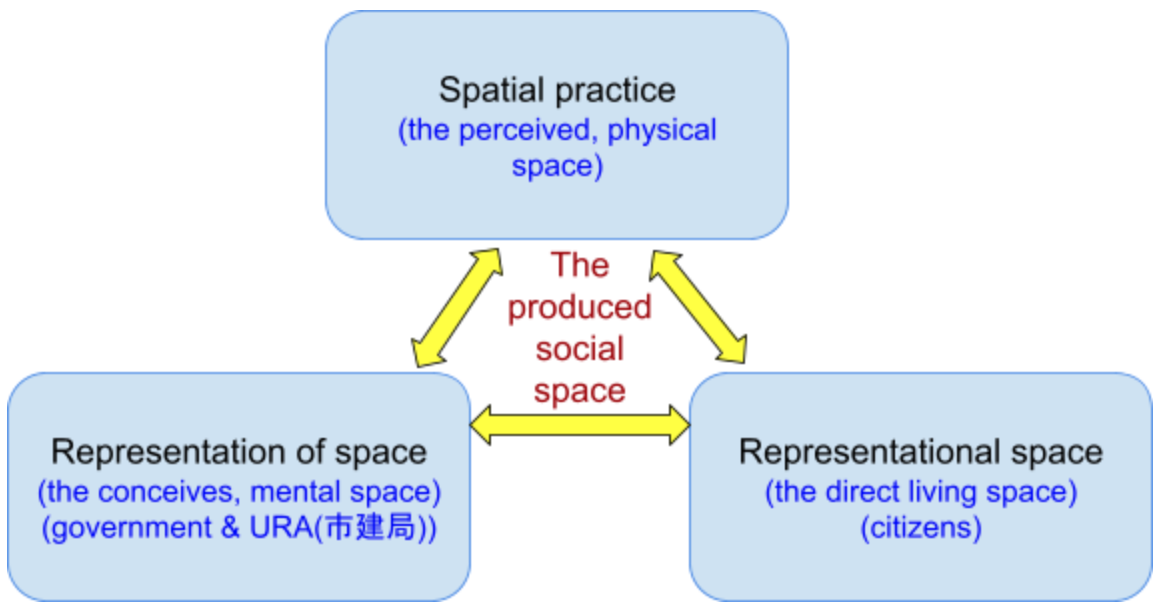

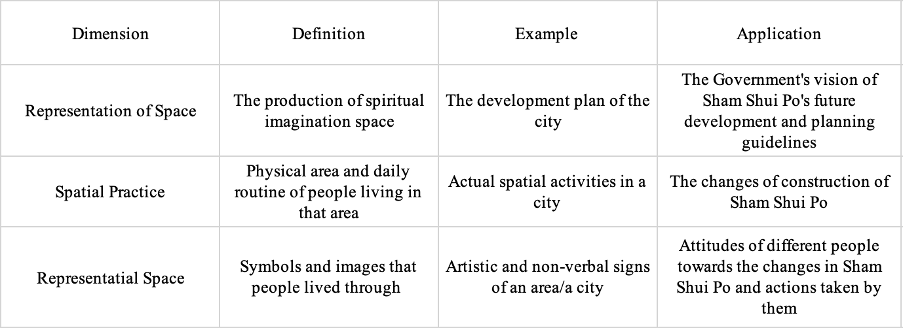

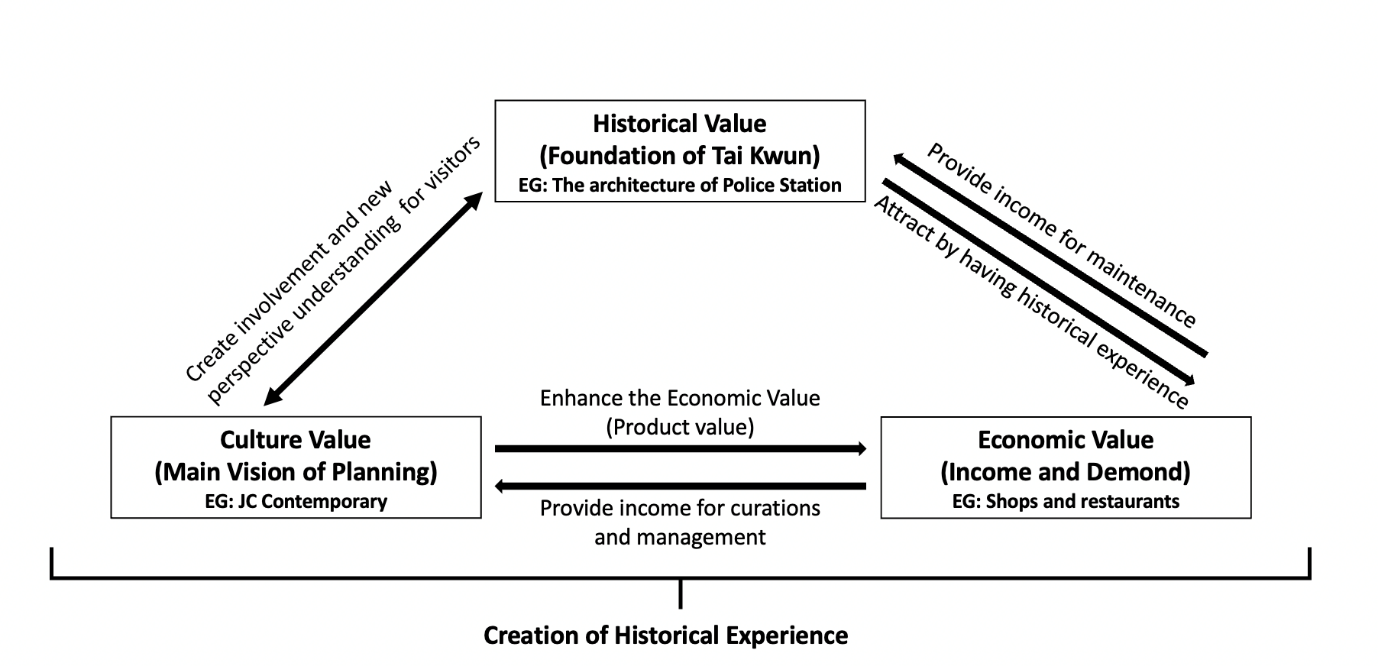

According to the theory of representation of space by Lefebvre, power holders, such as the government, would create places. (Lefebvre, 1974/1991) For example, in the case of Portuguese Macau, colonial government’s policies shaped Macau into a town of divine presence and worldly temptation at the same space. Also, the theory of spatial practice stated the actual use of space reflect the social structure and the pattern of daily life. In Macau, the gambling industry and the heritages created huge employment and routines, and numerous hotel casinos were established, generating substantial revenue for the government which affected the social structure and pattern of Macau heavily, this can clearly explain the theory.

3. Empirical Analysis

Portuguese Macau: Divine Presence and Worldly Temptation

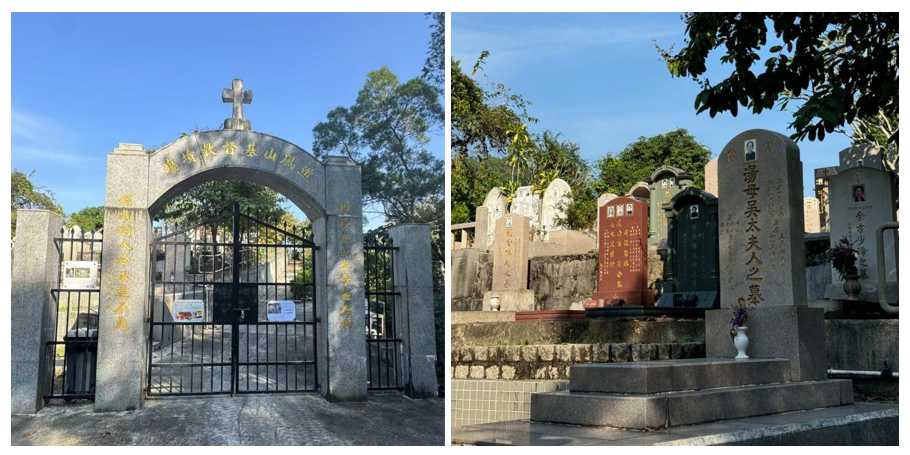

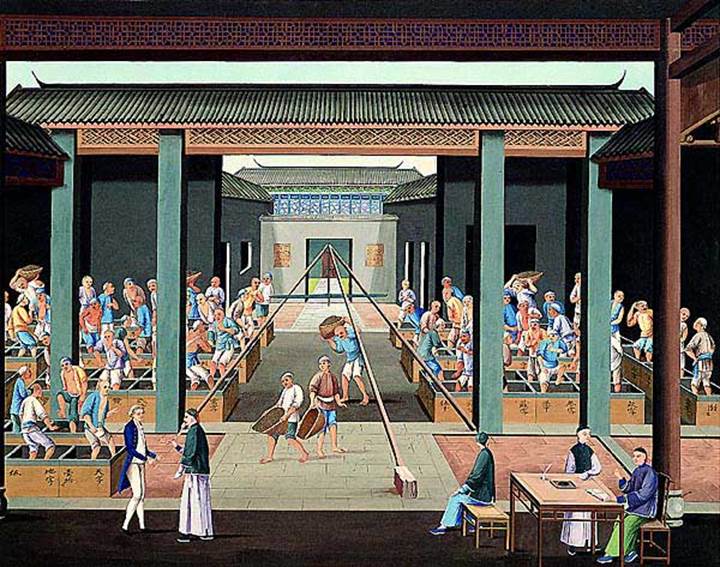

The history of the Historic Centre of Macau can be traced back to the period of Portuguese rule. During the Portuguese colonial era, Macau’s urban area had a strong Catholic atmosphere; however, Macau’s gambling industry also began during this period. Therefore, a curious phenomenon of the coexistence of the sacred and the secular occurred in Macau.

Firstly, Macau was a town with strong Catholic atmosphere. In today’s Historic Centre of Macau, Igreja de Santo António, Igreja de Santo Agostinho and Seminário e Igreja de São José are still cultural heritage sites. As Portugal was a traditionally catholic nation, her colonial empire also centered around the Catholic Church, which could explain the many Catholic institutions present in Macau. In fact, the town itself was closely associated with missionary activities. Matteo Ricci and Robert Morrison also came to Macau to spread the Christian religion. As a result, Macau was praised as “Cidade do Santo Nome de Deus de Macau, Não Há Outra Mais Leal,” which can be translated as “City of the Holy Name of God of Macau, there is none more Loyal.” (胡鸝藻與許貝文,2023,頁68)Therefore, Macau has strong connections with Catholicism and the Christian religion, even God Himself.

Figure 1: Seminário e Igreja de São José (Filmed by the author, 22/11)

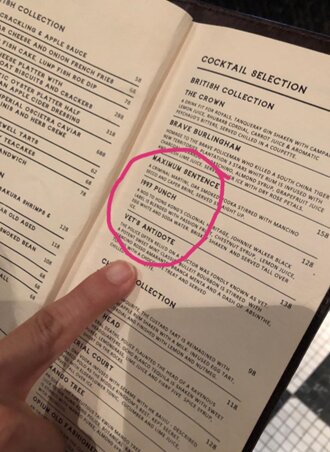

Nevertheless, Macau is also known for its gambling industry. In 1847, the Portuguese colonial authorities legalized gambling. In 1864, the government even officially promoted and taxed the industry. These measures greatly fostered Macau’s gambling industry as well as significantly increased government revenue. In the 1870s, there were around 200 gambling houses in the town. As aforementioned, Portugal was a Catholic nation and she would have reservations about, even discourage the gambling industry. In fact, the Portuguese government herself banned gambling in 1896. However, interestingly, Macau did not follow suit and granted patent to the gambling house. The reason behind was most likely that the industry produced great revenue for the colonial government and boosted the economy. In 1911, the Portuguese governor acknowledged that without gambling industry, Macau would be in a serious crisis. From 1937, taxes from gambling house became the largest source of revenue for the colonial authorities. Moreover, in 1961, the Portuguese government decreed that Macau was a tourist site and granted special permission to the gambling industry. From that time on, gambling industry in Macau was completely legalized and acknowledged by the metropolitan Portuguese authorities.(徐永勝,2000)As a result of these historical developments, Macau became a town of worldly temptation, “The Monte Carlo of the East”.

Political forces significantly shaped the town landscape of Portuguese Macau. Portugal was a Catholic nation, and they built churches and monasteries in the town. As a result, there is a religious aura in Macau even until now. However, by the 19th century, as the colonial government’s needs for revenue grew, Macau started to develop its gambling industry, turning the town into a worldly temptation for people around the world. Therefore, political forces shaped Macau into a curious mixture of a divine and worldly town at the same time.

Chinese Communist party (CCP) in Macau: political and economic forces

In terms of heritage culture in Macau, these areas being used after handover to China. The central government has redefined Macao's cultural role, emphasizing its role as part of Chinese culture and positioning it as "an important window for the exchange and mutual learning between Chinese and Western civilizations". Beijing tried to be diminishing local characteristics. Senior cultural workers have pointed out that Macao's unique Chinese and Western cultural characteristics have not been valued or maintained since the handover of sovereignty and are being weakened. As usual, official discourse emphasizes that Chinese culture is the lifeblood of Macao and promotes Chinese culture through various cultural activities and education to counteract the cultural influence left over from the colonial period. Macau's education authorities are actively utilizing spaces in the Historic Centre to promote patriotic education. The Macau Museum, under the Cultural Affairs Bureau, has launched guided cultural tours in the Historic Centre to deepen public understanding of Macau's modern history and culture and cultivate patriotism. Nowadays, government encourage teachers to use the Historic Centre as a teaching resource to inspire their patriotism and national pride. It is clearly aimed to serve the ideology of the Chinese nation and to downplay the colonial history.

Macao SAR Government: Polices that created the appearance of two different culture

In 2001, the SAR government enacted Law No. 16/2001, which liberalized the gaming industry. It aligned with the Macau SAR government's policy direction of "establishing the tourism and gaming industry as the leading sector, with the service industry as the main body, and promoting the coordinated development of other industries. " Under the influence of this policy, Macau gradually developed its image as a "gaming city." During this period, underground industries such as prostitution and drugs also rapidly expanded, transforming Macau into a city of extravagance and decadence. Macau is a city of desires and lavish indulgence. Beneath its dazzling exterior, it is often a place that leads people astray, where one can easily find themselves trapped in dire circumstances.(自由時報 劉慶侯/特別報道 2005)

At the same time, the Macau government has also been committed to transforming Macau into a diversified leisure and tourism city. In 2005, the Historic Centre of Macau was officially inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Furthermore, in 2014, the Macau government passed the "Cultural Heritage Protection Law" to preserve historically significant buildings and sites, such as the Ruins of St. Paul's, A-Ma Temple. These cultural heritage sites embody the religious and architectural characteristics of both Eastern and Western cultures. Macau attracts numerous tourists with its streetscapes reflecting cultural integration, thereby forming the unique cultural landscape seen in Macau today.

Figure 2: A-Ma Temple (Filmed by author 23/11)

Figure 3: The Ruins of St. Paul's (Filmed by author 23/11)

Figure 4: Casino Grand Lisboa (Filmed by author 23/11)

Macau's culture is both historical and unique, serving as a model of the fusion and interaction between Chinese and Western cultures. Cultural endeavors in Macau are primarily privately run. Its distinctive blend of Chinese and Western cultures is unparalleled worldwide(錢朝陽, 孫金灧 上海大學學報: 社會科學版, 15-20, 1999).

In recent years, as the government plans to promote diversified development, reduce dependence on the gaming industry, and build a cultural capital, the Macau government has vigorously promoted the cultural and creative industries and preserved the historic district to cultivate Macau's image as a city of diverse cultures. This shift in development direction has allowed Macau to simultaneously embody the luxury of a gaming city and the cultural ambiance of history.

4. Conclusion

This report demonstrates how a cultural geographical perspective reveals the profound links between political power, economic context, and cultural formation in Macau's urban landscape. By applying Lefebvre's theory of the "representation of space," the analysis illuminates how the dominant power holder (CCP), strategically produced a space that simultaneously embodied nationalism and worldly temptation. This was not a spontaneous cultural development but a calculated spatial strategy to reconcile Chinese identity with fiscal necessity. The resulting coexistence of churches and gambling houses is a direct cultural trace of this colonial logic. Following the 1999 return to China, this dynamic has persisted and intensified, with the gambling industry's expansion now framed within a new nationalistic context of economic contribution to the CCP. To manage this unique heritage, policy should focus on zoning regulations to protect the sanctity of religious sites from commercial encroachment and promote critical heritage education that interprets this juxtaposition not as a contradiction, but as an authentic narrative of Macau's complex historical geography. We can see how the power holder constructed a space in Macau by using urbanisation and heritage interpretation.

References

胡鸝藻與許貝文(2023)。見證澳門 : 22個故事,澳門歷史城區地標為你娓娓道來。澳門:澳門人出版有限公司

徐永勝(2000)。澳門經濟概論。澳門:澳門基金會/虛擬圖書館電子出版。https://www.macaudata.mo/macaubook/ebook006/html/index.htm

澳門博彩監察協調局。https://www.dicj.gov.mo/web/cn/history/index.html

劉慶侯 (2005年4月18日)。〈澳門,賭色的慾望城市> 。《自由時報》。取自https://news.ltn.com.tw/amp/news/society/paper/11881

澳門特別行政區政府旅遊局。https://www.macaotourism.gov.mo/zh-hant/sightseeing/macao-world-heritage

田中泓 (2025年7月27日)。〈十年立法波折重重〉。《澳門日報》。取自https://www.macaodaily.com/html/2025-07/27/content_1847454.htm

錢朝陽與孫金灧(1999)。〈不是 “沙漠” 是 “绿洲”——漫谈澳门文化〉。《上海大學學報》: 社會科學版, 15-20

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space (D. N. Smith, Trans.). B. Blackwell. (Original work published 1974)

Retrieved from https://www.gov.mo/zh-hant/news/1067709/

Sheng, E. L., Zhang, A., &Yin, Y. (2023). A city profile of Macau—the rise and fall of a casino city. Cities, 140, 104431.

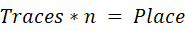

1. Introduction

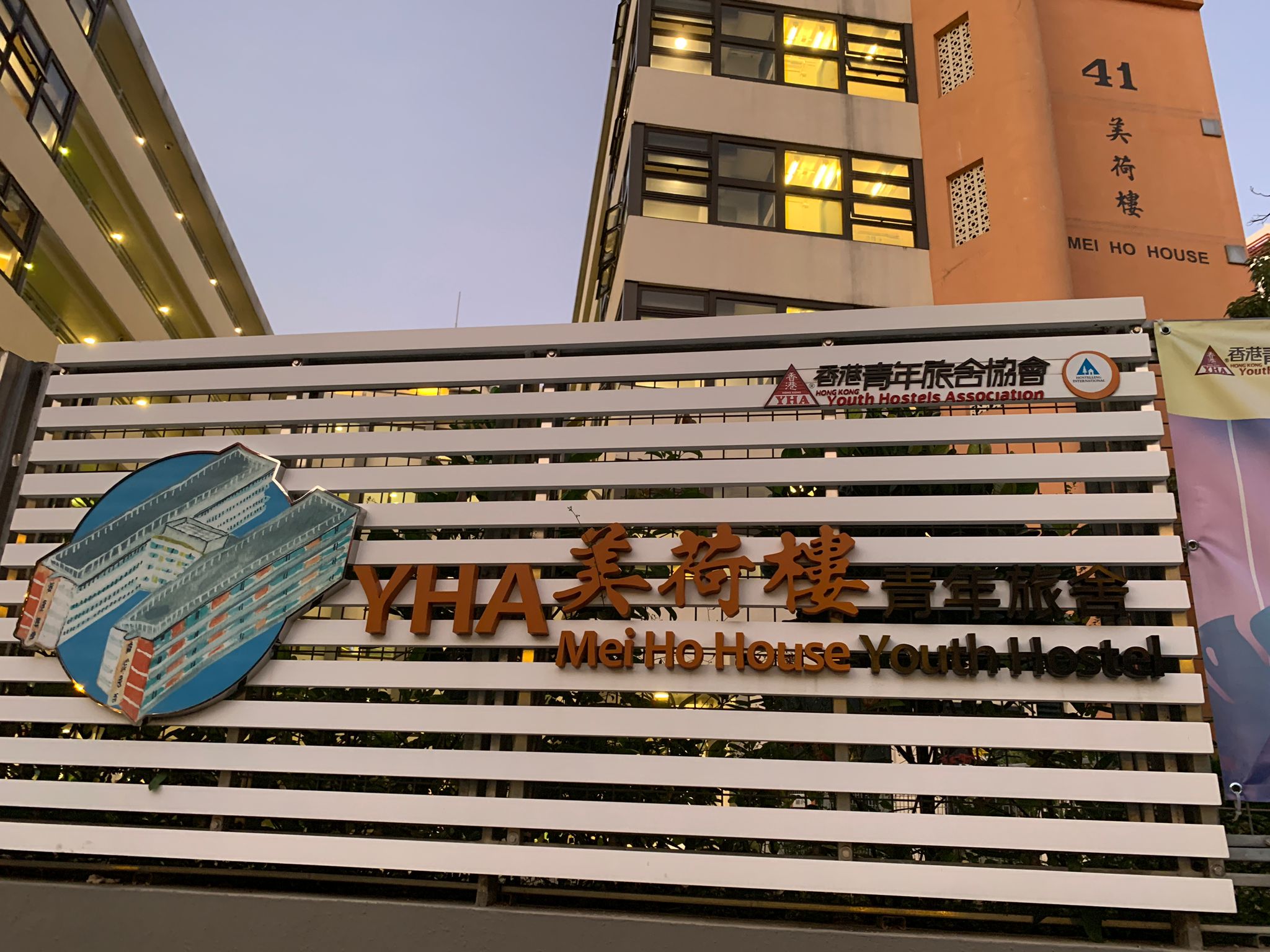

This project explores how Mei Ho House, the last remaining “Mark I” building was preserved and revitalized under “Partnership Scheme”. It would briefly introduce the reasons for the preservation and conversion of purpose after the revitalisation project. Some concepts from Cultural Geography would be discussed and applied to the case of Mei Ho House, trying to understand how the preservation would contribute to the preservation to the spirit of Hongkongers. We hope the case study would be the best way to comprehend the revitalisation project and thus promote the approach to another declared monument.

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

Drawing from Anderson’s framework (2021), a cultural geographical perspective investigates how places are dynamically ordered and given meaning through the ongoing composition of material and symbolic traces. The “material traces” are the tangible elements – the architecture of a building, or the functions of the place. Meanwhile, the “symbolic traces” are the intangible layers – the stories told about a place, the values it represents, the memories it holds. The coexistence between these two traces gives a place of meaning. It focuses on the interplay of power, memory, and identity in transforming a physical space into a meaningful place. This perspective examines how landscapes become culturally significant to a community where successive layers of cultural meaning are inscribed, erased, and reinterpreted through social practices and power relations.

Mei Ho House, originally constructed as an urgent response to the Shek Kip Mei fire in 1953, providing shelter for more than 50,000 refugees who once inhabited in the squatter, underwent revitalization and re-opened to public as YHA Mei Ho House Youth Hostel and Museum in 2013. This transformation actively constructs what Anderson (2021) described as “sense of place” by symbolically linking the building to cultural significance. As traces of resilience and community are reflected in times of adversity, Mei Ho House mirrors the Lion Rock Spirit (獅子山精神) and the Hong Kong identity. In Michel Foucault’s concept of power/knowledge, Mei Ho House represents “truth” as the “origin of Hong Kong public housing” and the symbol of “community spirit”. The conversion of the building into a museum and youth hostel is an act of governmentality and disciplinary technology, where the public is subtly disciplined to embrace the collective identity. This reflects Foucault’s idea of power as productive – it creates a place of public memories to foster social cohesion. In a nutshell, this project would apply the cultural geographical perspective by drawing several core concepts for its empirical analysis.

Picture 1 Demonstration of Mei Ho House flat in “Mei Ho House of Livelihood” (Time Out)

3. Empirical Analysis

Site Analysis

In 2004, Hong Kong Government has introduced a social public–private partnership named “Revitalising Historic Buildings Through Partnership Scheme”. NGOs were invited to submit proposals and become the service provider. The successful application required the service provider to engage resources on revival and maintenance work. Mei Ho House, the only remaining Mark I resettlement blocks, was the one listed on the first batch in the Scheme (Cheung & Chan, 2014).

Mei Ho House was one of the resettlement blocks after the Shek Kip Mei Fire. And the public estate building marks the origin of the Hong Kong public housing and was listed as Grade II historic buildings in Hong Kong in 2010 and proposed to revitalize the site into Youth Hostel (Antiquities and Monuments Office, 2010).

Under

the “Revitalising Historic Buildings

Through Partnership Scheme”, HKYHA tried to establish the significance and

preserve the site with new function, the association at last decide to keep the original use of it – to become a hostel,

which is like what it was.

Mei Ho House is now converted and renovated into 129 rooms for backpackers and solo travellers; the shared room would welcome everyone in the community (HKYHA, n.d.). Moreover, the Hostel remains its function from past to present: Communal place is offered for people to interact around the world. In the past, the bonding and the social connection in the community was strong. The Hostel aims to restore the tradition and the spirit of old Hong Kong.

Furthermore, part of Mei Ho House would be converted into a mini museum called “Mei Ho House of Livelihood”, aiming to promote the history and the neighborhood culture of the estate (HKYHA, 2020).

The idea of setting up the museum and preserving the building is highly related to the “The Sense of Place”, which is defined by Agnew and Duncan in 1989. The idea is that human, culture and environment are connected as network and how space becomes place (Agnew & Duncan, 2014, pp. 174–176). Mei Ho House symbolized the origin of public housing for refuges and squatter, and the sense of community: The residents pull together in times of trouble and support each other, which is the Lion Rock Spirit. The project preserved the collective memory, reminding the visitors how society and became “the witness of the housing development, a living archive of the community spirit and the history behind it, which Anderson (2021) has mentioned as a trace to ‘express collective will and collective thought’.

Picture 2 Mei Ho House before and after. (HKYHA)

Different Stakeholder Involved

There were different stakeholders

involved in Mei Ho House renewal, under revitalising historic buildings through

partnership scheme besides the government who mainly provided the financial

support, promoted public participation in the protection of historical

buildings, and guidelines for the project (Development Bureau, 2025), the

community and NGOs were also critical for the project.

First, the NGOs- Hong Kong Youth

Hostels Association (HKYHA) was being chosen by the Advisory Committee on

Revitalization of Historic Buildings (ACRHB) for providing service for the Mei Ho

House in 2009 (Lam et al., 2022). It also responsible for future maintenance,

engaged consultants ‘(including architects, structural engineers, building

services engineers, quantity surveyors and heritage conservation consultants)

to undertake tender assessment, contract administration and site supervision of

the project’ (Legislative Council, 2010).

Next, for the community, generally

members in Sham Shui Po District Council, Legislative Council and Antiquities

Advisory Boardon supported the projects (Legislative Council, 2010). Hong Kong

Housing Authority (n.d.) have mentioned that sustainable housing development

cannot be achieved without the participation and support of residents in our

estates and district councils. To solicit public opinion and explore how to

revitalize the building and better serve the community, the Hong Kong

Development Bureau held a competition for various professional organizations

(Hong Kong Housing Authority, n.d.).

Moreover, Chinney Construction Co. Ltd. was commissioned to transform the Mei Ho House. They preserved as many original historical elements as possible, such as metal grilles, metal doors, and kitchen countertops. Their effort for trying the best to preserve the historical value in Mei Ho House was recognized by the Chartered Institute of Building (Chinney Construction Co. Ltd., 2025).

4. ConclusionTo conclude, the “Partnership Scheme” would be the best way to preserve the building itself and the value behind it. From a cultural geographical perspective, Mei Ho House powerfully illustrates the interplay of material and symbolic traces. The preservation stands as tangible witnesses to the community, reaffirming the Lion Rock Spirit. Through subtle mechanisms of memory-making, the site reinforces a collective narrative of community and endurance. The project would be the way to explain the idea of sense of place. The renovated public estate building is the epitome of old Hong Kong, showing how they were striving in the society. Its success strongly advocates extending the “Partnership Scheme” to other monuments, ensuring that Hong Kong’s shared stories continue to resonate with present and future generations.

References

Agnew, J., & Duncan, J. (Eds.). (2014). The Power of Place (RLE Social & Cultural Geography) (pp. 174–176). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315848617

Anderson, J. (2021). Understanding cultural geography: Places and traces (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367814816

Antiquities and Monuments Office. (2010). Revitalisating Historic Buildings Through Partnership Scheme Batch I Project Conservation Management Plan prepared for Heritage Impact Assessment for Adaptive Re-use of Mei Ho House as Youth Hostel Conservation Management Plan Content. https://www.amo.gov.hk/filemanager/amo/common/form/MHH-HIA.pdf

Cheung, E., & Chan, A. P. C. (2014). Revitalizing Historic Buildings through a Partnership Scheme: Innovative Form of Social Public–Private Partnership. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 140(1), 04013005. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)UP.1943-5444.0000161

Chinney Construction Co. Ltd. (2025). PROJECTS-REVITALISATION OF ME HO HOUSE-SHEK KIP MEI. https://www.chinneyconstruction.com.hk/mei-ho-house/

Development Bureua. (2025). The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.https://www.devb.gov.hk/filemanager/tc/content_85/Annex_3.pdf

HKYHA. (n.d.). Background Information - Mei Ho House Revitalisation Project. YHA – Hong Kong Youth Hostels Association. https://www.yha.org.hk/en/our-services/mei-ho-house-revitalisation-project/significance-and-design/

HKYHA. (2020). Heritage of Mei Ho House - YHA – Hong Kong Youth Hostels Association. YHA – Hong Kong Youth Hostels Association. https://www.yha.org.hk/en/our-services/mei-ho-house-revitalisation-project/heritage-mei-ho-house/

Hong Kong Housing Authority. (n.d.). STAKERHOLDER ENGAGEMENT. https://www.housingauthority.gov.hk/hdw/en/aboutus/publications/ehs0708/stakeholder01.html

Lam, E. W. M., Zhang, F., & Ho, J. K. C. (2022). Effectiveness and Advancements of Heritage Revitalizations on Community Planning: Case Studies in Hong Kong. Buildings, 12(8), 1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12081065

Legislative Council. (2010). 7QW–Revitalisation Scheme–Revitalisation of Mei Ho House as City Hostel. https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr0910/english/fc/pwsc/papers/p10-10e.pdf

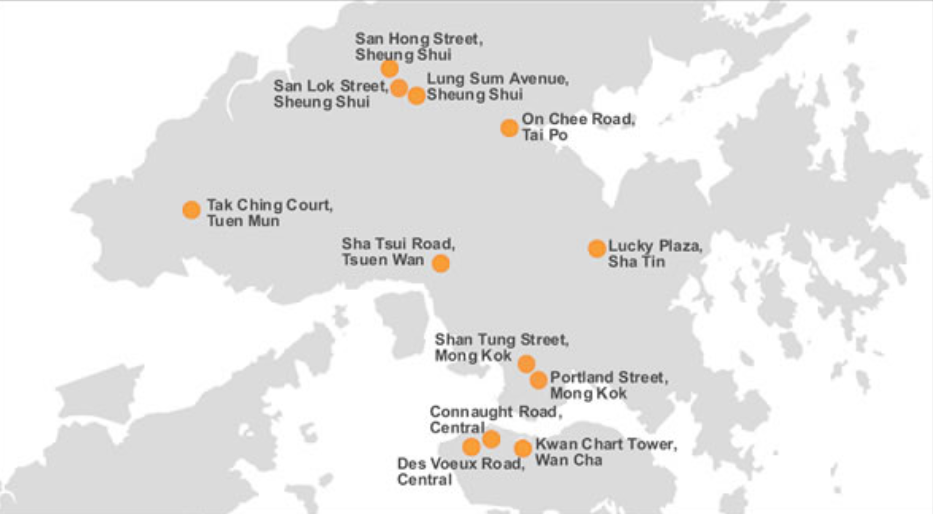

1. Introduction

Tai O is located on the northwest coast of Lantau Island, at the mouth of the Pearl River. A natural bay provides a protective barrier for the local ecosystem. The intertidal wetlands and abundant marine resources have nurtured unique stilt houses, water village imagery, and the cultural brand of "the Venice of the East" (Tai O Fishing Village, n.d.).

Figure

1: Map of Tai O (Sources: Google map)

Best known as one of the existing fishing villages in Hong Kong, Tai O’s history can be traced back to 800 years ago. It was the home of the Tanka people, one of the earliest groups to emigrate to Hong Kong. The population was around 10,000 in the early 20th century. Yet, the number has been dropping since then (Mak, 2011).

Figure 2: 1930s Tai O (Source: Gwulo)

Figure 3: 1981 Drying shrimps (Source: Andrew Suddaby)

The

residents earned for a living by mostly fishing and salt farming, others worked

in the fields of agriculture and trading (Kwan & Tam, 2021).

Figure 4: 1981 Stilt warehouses (Source: Andrew Suddaby)

Figure 5: 1978 Fishing craft at anchor (Source: gordonvr)

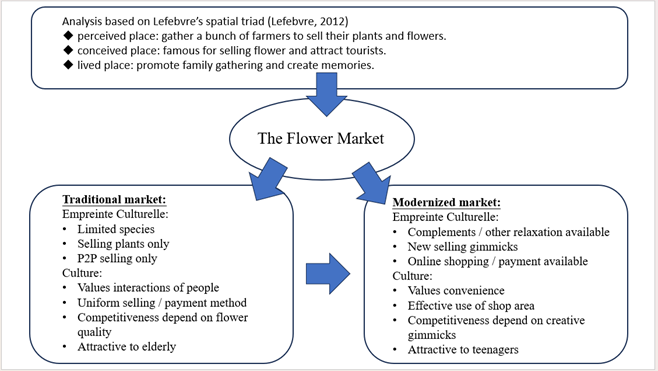

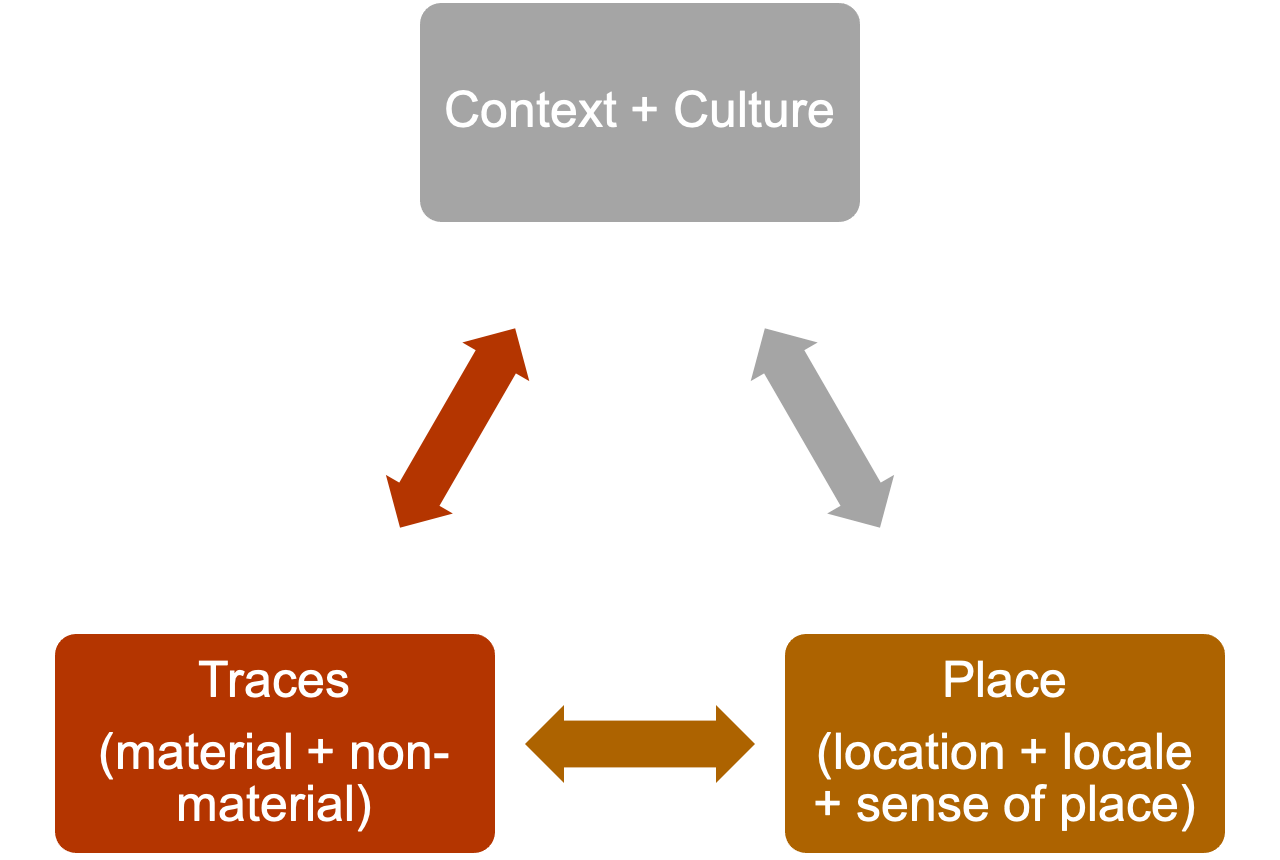

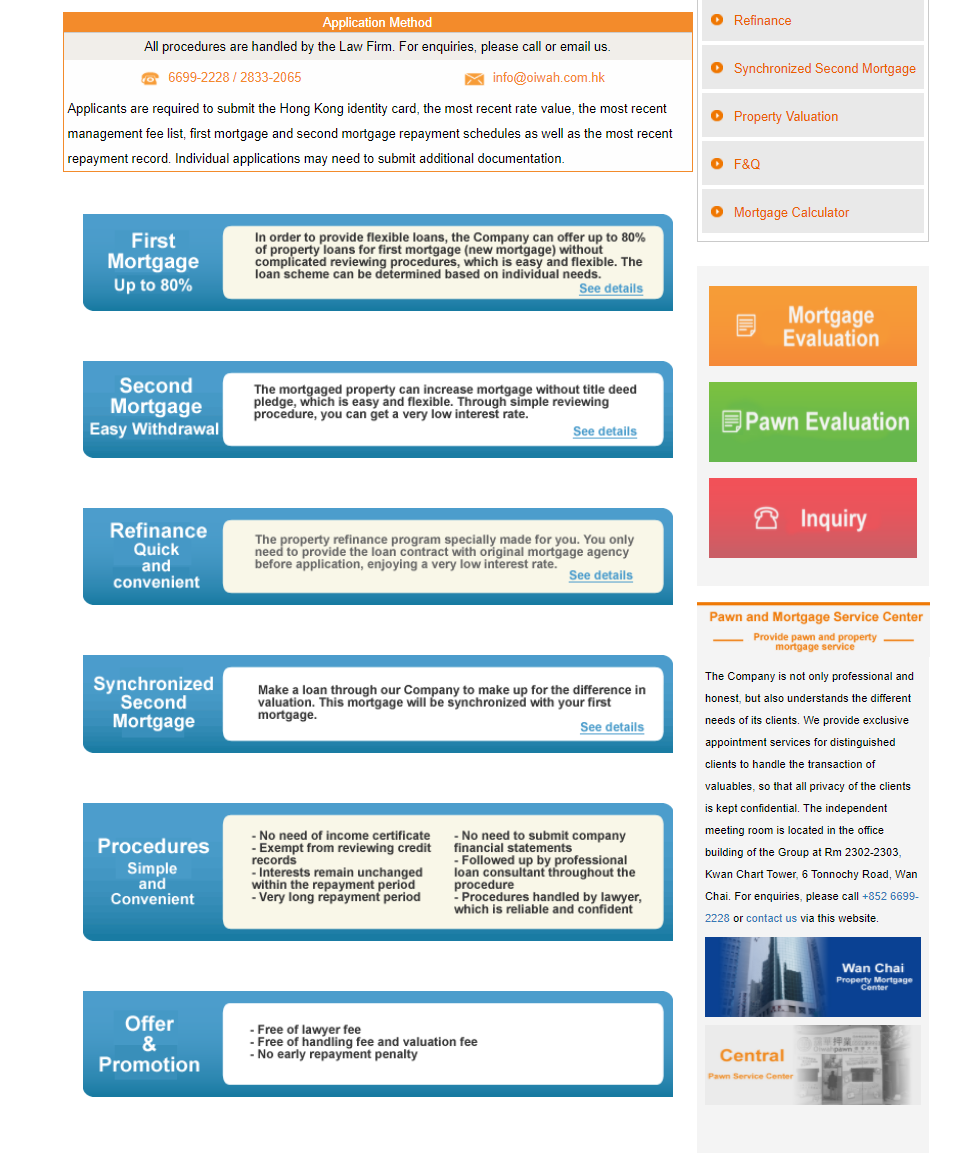

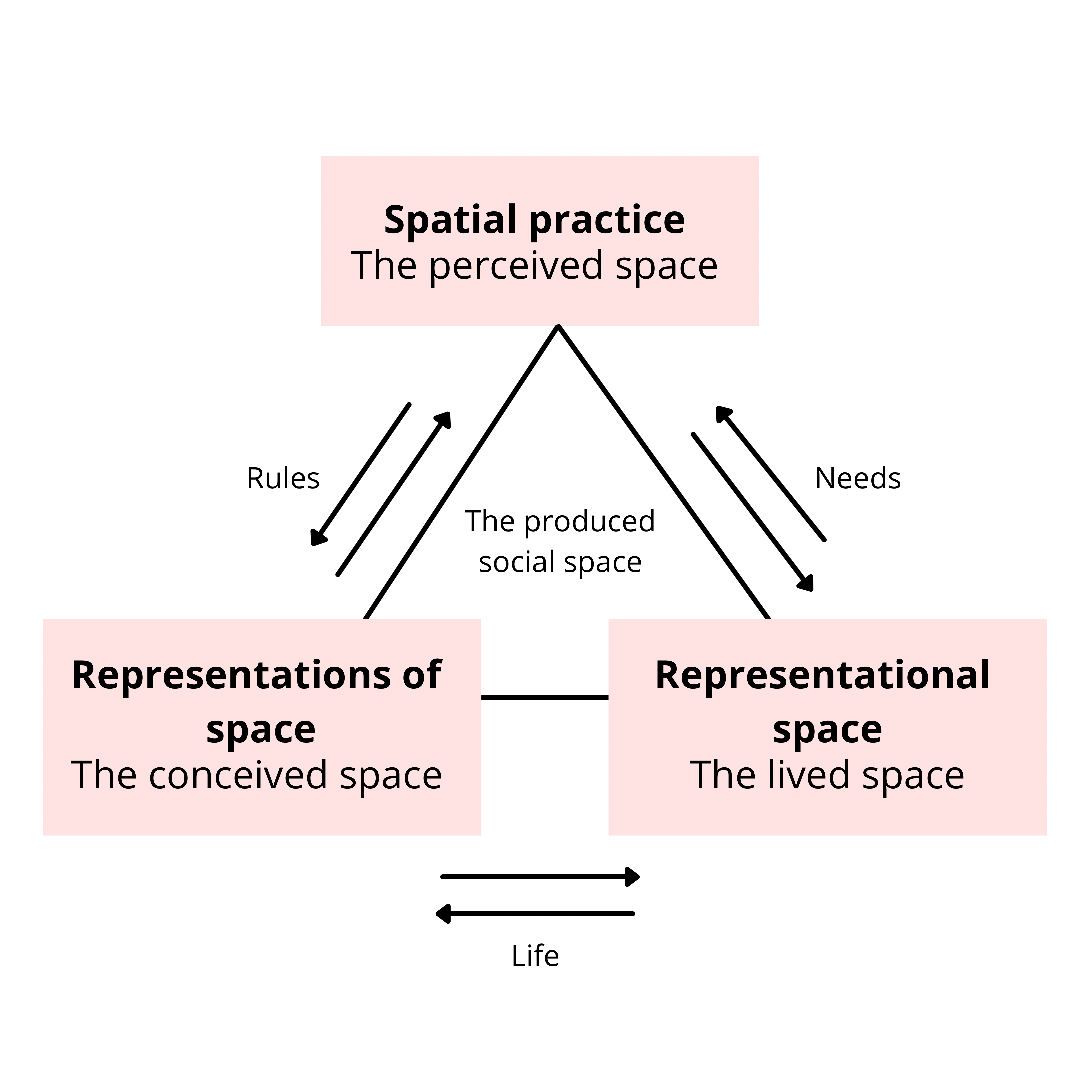

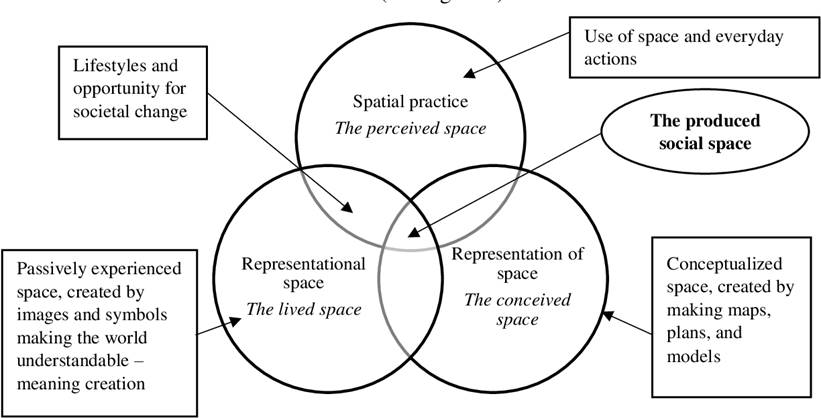

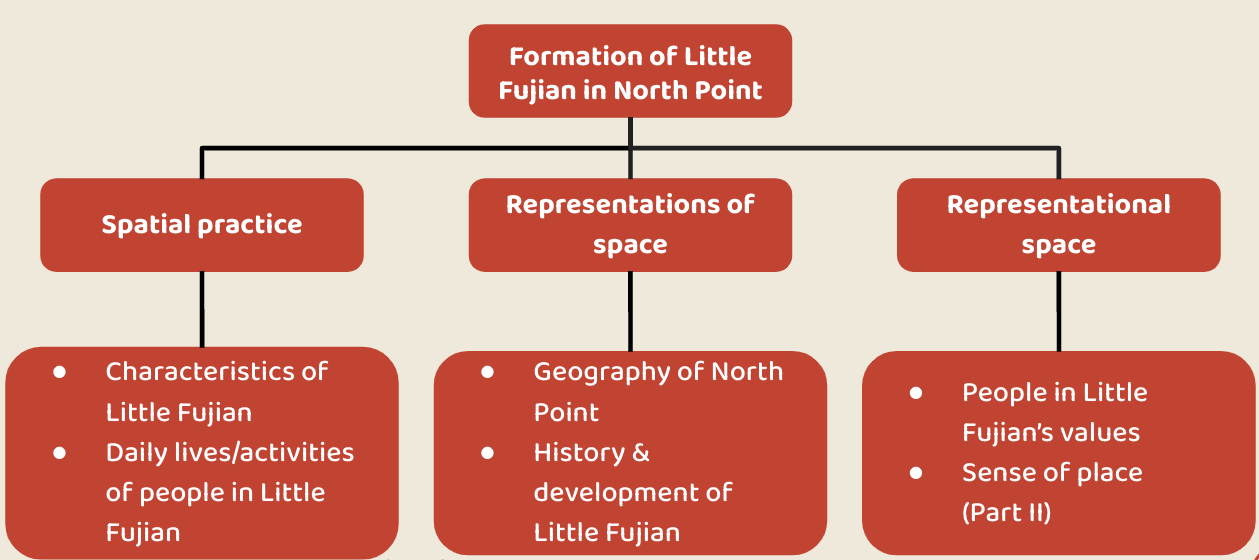

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

Research Question

How does tourism development and power affect the

spatial triad and shape Tai O’s cultural landscape from a fishing village to a

tourist hotspot?

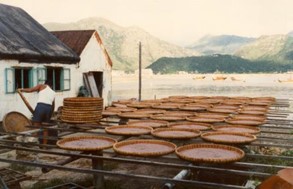

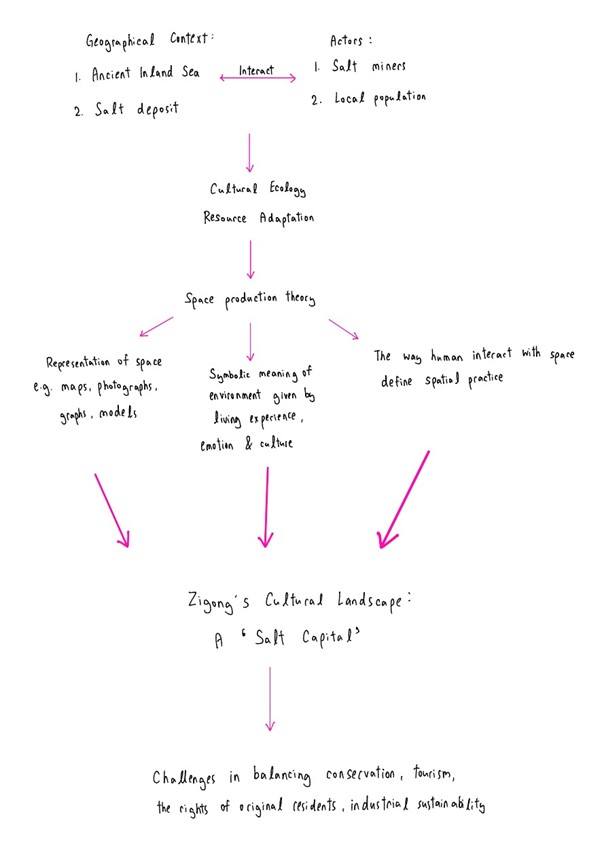

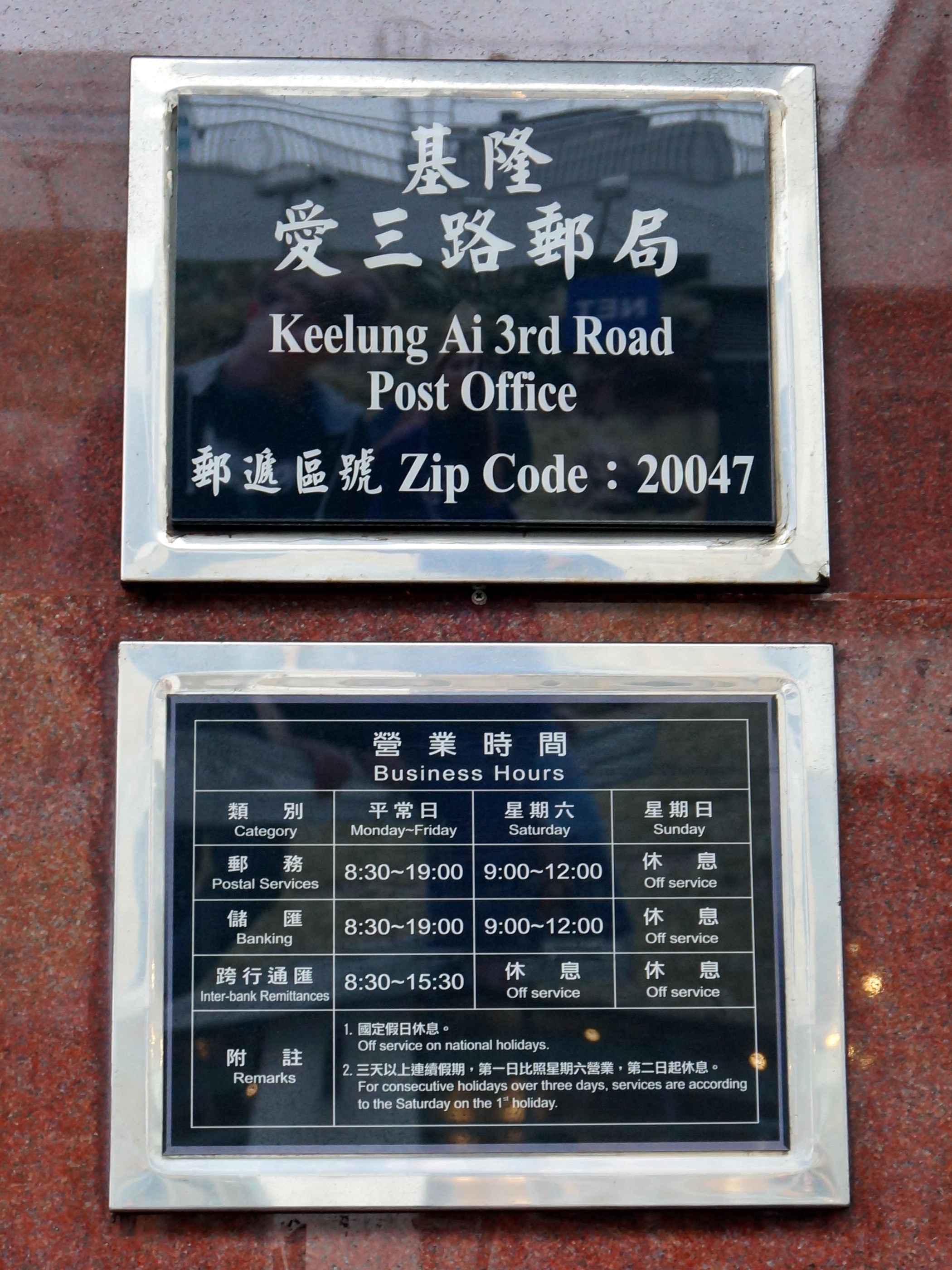

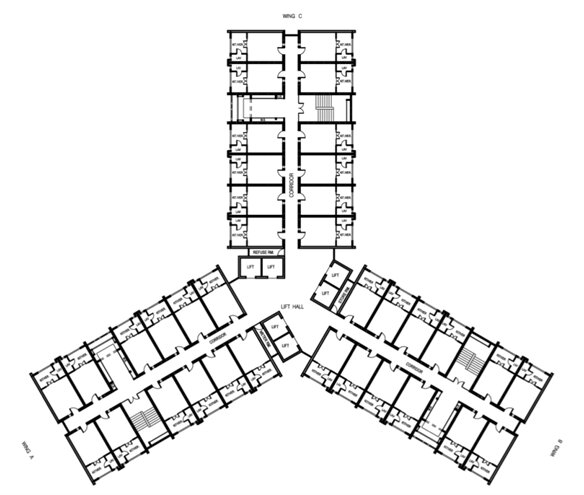

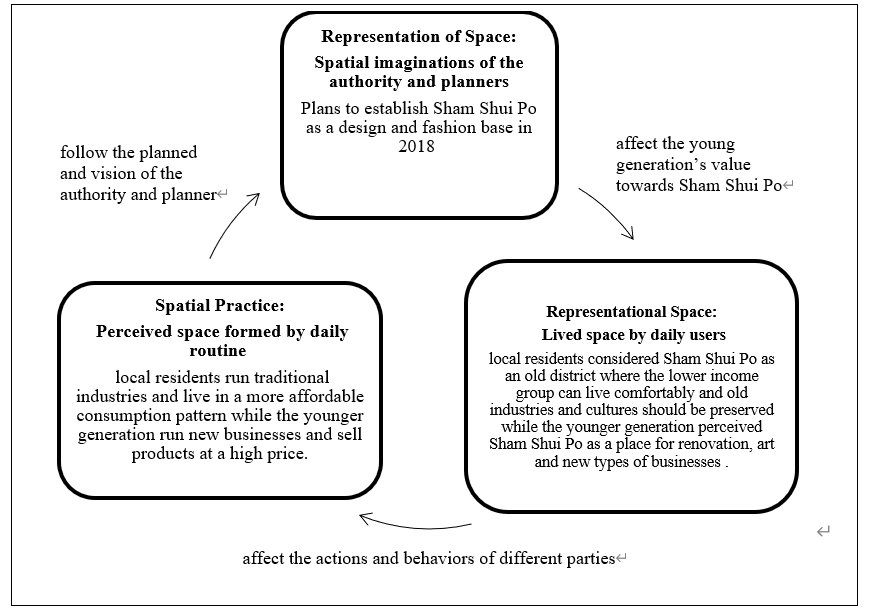

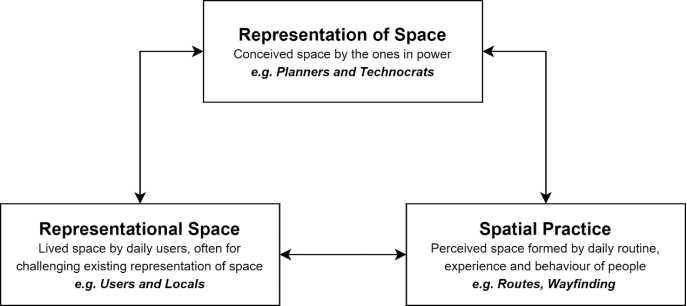

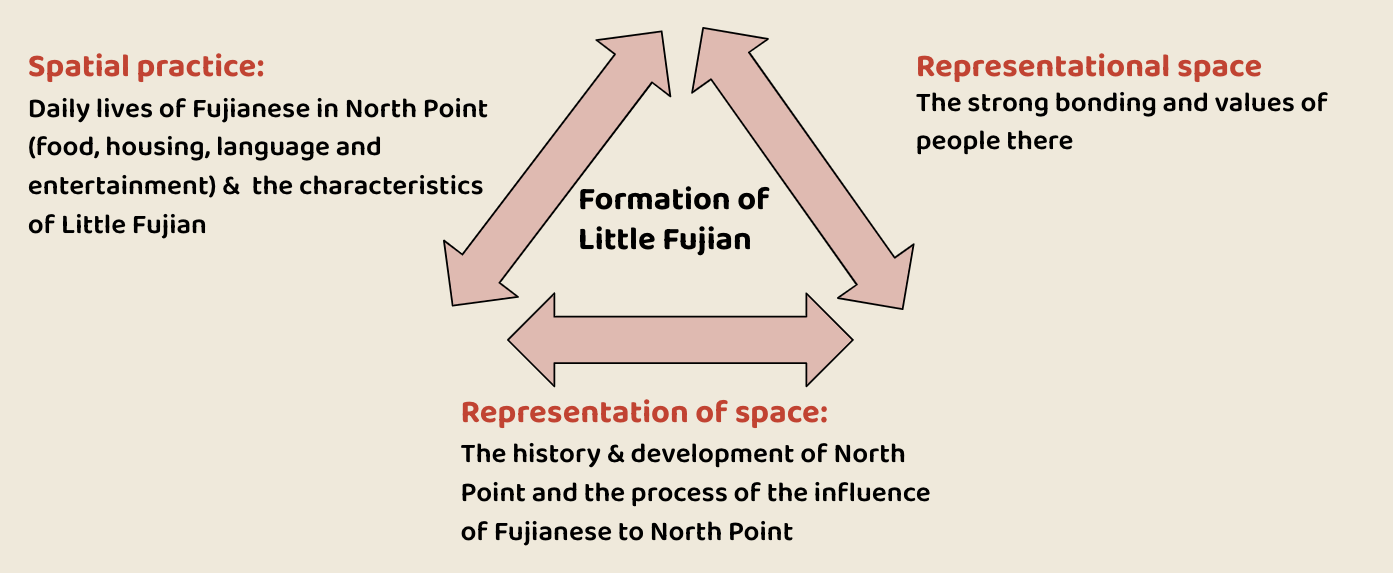

Figure 6: Conceptual framework

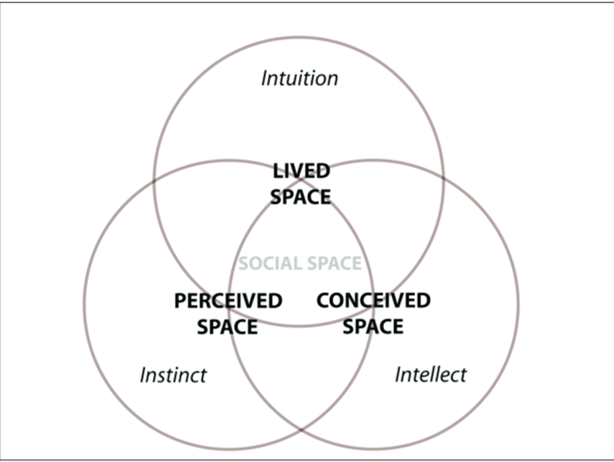

In this

study, Henri Lefebvre’s spatial triad is employed to analyze how tourism

development transforms Tai O’s cultural landscape from a functional fishing

village to a commodified tourist site. The triad includes: conceived space

which covers top-down planning and tourism strategies, perceived space that

includes tourists’ perceptions and media image, and lived space which focuses

on local interactions and cultural expressions(Lefebvre, 1991). The arrows show

how these 3 aspects affect each other .

In Foucault‘s power, everyone has the capacity to act, the power is not repressive, instead it is productive. Power is the relationship between people when they act on the actions of others (Lynch, 2011). The power structure is absent in society. But for the Political economy theory, power is a tool for ruling the state, and also a means of violence and coercion by the ruling class to carry out exploitation and oppression. In this project, we are combining both theories:

Within the power structure, individuals also seek to consolidate their own power simultaneously.

This is to explain the power struggle between the government and tourism agencies on the one hand and Tai O residents on the other hand in the process of turning Tai O from a fishing village to a tourist spot.

Another approach is the Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad. We are using the concepts of spaces to show how they influence one another, and most importantly, they explain why Tai O is not merely a fishing village or a tourist spot, but a socially produced space (Lefebvre, 1991).

3. Empirical Analysis

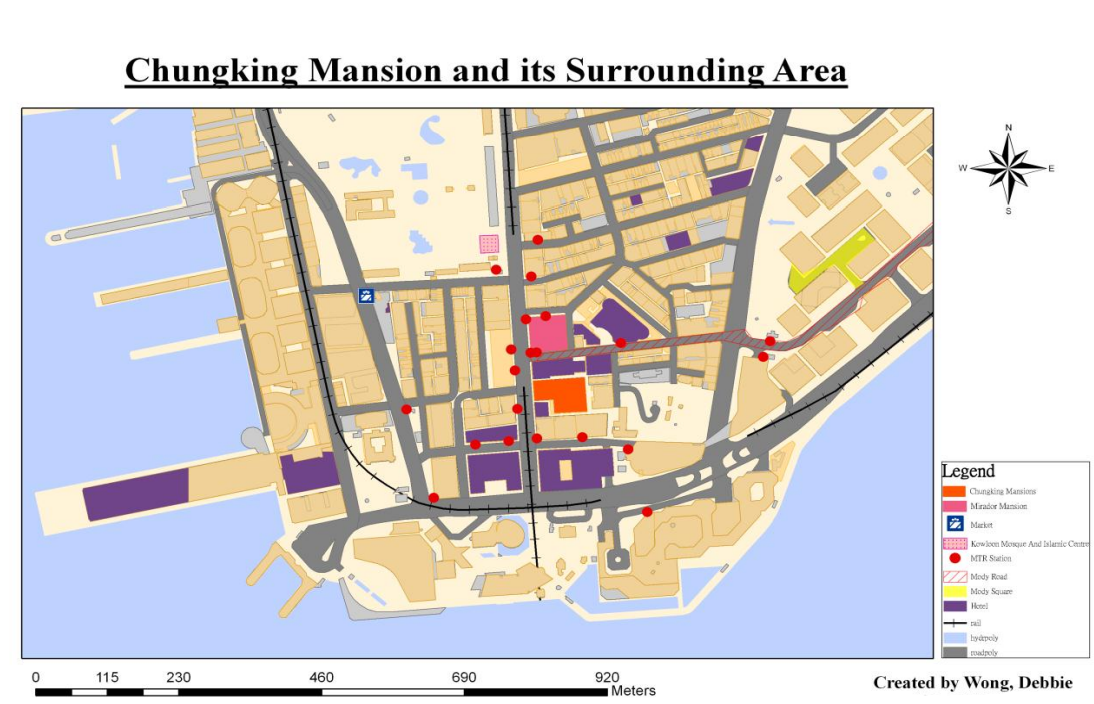

Conceived Space: How did the government turn Tai O to a tourist spot?

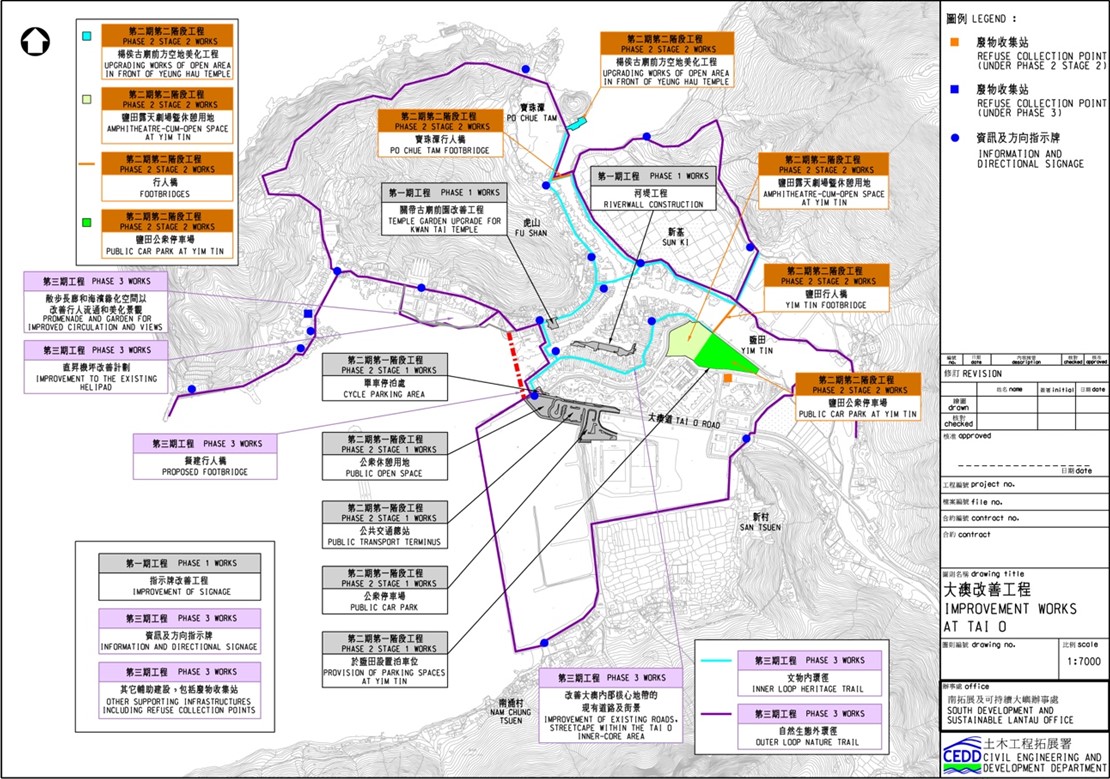

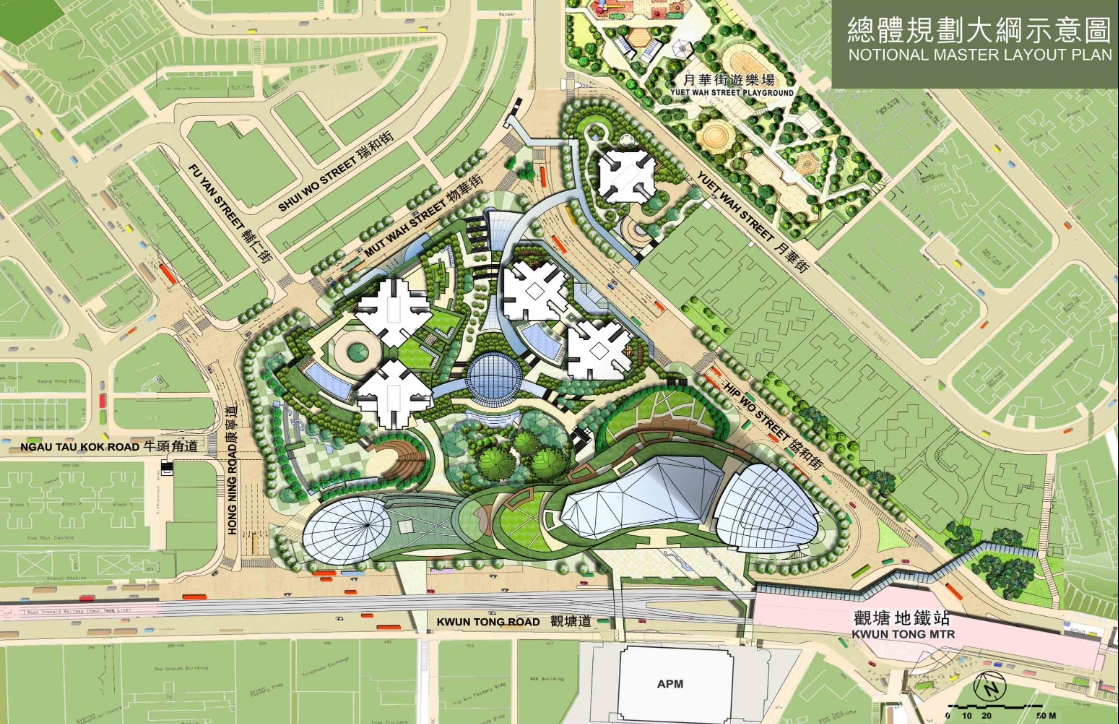

Turning Tai O from a fishing village to a tourist spot, the government implemented some projects, with the primary aim of alleviating traffic congestion and enhancing tourism capacity. These plannings of the use of Tai O’s space are categorized as the conceived space in the spatial triad, in which power is primarily exercised through top-level government planning and brand narratives of “Venice of the East” by tourism agencies. One consideration is that this power dynamic manifests where the government and large tourism stakeholders dominate resource allocation and spatial transformation, while local residents passively accept policy outcomes (South Development and Sustainable Lantau Office - Improvement Works at Tai O, n.d.).

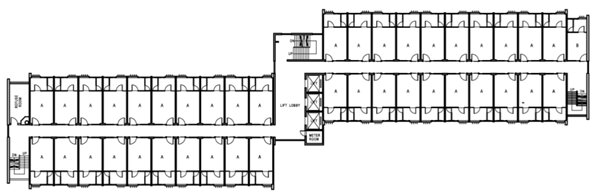

Figure 7 : Improvement Works at Tai O – Project Scope (Source: Civil engineering and Development Department)

To begin with, it is vital to understand the role of the government throughout the transformation of Tai O. Research indicated that the government exercised absolute power over the definition and allocation of spatial resources by designating conservation areas and implementing the “Tai O Improvements Project” in phases, including bridge construction, transportation improvements (South Development and Sustainable Lantus Office, n.d.). While this aims to protect cultural and natural heritage, it also fundamentally restricts residents’ autonomy in land use and reinforces the dominant position of national administrative agencies in the allocation of spatial resources (Du Cros & Lee, 2007).

Figure 8: Artist Impression – Proposed Footbridge at Yim Tin

(Source: Civil engineering and Development Department)

Secondly, how does this dominant power shape the conceived space of “Venice of the East” (Leung et al, 2021)? From our observation, the more productive power is reflected in the branding of “Venice of the East”. The government and tourism-organizations have redefined Tai O from a functional fishing village into a tourist attraction, offering exotic experiences for consumption. This government wields decision-making authority (top-down), which produces a new spatial reality and tourist expectations, laying the foundation for subsequent commercialization and the spatial practices in living space. For example, they have proposed the phased implementation of the “Tai O Improvement Works”, including elements like bridge construction, traffic enhancements, and additional parking facilities, to meet the demands of increased visitor traffic.

This conceived space from the top level profoundly reshapes the daily practices (lived space) and perceptions of residents and tourists (perceived space) in Tai O, thus entering our next analytical dimension—lived space.

Lived Space: What tensions arise for Tai O residents as tourism transforms both livelihoods and cultural heritage?

In Lefebvre’s spatial triad, lived space constitutes the experiential and symbolic dimension where inhabitants imbue the environment with personal and collective meanings, often resisting dominant conceptions through imaginative overlays and embodied practices (Lefebvre, 1991). In Tai O, this manifests as a palimpsest of traces—layered inscriptions of Tanka heritage and adaptive identities—that emerge dialectically amid the village’s transformation from a fishing enclave to a tourist site. For instance, residents imbue spaces like stilt houses with nostalgic traces of nomadic livelihoods, linking daily rhythms to ancestral adaptability (Kwan & Tam, 2021). Temples of Guan Yu and Tin Hau, traditional festivals like dragon boat races are not only tourist attractions but also spiritual value to the residents which carries community unity and maritime worldview, maintaining oral history and traditional rituals (Ma, 2015).

Figure 9: Tai O San Tsuen Tin Hau Temple (Source: Home Affairs Department)

However, when these elements are incorporated into tourism promotion by the government to maintain attractiveness, it objectively contributes to the preservation of cultural heritage, but its intrinsic meaning faces the risk of being hollowed out. For example, privately owned stilt houses are converted into guesthouses, residents’ privacy and daily rhythms (lived space) are forced to give way to the gaze and experience of tourists (perceived space of tourists). Another example is the symbolic meaning of the Sun Ki Bridge, a profound imprint of community agency, which is also facing challenges with tourism. This bridge was built with funds raised by residents using traditional “Kun Dian” wooden pillars, which carries the collective memory of solidarity and symbolizes resistance against bureaucratic neglect (Wan & Chan, 2017). However, its primary function has now shifted to serving tourists, diluting its former symbolic meaning as a source of community pride. This transformation has introduced noise and pollution to Tai O, and created a complex emotional dissonance among residents. The autonomy of residents and their living space are being eroded by tourist spaces which led to residents’ emotional dissonance and discomfort.

Although some residents express opposing reactions, there is pragmatic acceptance of changes like stilt house repurposing for homestays, which disrupts privacy but sustains livelihoods, highlighting affective dissonances in lived space (Wan & Chan, 2013). Therefore, we would like to say that Tai O’s “lived space” is like a rewritten book, covered with the new strokes of tourism commercialization, while stubbornly preserving and constantly reproducing the ancient inscriptions of ethnic identity and community memory, forming a dynamic and tense field of resistance.

Perceived Space: How do locals and tourists differently construct meaning and attachment to Tai O’s space?

The blueprint for “conceived space” inevitably reshapes the “perceived space” of residents and tourists - their daily activities and economic practices (Lefebvre, 1991).

In responding to tourism demands, residents’ traditional livelihood strategies have undergone profound transformations: backyard shrimp paste marketing has become street performances, and fishing skills have been packaged as paid experiences (Elkin et al., 2021). This confirms the productive nature of power, it produces new behavioral patterns and economic relations by connecting modern identities to traditional fishing economies (Ma, 2015).

Figure 10: Residents teaching how to make fishing net (Source: Tai O Travel eFun)

Also, tourism yields economic revitalization, such as income from boat tours and dried seafood markets. It poses environmental threats like waterway pollution from increased boat traffic and waste, eroding ecological traces tied to traditional practices. However, this is not a one-way domination. Under the challenges, the residents demonstrate the agency emphasized by Foucault, actively transforming their life skills and cultural knowledge into economic capital. This provides a chance to fight for their livelihood and voice within this power structure, demonstrating the dialectical nature of power dynamics and the idea that individuals have their own power rather than remaining passive (Lynch, 2011).

For the tourists, before the intervention of power, tourists’ perception of Tai O remained superficial-static images of stilt houses and fishing boats captured on cameras due to the relatively closed cultural environment of Tai O. After the power dynamic reshapes the sensory experience in Lefebvre’s spatial triad, tourists shift from purely visual consumption to multi-sensory engagement (Ma, 2015). For instance, the tactile act of making shrimp patties over charcoal evokes the sense of smell while the kinesthetic learning of weaving fishing nets enables visitors to physically enter the fishing village waterways which were previously accessible only from afar, and to experience Tai O from the perspective of the locals while on a swaying boat.

All these new commercial

interactions create entirely new ways of perceiving place. This transforms

still photography into dynamic, immersive experiences, enhancing their

imagination and understanding of “life on the water”. This process raises

emotional resonance, cultural identity, and even an attachment to memories.

Through the analysis of the Lefebvre’s triad, this study shows that conceived space drives branding and infrastructure; perceived space adapts routines for economic survival; lived space resists via symbolic heritage. This interplay writes the complex narrative of Tai O’s transformation from a fishing village to a tourist attraction, yields benefits like preservation but tensions in identity and sustainability. Future policies should enhance community participation for equitable transformation.

References

Du Cros, H., & Lee, Y. S. F.

(2007). Heritage tourism and community participation: A case study of Tai O,

Hong Kong. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 2(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.2167/jht031.0

Elkin, D. K., Leung, C. Y., Wang, X., & Wernli, M.

(2021, May 7). Data Commoning in Tai O Village: History, the urban

periphery, and technology in spatial agency practice. PolyU Scholars Hub. https://research.polyu.edu.hk/en/publications/data-commoning-in-tai-o-village-history-the-urban-periphery-and-t/

Google. (n.d.). Google Map of Tai O.(2025, November 23) https://maps.app.goo.gl/7xtotzSZXgC4u7kZ9?g_st=ipc

Gwulo. (n.d.). 1930s Tai O [Photograph]. https://gwulo.com/media/19451

Gwulo. (n.d.). Drying shrimps [Photograph]. https://gwulo.com/media/22566

Gwulo. (n.d.). Fishing craft at anchor, Tai O, 1978 [Photograph]. https://gwulo.com/media/30261

Gwulo. (n.d.).Stilt warehouses [Photograph]. https://gwulo.com/media/22560

Hong Kong fun in 18 districts - Tai O San Tsuen Tin Hau Temple. (n.d.). [Photograph]. https://www.gohk.gov.hk/en/spots/spot_detail.php?spot=Tai+O+San+Tsuen+Tin+Hau+Temple

Kwan, C., & Tam, H. C. (2021). Ageing in place in disaster prone rural coastal communities: a case study of Tai O Village in Hong Kong. Sustainability, 13(9), 4618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094618

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.). Blackwell Publishing. (Original work published 1974)

Leung, C., Elkin, D. K., Norah, W.

X., & Suntikul, W. (2021, August 20). Inequality in Development Futures:

Tourism Economies Construction Technology in Tai O, a Village near Hong Kong.

Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture. https://www.acsa-arch.org/chapter/inequality-in-development-futures-tourism-economies-construction-technology-in-tai-o-a-village-near-hongkong/

Lynch, R. A. (2011). Foucault's theory of power. In D. Taylor (Ed.), Michel Foucault: Key concepts (pp. 13-26). Acumen Publishing. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/michel-foucault/foucaults-theory-of-power/FDBA0D73DFE14C6AEE665C14FB26DAA2

Ma, E. (2015). The 'unbearable' beauty of a cultural village: Performing and negotiating heritage in Hong Kong's Tai O. Tourist Studies, 15(1), 58–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797614561025

Mak, K. (2011). Community participation in tourism : a case study from Tai O, Hong Kong. https://doi.org/10.5353/th_b4642931

South Development and Sustainable Lantau Office - Improvement works at Tai O. (n.d.).https://sslo.cedd.gov.hk/en/our-projects/local-improvement-works/tai-o/index.html

Tai-o.com.hk. (n.d.). Fishing

culture and activities in Tai O [Photographs]. https://www.tai-o.com.hk/fishing-culture

Tai O Fishing Village. (n.d.). Lantau Island. https://www.lantau-island.com/tai-o-fishing-village

Wan, Y. K. P., & Chan, S. H. J. (2013). Social capital and community participation in tourism planning in Tai O, Hong Kong. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(6), 836-854. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.750369

1. Introduction

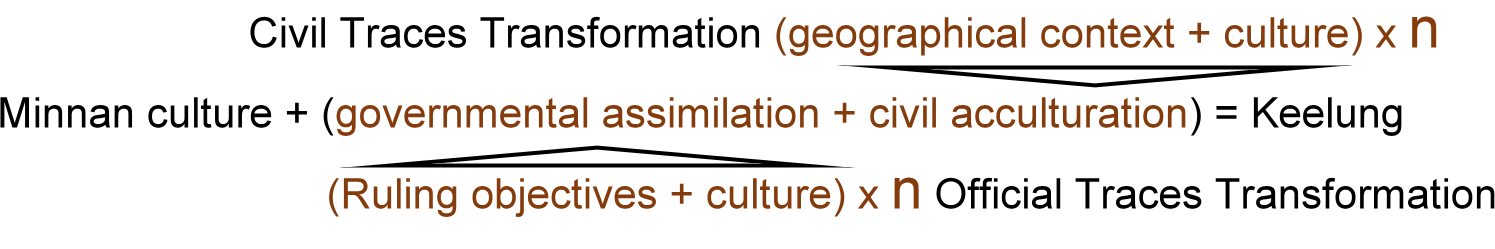

Taipei’s Wen-Luo-Ting, is an area surrounded by Wenzhou street, Roosevelt Road, Tingzhou Road and Xinsheng South Road, and it is a community with numerous bookstores, literary events, and historical underground architecture. With the characteristics of second-hand book stalls in Guling Street in the 1960s and after relocations over time, it consisted of the political idea of anti-intellectualism and identity in Taiwan, making it a compelling case for cultural geographical analysis.

To start with the cultural characteristics of Wen-Luo-Ting, the community is formed by traces including ideological literature, underground spaces with historical political background, and cultural activities successively resisting against dominant power. With the intersection of the university-surrounded location, changing importance of second-hand books, and historical state repression under Japanese colonial rule, Martial Law, White Terror, the community continuously affected by the cultural values of freedom and marginal knowledge.

Based on cultural geography and Foucault’s theory of power, this paper will analyse how dominating and resisting political and social powers continually create, erase, or change traces, and so reshaping the community’s meaning from covert revelation centre to modern cultural innovation site.

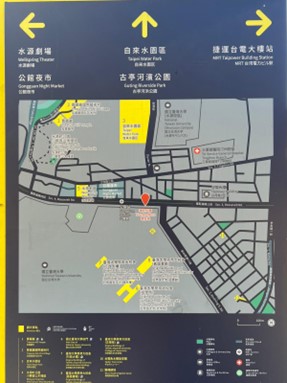

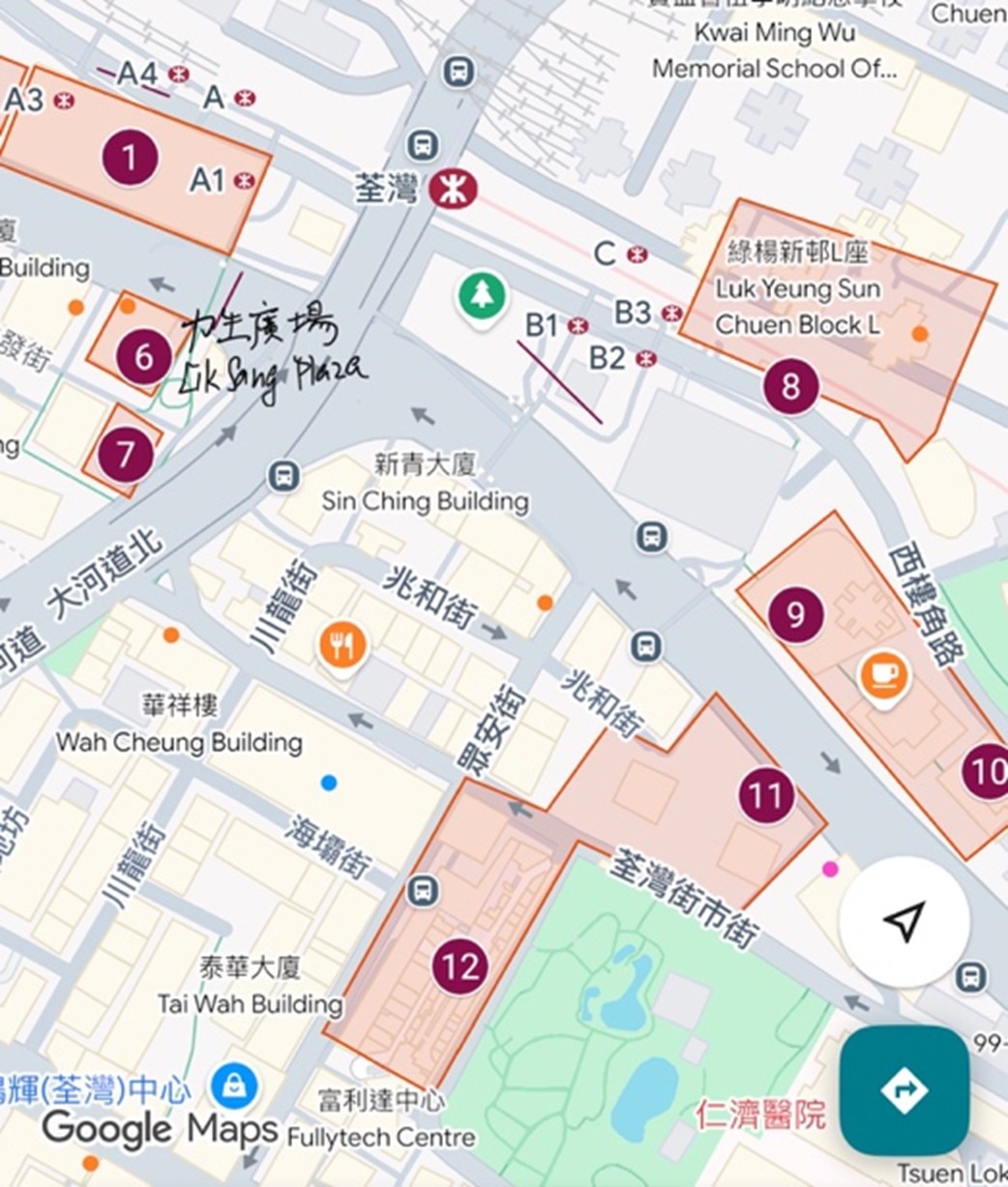

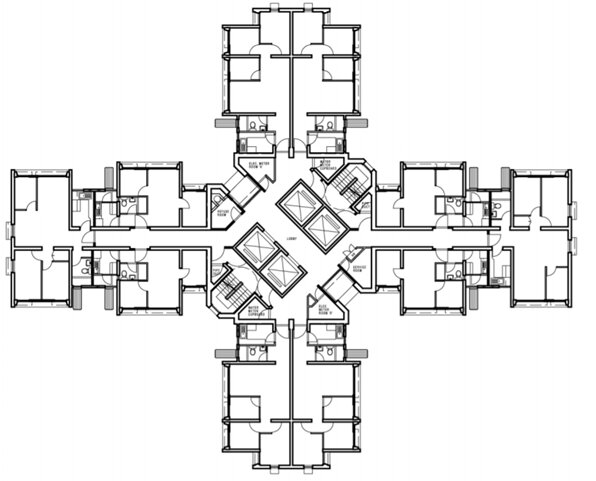

Map photo taken by groupmate at Wen-Luo-Ting

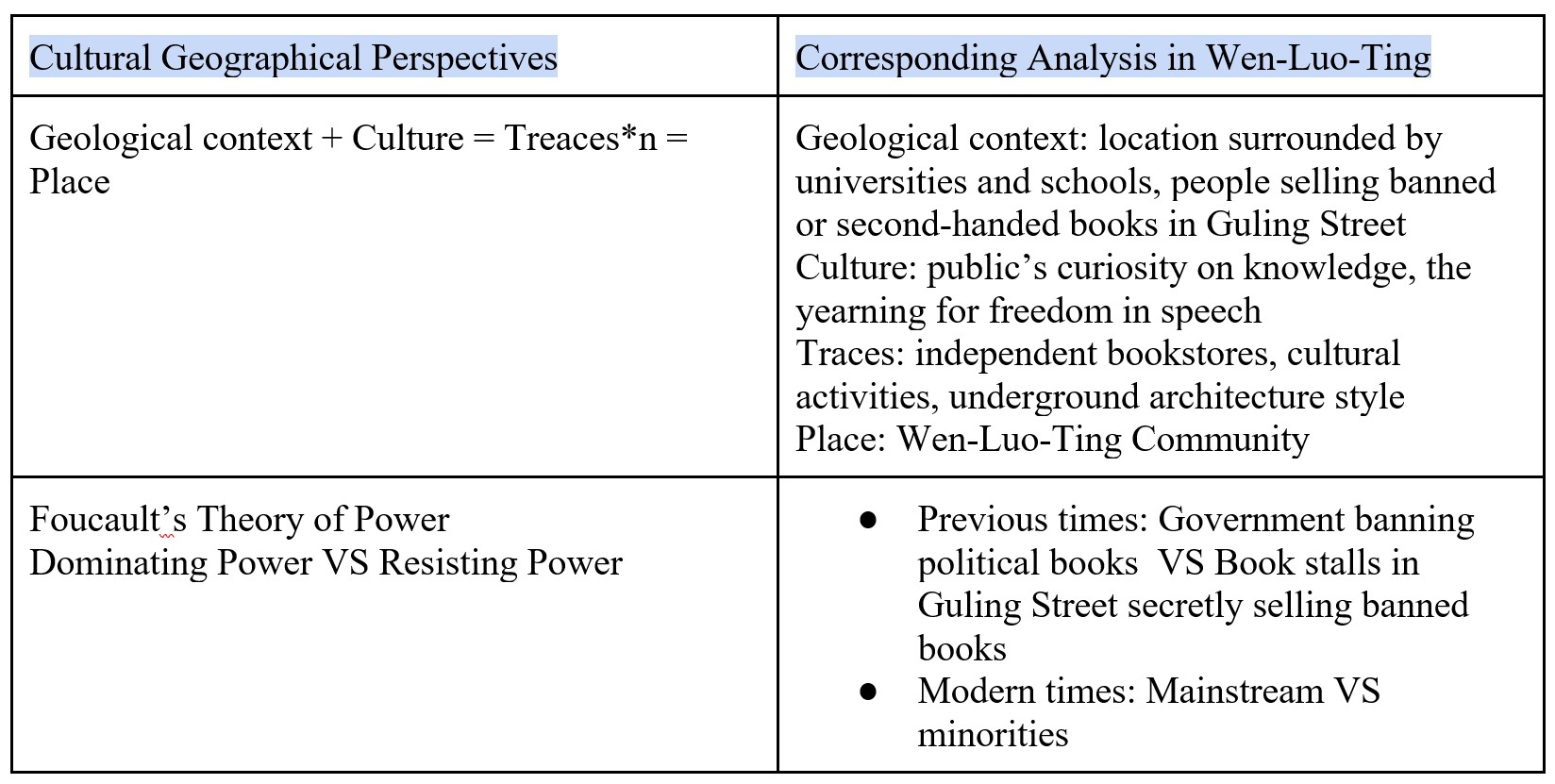

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

Investigation on a place in a cultural geographical perspective is not only describing the view, but also seeking the path of development behind all the appearing elements. A place is constituted by an imbroglio of traces, which are marks, residues or remnants made by the intersections of culture and context (Anderson J., 2010).

Wen-Luo-Ting is geographically located in the centre of the school-town atmosphere, acting as a diverse cultural community flourishing by different independent bookstores and literature-related activities. Its precursor as an area concentrated with second-handed book stalls in Guling Street paved the road for its transformation to the Wen-Luo-Ting community. Apart from traces including independent bookstores in different themes and various cultural activities, underground architecture style representing the freedom of speech also shape the unique place and attract many visitors.

While existing traces keep changing under the influence of power proposed by Foucault (Christensen, 2024), the place is regarded as a dynamic entity. During the confrontation between dominating power and resisting power, traces are either disappeared or created to modify the significance and role played by the place, thus forming a complex culturally-distinctive enclave.

In the study, we can see the role of the Wen-Luo-Ting community evolving from a place of cultural enlightenment to a popular landscape where cultural innovation and new wave ideas are provoked by resisting dominating power. From literati’s resisting power on secretly selling banned political books against the government’s dominating power on restricting the political views received by the public during the Martial Law Period to the minority groups’ resisting power on protecting their rights against the mainstream’s dominating power on defining the ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ in the modern days, the place has precisely showed the struggle of knowledge and rights between the two parties. Throughout the struggles, the bookstores representing each party present a phenomenon of creating and constructing new communities, new culture and new identity, thus enriching the significance behind the Wen-Luo-Ting community.

3. Empirical Analysis

Intersection of Culture and Context by an Imbroglio of Traces

The formation of Wen-Luo-Ting can be traced back to the 1960s. In the 1960s, Guling Street was famous for street second-hand stalls all over the street. At that time, due to the rise of stalls, local police officers would like them to make a change from placing all the goods on land to placing the goods on shelves next to the walls for the sake of road safety. Till 1974, to address the traffic issues at the level crossing of the North-South Railway Line, the Guanghua Bridge was constructed, with an integrated market beneath it. Vendors from Guling Street were relocated to operate in Guanghua Mall, with the basement level primarily housing used bookstores. However, Guanghua Mall was removed afterwards, some second-generation bookstore owners relocated their shops near universities. This is the predecessor of Wen-Luo-Ting. It shows a natural transformation of the sense of place according to time. Wherever the second-hand book vendors relocate, that will become the book hub, attracting book lovers or treasure diggers to gather there, demonstrating the spatial practice of a cultural landscape. Besides, it is an event-controlled space, the vendors and book stores are significant to the mentioned spaces, the core value of the geographical meanings is based on people’s activities and footprint, constituting a socially produced space. With different roles, people will view them or these districts with different views, the government saw them as the ones causing chaos, while the general public saw them as a treasure box, reflecting a process of place-making and the politics of space.

Talking about Wen-Luo-Ting nowadays, it has a high density of book stores and cafes, and also a university hub (Hsu, 2007). Through time, the image of these book stores have a huge difference, from a place where poor people love to buy books from, to a highbrows’ hub due to the relocation and people’s perspective on second-hand books. The most famous bookstore there is Tangshan Bookstore, also known as the “underground book kingdom”, selling books in the humanities and social sciences. Back the June 12 Restriction (六一二大限) in 1992, when foreign copyrights became legally protected in Taiwan, they also published many unauthorised translations of scholarly works in these fields. It was once a hub for banned books, a key platform for student works, including both written and audiovisual pieces, that were not viable for mass production (Multitude.asia, 2017). Therefore, to hide from the government’s checking, they chose to locate the store underground. Its underground architectural style has not changed till today, after the recreation of the district by the government. It is a reflection of the values of the Taiwanese government, which would like to emphasise freedom of speech and would like to alert people to the difficult time by keeping its original design, a form of counter-geography. This explores how power produces knowledge and normalizes standards, and how resistance is inherent to power, manifesting itself through the struggle over discursive power, embodying the tension between space and power.

Photo of 唐山書店 taken by groupmate at Wen-Luo-Ting

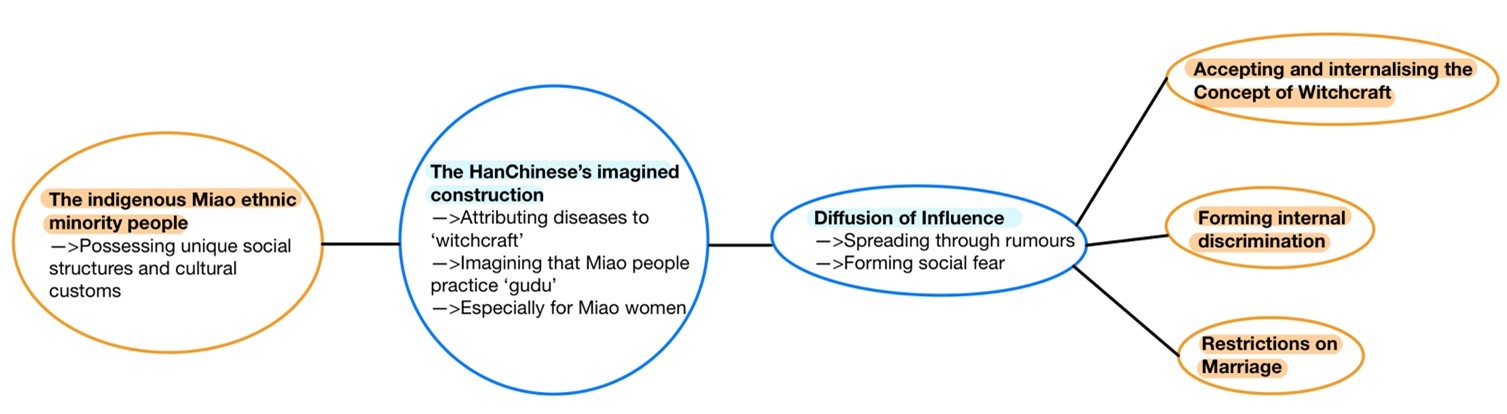

Representative of Resisting Power Throughout the Time

During the Japanese rule from 1895, Taiwan was politically and socially suppressed by Japan. As the goal was to turn Taiwan into an industrial hub for supplying various resources to Japan (Xiu, 2018), multiple attempts were made to forcefully adapt Taiwan to the "Japanese style", thus the heavy suppression of opposing ideas. This included the Taipani Incident in 1915 which massacred hundreds of Taiwanese who attempted to rebel (Chen, 2012); and the publication of the Chian-keisatsu-hou (1900) which seriously infringed the freedom of assembly and freedom of speech of the locals. Due to the heavy suppression, the urge for oppression has heightened.

Afterwards, the Kuomintang retreated to Taiwan and since then, Taiwan has entered a period of white terror under the authoritarian rule of the Kuomintang (Chen, 2012). Meanwhile, the National Taiwan University has been a hub for elites and intellectuals, creating an academic neighbourhood around the university. Therefore, the Wan-Luo-Ting area in the neighbourhood has become essentially a safe haven for these intellectuals to gather. Bookstores in the community have also started to sell books that are censored, or those which are considered avant-garde around the community of political elites.

The Wan-Luo-Ting area has become a symbol of political rebellion and free-thought since and therefore has been a place filled with independent bookstores with their respective ideologies. These ideologies often differ from the mainstream, for instance the Feminist bookstore Fembooks, Left-wing Ton San Bookstore and Christian Campus Books (Lam, 2007). These bookstores have maintained to be the symbols of free-thought since the formation of the district.

4. ConclusionThis study reveals Wen-Luo-Ting as a complex cultural community which identifies emerging geological factors ,and cultural resistance with the unrelenting pursuit of forbidden knowledge and marginalised voices. The concept of place as an “imbroglio of traces” (Creswell, 2006) and Foucault’s theory illuminate how traces—underground bookstores, banned-book legacies, feminist and left-wing shelves—are actively showing that resisting power is everlastingly challenging the dominating power, from Martial Law-era secret sales to contemporary minority struggles.

This paper shows the social construction process of the modern urban cultural landmark. To safeguard the vitality of such a unique community, the government should protect independent bookstores through providing financial support or strengthening the heritage status, resisting modern gentrification that might affect counter-hegemonic traces. Besides, it is essential to actively support minority-run spaces, ensuring the district remains a living laboratory of freedom. Only by preserving its traces can Wen-Luo-Ting continue to produce new identities and knowledge for Taiwan’s future.

Anderson, J. (2010). Understanding Cultural Geography: Places and Traces. New York and Oxon: Routledge.

Christensen, G. (2024). Three concepts of power: Foucault, Bourdieu, and Habermas. Three Concepts of Power: Foucault, Bourdieu, and Habermas, 16(2), 182–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/17577438231187129

Creswell, T. (2006).《地方:記憶、想像與認同》.(王志弘、徐苔玲譯). 台北:群學.

陳信安. 2012.《以文化觀光思維建構「1915 年焦吧哖事件」文化路徑紀念場域之研究 》. 行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計劃.

陳銘城,2012,秋蟬的悲鳴:白色恐怖受難文集,新北市,國家人權博物館籌備處.

大蔵省印刷局(官報). 1900. 法律治安警察法. 日本マイクロ写真出版, 東京. 10.11501/2948297

林欣靜. (2007, September). 溫羅汀獨立書店風景. 台灣光華雜誌 Taiwan Panorama | 國際化,雙語編排,文化整合,全球華人的雜誌. https://www.taiwan-panorama.com/Articles/Details?Guid=ef5801d7-e6ce-4291-b7da-e7c1a82bcb41&CatId=8&postname=%E6%BA%AB%E7%BE%85%E6%B1%80%E7%8D%A8%E7%AB%8B%E6%9B%B8%E5%BA%97%E9%A2%A8%E6%99%AF&srsltid=AfmBOorp0XW1DrPyHFpDlgND8atixtl5tHvwZgDyVh_NuMHSqBcTB_FV

Multitude.asia. (2017, September 22). 如果我盜版到一百種的時候…| 唐山書店陳隆昊訪談 (二) [Video].

王 泰升. 2004. 植民地下台湾の弾圧と抵抗 日本植民地統治と台湾人の政治的抵抗文化. 札幌学院, 訳者 鈴木敬夫.

Xiu, C. (2018, April 20). A Multi-Perspective Analysis of the Japanese Factor in the Taiwan Issue. Interpret: China. https://interpret.csis.org/translations/a-multi-perspective-analysis-of-the-japanese-factor-in-the-taiwan-issue/

徐詩雲. (2007). 當代文化階層的地方認同競逐:「公館�溫羅汀」〔碩士論文,國立臺灣大學〕. 華藝線上圖書館. https://doi.org/10.6342/NTU.2007.03053

1. Introduction

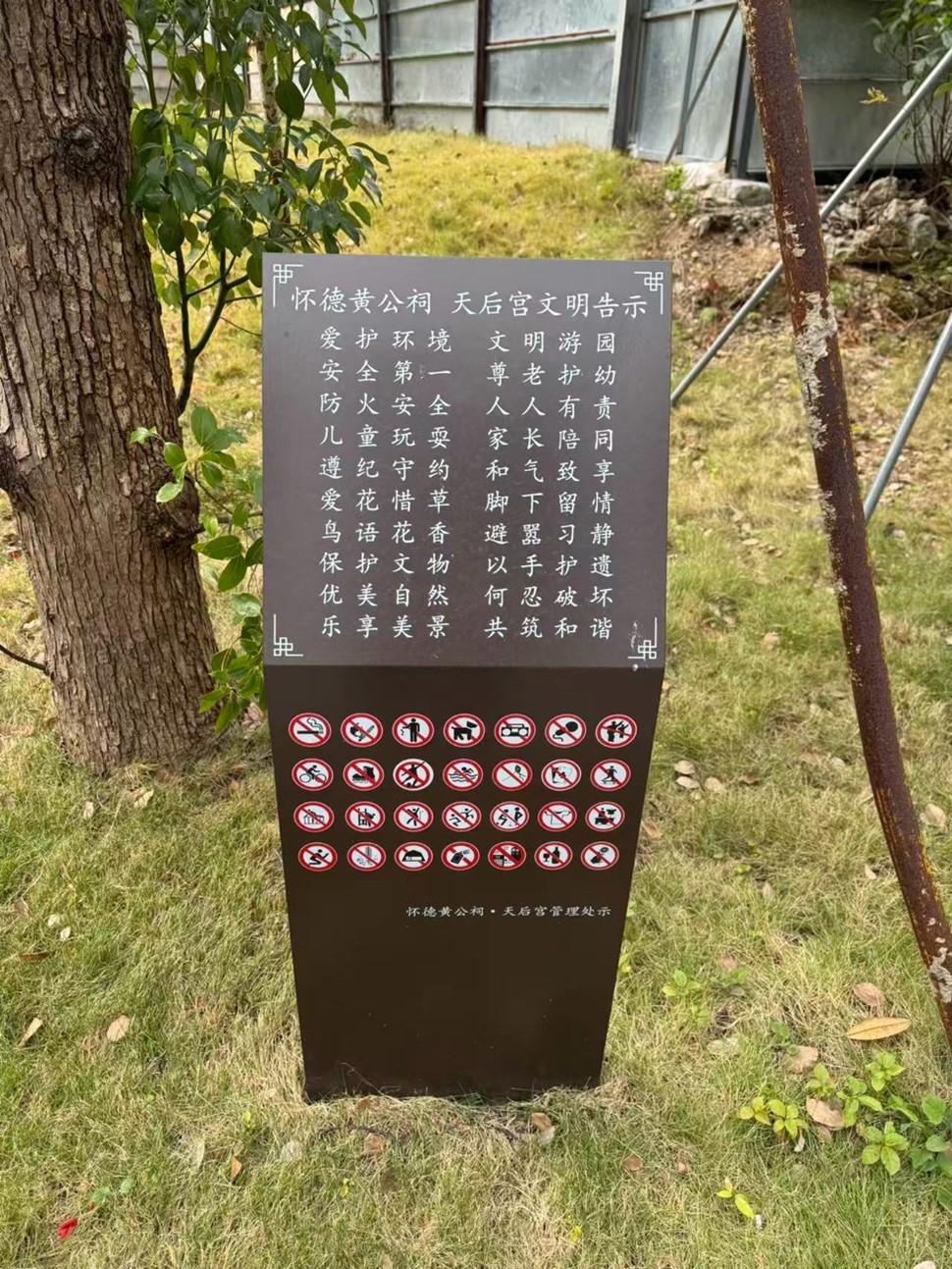

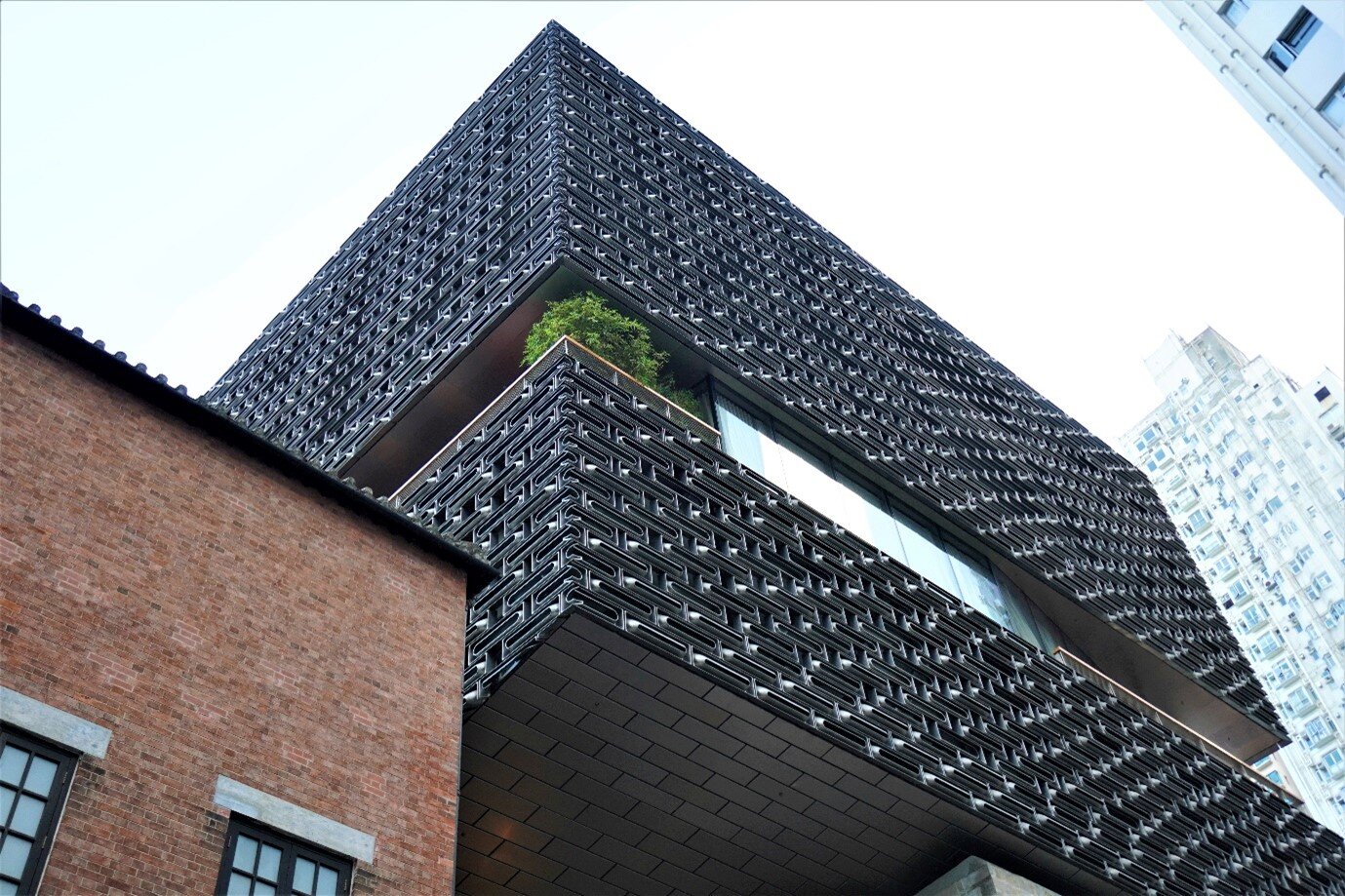

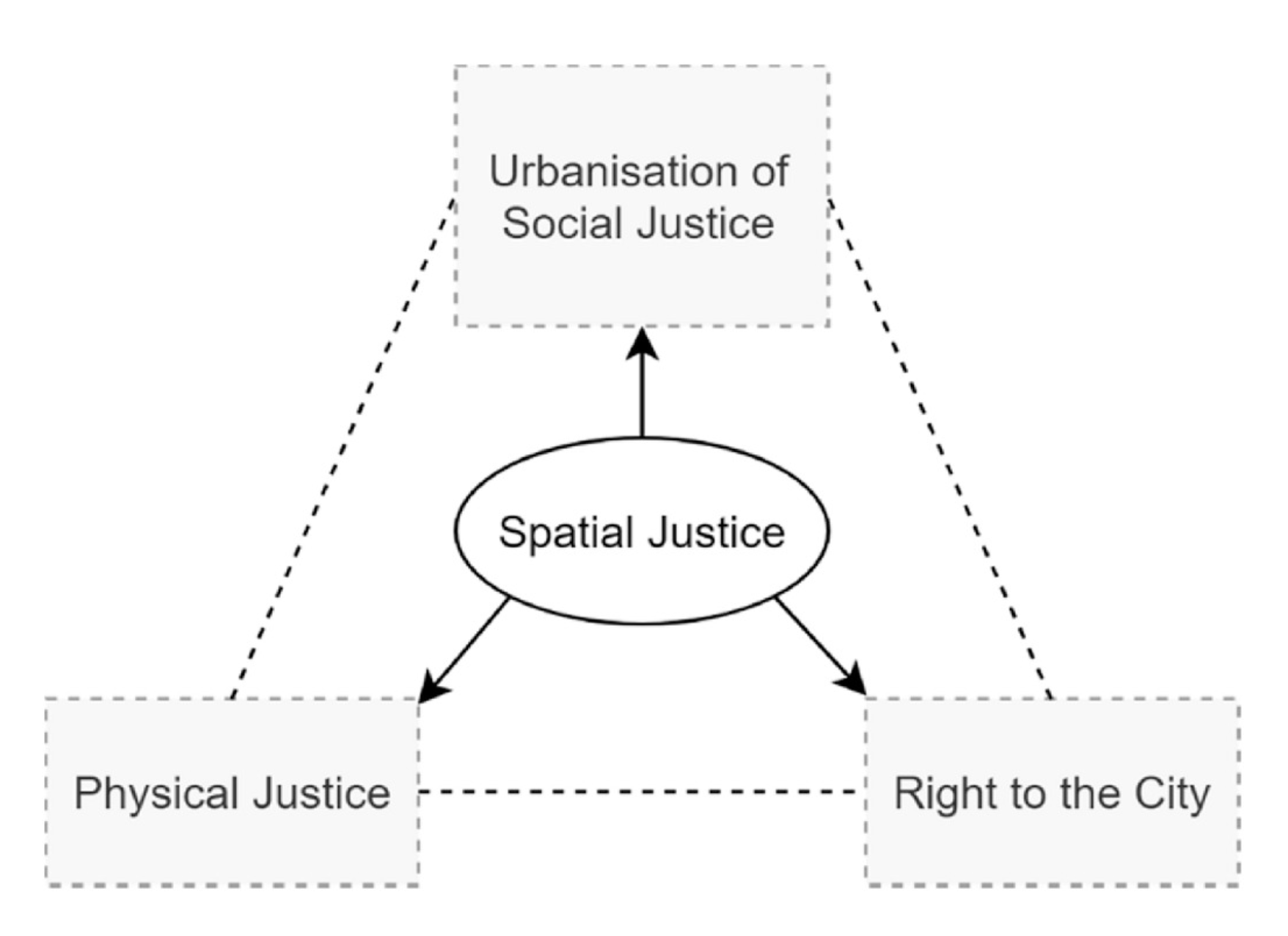

This project examines the Huang Gong Temple (怀德祠), an ancestral temple in Shangxia village, which now sits encircled by the soaring high-rises of the Zhongzhou Binhai Huafu residential complex in Shenzhen. This phenomenon deserves attention because it represents a profound and increasingly common cultural trace in China’s rapidly urbanizing landscape: the physical preservation but contextual transformation of sacred, historical sites. The temple, as a cultural trace, manifests the dramatic interaction between the grassroots, lineage-based culture of the original village and the powerful forces of state-led urban redevelopment. This project draws upon the cultural geographical concepts of spatial encapsulation and the everyday production of space to analyze how this unique spatial arrangement reconfigures the temple's meaning, transforming it from an exclusive site of clan worship into a contested, shared public space for the new urban community.

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

Cultural geography posits that space is not a neutral container but a social product, constantly being shaped by power relations, cultural practices, and everyday life. It focuses on how meaning is inscribed onto space, turning abstract "space" into meaningful "place." This project employs two key concepts to analyze the Huang Gong Temple:

- Spatial Encapsulation: This refers to the process whereby a traditional cultural space is physically preserved but simultaneously dominated and re-contextualized by a new, dominant spatial form—in this case, the modern residential complex. It is not merely being nearby, but being physically and visually surrounded and dominated. This process exerts a powerful symbolic force, often marginalizing the original significance of the encapsulated space and subjecting it to a new visual and functional logic (D. Harvey, 2002).

- Everyday Production of Space: Drawing on Henri Lefebvre's (1991) theory, space is continuously produced through everyday practices and social interactions. The meaning of a place is not fixed but is constantly negotiated through how people use it. The act of residents bringing children to play, of neighbors socializing, or of the elderly exercising in the temple grounds constitutes a form of "spatial practice" that actively produces new meanings, potentially challenging or layering over the temple's original sacred function.

Our analytical framework illustrates how the temple's meaning changes. First, its traditional atmosphere is weakened as it becomes physically surrounded by towers. Then, the daily activities of the community inject new, mundane functions into it. Together, these two processes create an internal tension between the temple's sacredness and its secular, everyday role.

3. Empirical Analysis

The Geographical Context: From Village Enclave to Urban Island

The Huang Gong Temple is located in the Futian District of Shenzhen, a city synonymous with hyper-speed urbanization. The geographical context crucial to this phenomenon is not just the city, but the specific process of "urban village" (城中村) redevelopment. Shangxia village was once a distinct entity, with the temple at its social and spiritual core. The construction of the Zhongzhou Binhai Huafu complex represents the latest and most physically overwhelming phase of this redevelopment. The temple was not demolished; instead, it was strategically preserved and isolated as a green-space centerpiece within the master plan. This has radically altered its context: once the heart of a horizontal villagescape, it is now a low-rise, traditional-form island in a vertical sea of modernity, accessible only by passing through the gates and curated landscapes of the private residential estate.

The Cultural Strands: Clan Lineage vs. New Urban Community

Two primary strands of culture interact at this site. The first is the clan-based lineage culture of the indigenous Huang family. For them, the temple is a "place" in the Yi-Fu Tuan (1977) sense—a space filled with profound meaning, history, and emotional attachment through generations of ancestor worship and collective memory. It represents continuity, identity, and sacred order.

The second is the culture of the new, heterogeneous urban community residing in the high-rises. This community, largely composed of middle-class professionals and migrant families, lacks historical ties to the temple. Their culture values amenities, leisure, and convenient communal spaces. For them, the temple ground is primarily a "space"—a accessible, aesthetically pleasing "central park" that serves practical needs for recreation and socialization.

Source: Photo by author, 2025.11.19

The Cultural Trace: Negotiated Sacredness in an Everyday Landscape

The preserved Huang Gong Temple is a clear trace of the negotiation between the original geographical context (the village) and the cultures that shaped it, and the new context (the luxury estate) and its culture. The preservation itself is a testament to the resilience of clan identity and possibly the developer's strategy to add cultural capital. However, the trace now tells a more complex story.

The temple's aura is fundamentally altered by its spatial encapsulation within the high-rises. These towering structures constantly dwarf it, serving as an overwhelming reminder of a new socio-spatial order. This power dynamic pressures its sacredness, potentially reducing it to a mere decorative artifact in the eyes of the new community.

Concurrently, the everyday production of space by the new residents actively rewrites the temple's script. When children use the courtyard as a playground, the primary sound is no longer of chanting but of laughter and games. When parents and domestic helpers gather there to socialize, the space functions as a living room for the community. These practices, while not intentionally disrespectful, impose a layer of secular, mundane meaning onto a space designed for reverence and ritual. This creates a quiet but palpable tension. One might observe clan members during Qingming Festival performing solemn rites amidst the casual comings and goings of residents, a stark illustration of the coexistence and collision of two different "place-making" processes.

This case reflects a modern urban dilemma: how to preserve a heritage site's soul, not just its shell. The temple stands intact, yet its original function and emotional impact are being gently yet profoundly altered. We witness its identity shifting from being a vessel of collective memory to an amenity for collective consumption.

Figure 5. A bronze moral lecture artwork in the temple compound.

Source: Photo by author, 2025.11.19

4. Conclusion

This project's application of a cultural geographical perspective reveals that the preservation of the Huang Gong Temple is only a partial victory for cultural heritage. Its meaning is not static but is dynamically and continuously reshaped by its new spatial and social context. We found that spatial encapsulation symbolically marginalizes the temple, while the everyday production of space by the new community overlays it with a secular identity, leading to a negotiated and layered "place meaning" that balances between sacredness and secularity. Reflecting on the concepts used, Lefebvre's triad proved invaluable in highlighting the conflict between the "representation of space" (the planner's and developer's vision of a preserved relic) and "representational space" (the lived, everyday experience of the residents). A key policy recommendation would be to move beyond mere physical preservation. Facilitating dialogue between the Huang clan and the new residents, and perhaps co-creating interpretive signage or shared cultural events, could foster mutual understanding and a more conscious, collaborative production of this unique space's future meaning, ensuring its historical depth is not entirely erased by its new everyday life.

Figure 6. The government-issued heritage placard.

Source: Photo by author, 2025.11.19

References

Harvey,

D. (2002). Spaces of capital: Towards a critical geography. Routledge.

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The Production of Space. (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.). Blackwell Publishing.

Tuan, Y. (1977). Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. University of Minnesota Press.

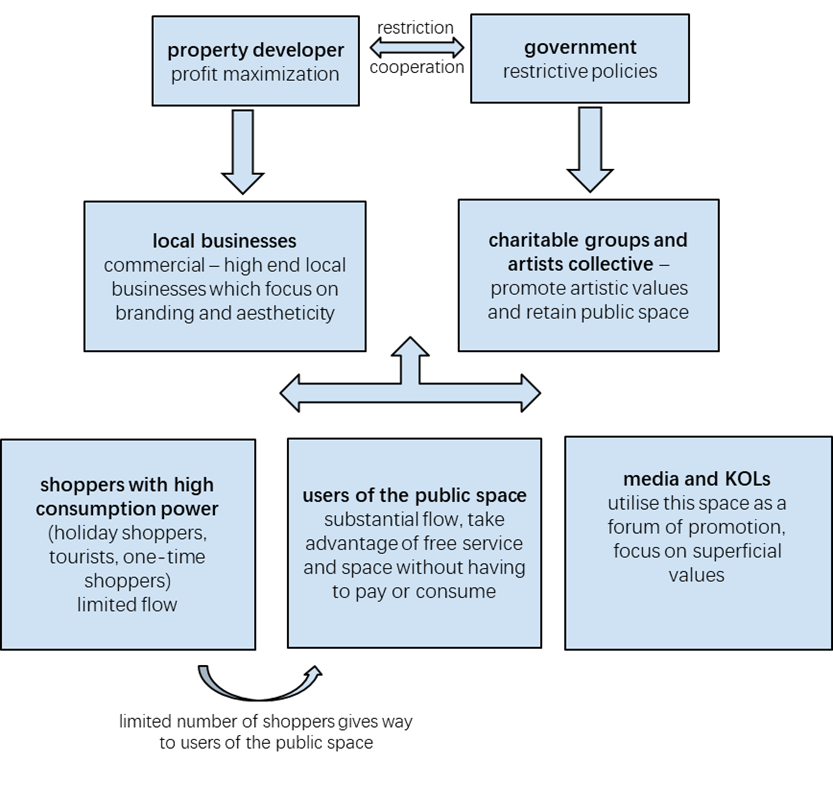

1. Introduction

This project investigates how everyday economic exchanges in Chun Yeung Street in North Point generate a distinctive form of cultural hybridity between Hokkien immigrants and the average Hong Kong resident. We will be investigating the scrutiny of the hybrid linguistic, spatial and commercial order that exceeds the simple differences between Hokkien and Cantonese. The marks of past migration and ongoing contact between these two groups can be traced as it is all recorded in the buildings, shop signs, voices and foods that are found on this street.

Figure 1 Chung Yeung Street

(Source: Taken by authors on 20/11/2025)

Geographically, Chun Yeung Street is located within a dense, lower income district shaped by small shops and limited public planning, the long standing Hokkien community combined with Minnan values of kinship and hard work created the conditions for frequent and repeated interaction with Hong Kong’s market oriented and Cantonese dominant urban culture.

The

project will draw on the concepts of cultural space and ethnic cultural

geography to analyze the links between place and culture. Chun Yeung Street is

treated as a contact zone where buying and selling is an everyday occurrence.

The multilingual conversations and the local adaptation of Fujian cuisine

connects geographical context with cultural ideas and value systems. Through

decades of routine practices, new hybrid cultural forms are continuously

created and maintained in the daily life of the street.

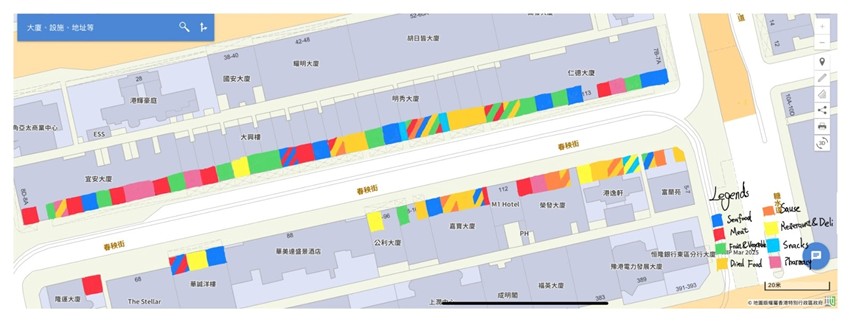

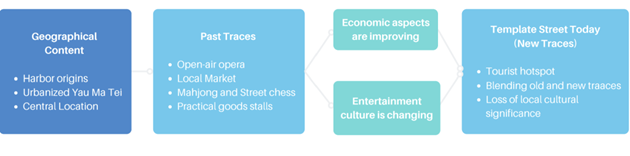

Figure 2 Type of shops on Chun Yeung Street

(Source: Geoinfo Map, 2025; noted by authors on 23/11/2025)

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

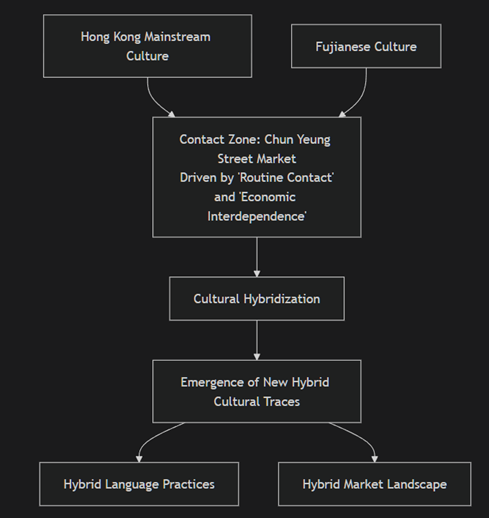

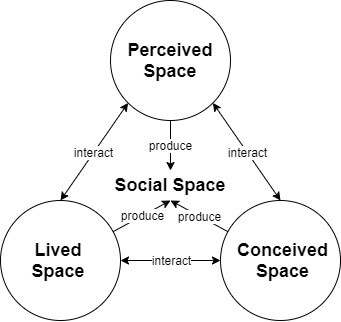

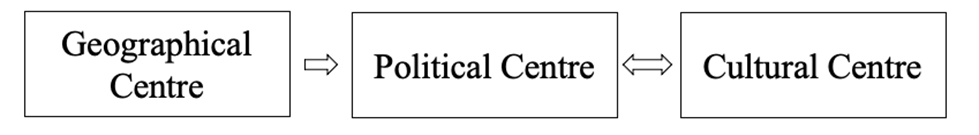

Cultural geography examines how culture and geographical context interact to produce "traces" and cultural landscapes. It focuses on the evolution of culture in space as well as how space constructs cultural identity and interaction.This project will use the following two core concepts: the first is cultural space, where Chun Yeung Street serves as a physical and symbolic arena for cultural interaction. The second is ethnic cultural geography, referring to the spatial clustering of Hokkien immigrants in North Point and the persistence of their culture. This study is based on the cultural hybridization theory by Peter Burke(1937). The core of this theory lies in posits that when different cultures meet in a specific space they do not simply assimilate one another or maintain a pure opposition, instead, they blend to create a new hybrid cultural form with its own vitality.

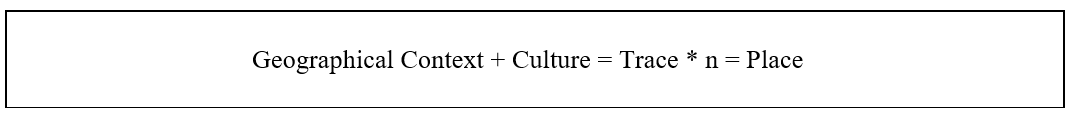

Figure 3 The research stream of the project

The analytical framework is as follows: Chun Yeung Street, rooted in the ethnic cultural geography of the Hokkien community, functions as a cultural contact zone. Through daily interactions and transactional relationships, and driven by the process of cultural hybridity, Hokkien culture and mainstream Hong Kong culture intermix here. This leads to the formation of a unique cultural landscape where both language and commercial practices exhibit distinct hybrid characteristics.

3. Empirical Analysis

The cultural integration phenomenon of Chun Yeung Street is mainly due to its unique geographical environment and cultural interaction. From a geographical perspective, this approximately 200-meter-long neighborhood located between Tong Shui Road and North Point Road in North Point is a microcosm of the about 400,000 Hokkien who are people in the Eastern District, mainly speaking the Hokkien language, who live in Hong Kong. It was developed by Fujian merchant Kwik Djoen Eng in the 1920s and 1930s. Therefore, the street is named by his first name in Cantonese spelling. (Wikipedia Contributors, 2012) The interwoven architectural form of Western-style buildings and high-rise buildings, along with the commercial ecosystem that includes clothing vendors, food shops and Hokkien cuisine restaurants, jointly form a material space that carries cultural interaction and serves as a spatial anchor point for the cultural geography of the Hokkien ethnic group.

Figure 4 Multi-cultural backgrounded merchants on Chun Yeung Street

(Source: Taken by authors on 20/11/2025)

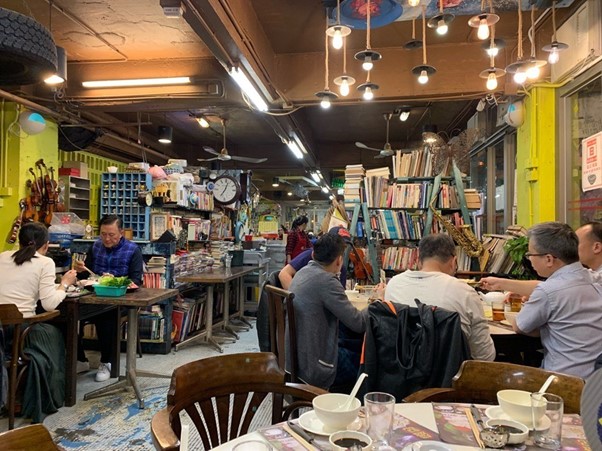

Our team visited two places run by Hokkien immigrants. Chin Chin Cuisine is a restaurant opened by a Hokkien immigrant (around 60-70 years old), and its dishes are largely similar to those from their homeland. The owner and staff communicate in Hokkien, while customers vary in their language usage. The authors visited the restaurant (November 20, 2025), and communicated in Hokkien. Four other customers were there, two speaking Hokkien, one speaking Cantonese, and one speaking both languages. The Cantonese speaker was the loudest and dominated the conversation. The authors also visited Bao Dim Tat Yan, where the owner and staff were younger (around 40-50 years old). They mainly use Cantonese, but can also use Hokkien. We also noted other shops and stalls selling Hokkien snacks on the street.

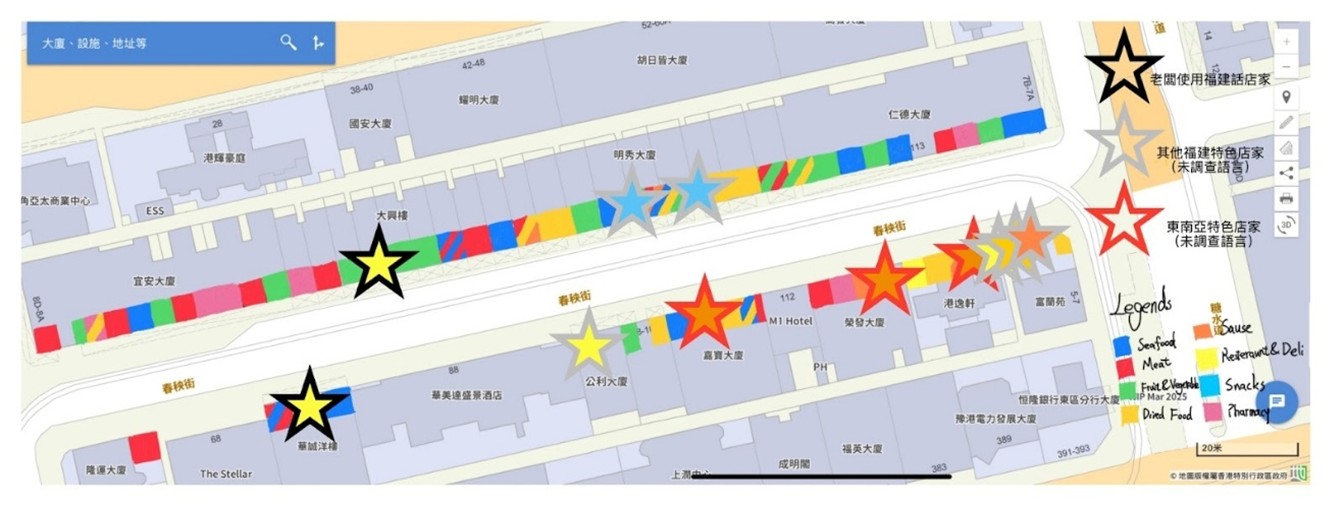

Figure 5 Language and cultural backgrounds of shops on Chun Yeung Street

(Source: Geoinfo Map, 2025; noted by authors on 23/11/2025)

In terms of cultural exchange, the interaction between the Southern Min language (Hokkien language) culture and the Cantonese culture of Hong Kong is a core factor. Immigrants from southern Fujian mostly use Hokkien, also known as Southern Min dialect, which is widely spoken in southern Fujian such as Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, Xiamen, as well as in Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and other places. In ecological research of the Southern Min dialect in Hong Kong by Xu Yuhang (2020), the Hokkien language in Hong Kong has undergone a great many special variations through long-term contact and interaction with Cantonese immigrants. Meanwhile, the restaurants and markets in Chun Yeung Street, as cultural contact areas, have become the medium for the interaction between Hokkien culture and Hong Kong culture in this environment. Trams also play an important role in the local community (Hong Kong Tourism Board, 2025), which indicates the dominant impact of Hong Kong Culture to residents.

This interaction between geographical context and culture has given rise to cultural hybridization through daily contact and economic interdependence mechanisms. Hokkien old merchants, the younger generation of Hokkien, Cantonese and consumers from other ethnic groups all participated together. In daily interactions, the older generation of merchants still use the mutated Southern Min dialect when running their shops, while younger customers or those of non-Fujian descent respond in Cantonese or Mandarin. The coexistence of the three languages on Chun Yeung street at present is the "trace" of cultural contact. As a result, the Hokkien spoken by Hokkien people in Hong Kong often bears Cantonese influences and differs from the language spoken by Hokkien people in their ancestral homeland (Xu, 2020). Many syllables are pronounced differently from those in their native region. Under the economic interdependence, Hokkien characteristic shops rely on the consumption demands of diverse ethnic groups to survive, and consumers also depend on these shops to obtain cultural products such as Minnan ingredients and Fujian cuisine. For instance, Hokkien cuisine restaurants will retain the core flavor of southern Fujian while making minor adjustments to the taste of their dishes to suit local diners, thus creating a hybrid of food cultures.

Figure 7 Introduction of Chin Chin Cuisine

(Source: Taken by authors on 20/11/2025)

The most impactful language to Hokkien, Cantonese, has dominated Hong Kong society since the establishment of Hong Kong's education system. Then, the languages of schools have been limited to English and Cantonese (Ding, 2013). During the movement to make Chinese the official language, Chinese became the official language of Hong Kong, Cantonese gained official recognition, while Hokkien did not receive enough attention and was gradually replaced by Cantonese (Ding, 2013; Ho, 2024). Hokkien characteristics were also incorporated into Cantonese, becoming one of the origins of the lazy pronunciation phenomenon (Ding, 2013).

The unique Hokkien culture of Hong Kong is also facing the challenge of being difficult to pass on. Cantonese, as the dominant language in Hong Kong, holds a dominant position in interactions. The variation and retreat of the Southern Min dialect essentially reflect the compromises made by Hokkien immigrants to adapt to mainstream society. Some linguists like Xu Yuhang believe that this imbalance in language power is manifested in the weakened understanding of the Southern Min dialect among the younger generation, which is a difficulty in the inheritance of Minnan culture (2020). Chun Yeung Street has gradually developed from a single space for Hokkien ethnic culture into a place for the exchange of diverse cultures. Its business form and cultural expression have become a model of Hong Kong's multiculturalism, and also reflect the transformation of the ethnic culture of immigrant cities from marginal to integrated.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, Chun Yeung Street mixes Shanghai and Hokkien Culture into Hong Kong local culture. It illustrates a path of integration where cultural identity is not eliminated and transformed through negotiation and mutual adaptation. But it has encountered some problems in cultural inheritance. We use the local cultural space and ethnic cultural geography as the traces to research the history and culture of Chun Yeung Street. To enhance the cultural influence of Chun Yeung Street in Hong Kong, the government could support local cross-language transmission to resolve the problems. For example, the government may fund community-based Hokkien and Shanghai dialect programs to protect the local Minnan culture and release some advertisements of Chun Yeung Street to make more people notice and get involved in the unique colorful hybrid culture.

References

Ding, P.

S. (2013). Hong Kong as a Laboratory for Language, Nationalities

Research in Qinghai, 24(4), http://doi.wanfangdata.com.cn/10.3969%2fj.issn.1005-5681.2013.04.030

Ho, J. C.

(2024). Hong Kong Anti-colonial Nationalism during the Chinese Language

Campaign. The China Quarterly, 258, 384–399. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741023001534

Hong Kong

Tourism Board. (2025). Chun Yeung Street (Wet Market). https://www.discoverhongkong.com/eng/interactive-map/chun-yeung-street-wet-market.html

Peter, B.

(1937). Cultural Hybridity. Polity Press. https://archive.org/details/culturalhybridit0000burk

The

Government of the Hong Kong SAR (2025). Geoinfo Map. The Government of the Hong

Kong SAR.

Wikipedia

Contributors. (2012, August 3). 春秧街. Wikipedia.org; Wikimedia