The Place of Politics

Introduction

Situated at the heart of the country, Beijing represents more than just the geopolitical centre of the Chinese regime, but also a longstanding historical origin and a melting pot of multi-ethnic cultures. As much as any other developments, the rise of Beijing as the capital city and a cultural hub for "Jinpai" (京派) and New Beijing culture has significantly transformed the city's landscape where these changes are strongly associated with its geographical context. In the following, we seek to understand why Beijing was chosen as the capital city and how it is related to Beijing's distinct cultural traces and practices.

The Making of a Capital City

The capital city, as described by Spate (1942), can be interpreted as a physical manifestation of the power of the state and, though not invariably, the cultural pole of the country. Geographical forces that configured and altered the course of cultural-political history are hence expressed intensively in the development of the capital city and are evidenced by both material and non-material traces. In no case is the complexity of factors regulating the selection of capital city more distinctly represented in that of Beijing metropolis. Despite its poor geographical settings away from the southern region and inaccessibility to the coastal areas and natural resources, Beijing has still been designated as the geopolitical centre since the Yuan dynasty due to various intricate political, military, and economic concerns.

Since the Ming dynasty, the expansion of national territory into Mongolia, Tibet and Manchuria has been as one of its offshoots the deposition of Beijing – a crucial gateway where the earlier invaders had dominated the Chinese empire (Spate, 1942). Its strategic location in the northern plain, thereby, enables the containment of threats from the Russian and other invaders along the northern borders. The relative proximity of Beijing to Manchuria, Mongolia and Tibet also played an essential role in maintaining friendly relationships with their local leaders for consolidation of the political power (Barmé, 2012).

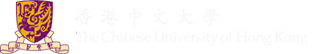

A topographic map of Beijing and its surrounding area

Reprinted from "Upgrading a regional groundwater level monitoring network for Beijing Plain, China", Zhou, Dong, Liu & Li, 2013, Geoscience Frontiers, 4(1), p.127-138

Beijing's distinct geomorphology, including mountain ranges as well as the Liaoning and the Shandong Peninsula, acts as a natural barrier to protect the city from foreign invasions. The rugged topography at Yanshan Mountains (燕山山脈), coupled with the Great Wall of China, provides natural defences against the armed forces of Mongolia along the northern borders (Chang & Liang, 2013). Despite attempts in restoring other cities, such as Nanjing, as the capital after the 1911 Revolution, their geopolitical locations were far inferior to Beijing owing to their vulnerability to foreign invasions and bombardment. The Japanese occupation in the 1930-40s, for example, reflected the problems of Nanjing and hence urging the state to relocate the capital city back to Beijing after the communist revolution in 1949. Therefore, owing to these geographical advantages of locating capital in the north in terms of uniting power and national security, Beijing was designed to be the geopolitical centre of China for many decades.

The Old Beijing culture: Traces of Imperiality and Hierarchy

Owing to the longstanding imperial and capital status, the Old Beijing city was constructed to represent not only the secular imperiality and authority but also the centre of the kingdom (Hershkovitz, 1993). As Wheatley (1971) described, "(Beijing represents) the point of ontological transition at which divine power entered the world and diffused outwards through the kingdom" (p.434). Hence, the city was carefully planned to resemble cosmographic principles according to the orthodox Chinese beliefs and rituals which benefit the consolidation of political power (Hershkovitz, 1993). Feudal ideas such as social hierarchy, centrality and male supremacy, which originated from the traditional Chinese philosophy of Confucianism and Taoism, were also expressed prominently and morphologically in the Old Beijing landscape. These transformations have constituted a significant influence on the urban landscape since the Ming dynasty and can be represented by the architectural styles of the Forbidden City (紫禁城) and siheyuan (四合院) – the homes for royal families and commoners respectively.

A Hu Tung (Old Beijing Lane) in Beijing (Photo by zhang kaiyv/ CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Forbidden City: Imperiality, Centrality and Hierarchy

Functioning as the political and ritual centre of China for more than 500 years, the Forbidden City offers a great glimpse into how these traditional values of imperiality, centrality and hierarchy were morphologically expressed in the heart of the capital city. Spatial hierarchy and centrality were closely represented in the spatial design and organization of the Old Beijing city and the palace. These constructions strictly followed the hierarchy ranks advocated in feudalism and Confucianism regarding the emperor as the highest position in the social hierarchy. The palace was rectangular in shape and was enclosed by cardinal walls and a south-facing gate known as Tiananmen. Within the palace, the Hall of Supreme Harmony (太和殿), the Hall of Central Harmony (中和殿), and the Hall of Preserved Harmony (保和殿) were constructed along the central axis and divided the palace into boxes of "outer court" and the "inner court". Outside the palace was another rectangularly walled district enclosing the entire palace called the "inner city". This complex boxes-in-a-box model delimits the ideas of spatial hierarchy and centrality as well as the solemn and majestic role of the emperor (Barmé, 2012; Hershkovitz, 1993).

A bird's eye view of the Forbidden City (Photo by Danny History & Ancient Cash Coin on Pinterest/ CC BY-SA 3.0)

The hierarchical ordering of space in Tiananmen also emblematizes the organization of political power of the regime. Tiananmen, the southern ceremonial passageway to the imperial palace, was closely accentuated by a series of watchtowers and guards. South of the gate was a T-shaped walled open space. The centre of the open space was a covered walkway known as Thousand Step Galley "Qianbulang" functioning as the venue for inspecting papers from candidates in public examination Keju (Hershkovitz, 1993). Behind the walled open space were the offices for government officials. These constructions symbolized a continuum of spaces of a gradual decline of sacrality with distance from the centre (ibid.).

Siheyuan: Spatial hierarchy and Feng Shui

The "Old Beijing" traces are strongly influenced by the local customs and traditional Chinese values such as social hierarchy and feng shui (風水). These cultures can be exemplified by the architectural styles of siheyuan (四合院). People are greatly influenced by Confucian values, respecting the elderly and ancestors, and Taoism, believing in a cosmic force that governs everything. Therefore, houses are built orderly in a rectangular arrangement and around water well in the middle. Its layout manifests the difference in status and the idea of 'superiority of seniority' (長幼有序), where the closer in family relationships and the older are prioritized. Planting mulberry (桑椹樹) and pear trees (梨樹) in the siheyuan are also considered as taboo for Old Beijinger since they are homophonic to the word "death" (喪) and "separation" (離) ("Lao Beijing", n.d.). All these values originate from Confucius and Taoism, showing a dynamic relationship between people and space. This also explains the famous saying that "Beijing people constructed Siheyuan, and meanwhile, Siheyuan shaped the Beijing people" (北京人建造四合院,四合院塑造北京人).

The entrance of a siheyuan in Beijing (Photo by vnwayne fan/ CC BY-SA 3.0)

Post-communist revolution (1949) and transformation of New Beijing

The massive transformation of Old Beijing culture took place when the communist party seized power. While representing revolutionary ideologies and patriotic resistance to the imperialist rule, the communist regime was placed in a paradoxical position after their victory in the Chinese Civil War. Their rise in power challenged whether the historical monuments, such as the Forbidden City, Tiananmen and siheyuan, which emblematize the lingering hegemony of the Chinese imperial rule, could be retained in the New Beijing city (Hershkovitz, 1993). Transforming these conflicting tokenisms, therefore, was urgent and pivotal to the legitimization of the communist regime giving rise to a New Beijing culture since 1949 (Hou, 1986).

Tiananmen was first to be reimagined and reconciled according to the communist image and concepts of New Beijing and New China. The former "T"-shaped open space was cleared of trees and expanded into Tiananmen Square, which further articulates the new spatial centrality and legitimacy of communist rule by introducing the Great Hall of the People and the Museum of the Chinese Revolution to the western and eastern side of the area (Hou, 1986). The tokenism of historical exclusion and hierarchy, such as walls and gateways in the inner city, was dismantled for introducing ideas of openness and inclusiveness of the new regime. A massive portrait of Mao on top of the central gateway of Tiananmen was added to reinforce the transformation into New Beijing.

On the other hand, traditional Old Beijing rituals and values as represented by siheyuan had undergone major transformations under the influence of New Beijing movements. While socialist industrialization prevailed in the city, residential districts were often attached to workplaces to form work unit compounds. Many standardized nondescript low-rise apartments built were influenced by socialist planning theories which advocate equity and equality (Hui, 2013; Yan, 1990). Experimental neighbourhoods were also planned with a commune cafeteria instead of individual kitchens for each apartment to reinforce the communist ideologies of cohesiveness and collectivism (Yan, 1990). The upholding of socialist architectural symbolism in residential planning had significantly reshaped the old city's landscape while marginalizing the importance of heritage conservation and the Old Beijing culture (Wong, 2015; Yan, 1990).

Under such context, the "Liang-Cheng Proposal", which envisioned an urban future by redirecting economic development to newly expanded areas while preserving the vibes of the ancient city, was formulated to counter with state's attempts in redeveloping the old city. The idea, however, was rejected by the state due to its strong emphasis on western planning theories and contradictions with the socialist imaginations of the New Beijing city and New China (Wong, 2015). It was not until the 1990s that the legacies of Liang and Cheng are re-emphasized in the Chinese planning system as evidenced by a more sensitive approach in the planning to protect the city’s heritage.

Reference

Barmé, G. (2012). Forbidden city. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Chang, Z. Q., & Liang, Y. C. (2013). Cong lishi dili de hongguan mailuo kan zhongguo yu beijing ─ guanyu gudu wenhua de duihua. Wenhua zhongguo, 77(2), 4-14.

Hershkovitz, L. (1993). Tiananmen Square and the Politics of Place. Political Geography, 12(5), 395-420. doi:10.1016/0962-6298(93)90010-5

Hou, R. (1986). The transformation of the old city of Beijing, China. In M. P. Conzen (Eds.), World Patterns of Modem Urban Change (pp. 217-239). Chicago: University of Chicago, Department of Geography.

Hui, X. (2017). Housing, Urban Renewal and Socio-Spatial Integration. A Study on Rehabilitating the Former Socialistic Public Housing Areas in Beijing. A BE (Delft.), (2), 1-796.

Lao Beijing. (n.d.). Retrieved August 03, 2020, from https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E8%80%81%E5%8C%97%E4%BA%AC/8388502?fr=aladdin [Lao Bei Jing. (n.d.).]

Ouroussoff, N. (2008, July 23). Lost in the new Beijing: The old neighborhood. Retrieved August 03, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/23/arts/23iht-27ouro.14711541.html

Spate, O. H. (1942). Factors in the Development of Capital Cities. Geographical Review, 32(4), 622. doi:10.2307/210000

The Forbidden City, China. (n.d.). Retrieved August 03, 2020, from https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/south-east-se-asia/china-art/a/forbidden-city

Wheatley, P. (1971). The Pivot of the Four Quarters: A Preliminary Enquiry into the origins and Character of the Ancient Chinese City. Edinburgh: Edmburgh University Press.

Wong, S. (2015). Searching for a modern, humanistic planning model in China-The planning ideas of Liang Sicheng, 1930-1952. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 32(4), 324-345.

Yan, X. Y. (1990). Human impacts of changing city form: a case study of Beijing [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Michigan]. Dissertation Abstracts International 51-04A.

Zhou, Y., Dong, D., Liu, J., & Li, W. (2013). Upgrading a regional groundwater level monitoring network for Beijing Plain, China. Geoscience Frontiers, 4(1), 127-138. doi:10.1016/j.gsf.2012.03.008

Place of Spatial and Ideological Competition

Introduction

Politics oftens shapes the culture and space of a place, and this is particularly obvious in Shanghai. For over a century, Shanghai has experienced intense clashes of values as it changed hands among multiple powerful interests. Apart from sending Shanghai's economy onto a roller coaster ride, these clashes have let Shanghai with a cosmopolitan cultural landscape, where traces of competiting values are juxtaposed against and fused with each other.

The Bund, Shanghai (Photo by Yujie Liang)

Geography of Shanghai

Shanghai lies at the middle of China's eastern coast, near the estuary of the Yangtze River. It is bordered by the Yangtze River to the north, the East China Sea to the east, Hangzhou Bay to the south, and Jiangsu and Zhejiang Provinces to the west. Moreover, Shanghai is a populous city. Not only is Shanghai the largest city in China by population about the second most populous city proper in the world. In 2017, the population of it was as many as 24 million.

The origin of Shanghai culture – Wu culture and South Yangtze culture

Shanghai's culture can be traced back to the regional culture of Yangtze River Delta – Wu culture (吳文化). The origin of Shanghai culture can be traced back to Pre-Wu Culture, which was developed in Primitive society and prospered in Zhou (周) to West Jin (西晉). As a result, Wu culture has a profound influence on Shanghai culture. For example, Shanghai people’s favoritism of art could be attributed to Wu culture.

During Jin to Qing, as the capital city of Jin moved south, Shanghai became an immigrant city flooded with immigrants with the majority of them from Zhejiang. The immigrants from Zhejiang brought South Yangtze Culture (江南文化) into Shanghai. This culture is marked by a combination of rationality (i.e. being pragmatic and emphasizing benefits) and romance (i.e. valuing artwork and attaching importance to moods and feelings). These two values have set the undertone of Shanghai culture.

The culture of Shanghai in colonial period – Shanghai School

Towards the final decades of Qing, Shanghai’s culture underwent rapid transformation. Since 1845, British, American and French successively established their concession (租界) following the defeat of Qing dynasty in the First Opium War. The culture of Shanghai then incorporated Western culture from United Kingdom, France, Russia, America, Jewish culture and Eastern culture from Japan. It would not be exaggerated to claim that nearly all major modern cultures were converged in Shanghai.

Political milestones of modern Shanghai: From late Qing to socialist China (by Anson Tsui)

Both Protestant and Catholic culture were thus introduced into Shanghai. The former emphasized instrumental rationality (i.e. rational calculation of cost and benefit and pragmatism). On the other hand, the latter culture featured art and romance. In this period, the traditions of South Yangtze Culture met the two Religious cultures and merged with them. The tradition of rationality integrated with Protestant culture into a unique culture of rationality and pragmatism in Shanghai. The romance of Shanghai people was also blended with Catholic culture. For example, the Protestant culture reinforced the hard-working of Shanghai people.

Absorbing different culture, Shanghai developed its distinctive culture – Shanghai School (海派文化). Shanghai School consists of diverse, heterogeneous cultures which are inter-diffusing and inter-contradicting. For instance, there were “local – foreign”, “Eastern – Western” and “rationality – romance” conflicts occurred in the same time. The heterogeneity of Shanghai School made it difficult for people to understand Shanghai School with merely the perspective of either China traditional culture or Western traditional culture.

Moreover, after the Opium War, Shanghai became China’s first industrialized city. Backed by Yangtze and being the intersection of freighters from south and north, it was an ideal place for the foreign companies to do business. The influx of foreign capital and technology made Shanghai undergo rapid industrialization.

Characterized as fashionable, modernized, Shanghai was an ideal city pursued by Chinese in late nineteenth century. At that time, Shanghai’s production was itself perceived by Chinese as a brand manifesting high quality. As a result, Shanghai school was also regarded as a modern culture.

Traces of Shanghai School – Chinese painting and Beijing Opera

While the common form of traces is material (i.e. building, signs or statues), they can also be non-material (i.e. rituals, activities or events). One of the outstanding traces of Shanghai School is Chinese Painting.

In 1851, evading from the chaos made by Taiping Heavenly Kingdom (太平天國), many painters and writers migrate to in Shanghai. At that time, the Shanghai School Chinese painting was gradually formed. Different from other painters, the major purposes of Shanghai school painters were profit-making. It in fact contradicted the traditional thought that the purpose of artwork was simply to express emotion. Moreover, one could easily find that the Chinese civil art and Western painting techniques were both embodied in their paintings. Greater form exaggeration and brighter colors were always used in the Shanghai school Chinese painting. Therefore, we could see that the “rationality – romance” and “foreign – local” culture conflicts of Shanghai school were demonstrated in Chinese Painting.

"After the poems of Da Mei" by Ren Xiong (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ren_Xiong#/media/File:Mjmhg009-renxiong.jpg)

Another trace of Shanghai School was a different version of Beijing Opera (京劇). Compared with the Beijing Opera in Beijing, the Beijing Opera in Shanghai was modernized. Different from traditional opera, scenery setting like the modern drama stage for performance was used. Shanghai school, as a modern culture, was incorporated into Beijing Opera.

Regime change in 1949 – the rise of socialism and the decline of Shanghai school

The People's Republic of China was founded in 1949. It was a watershed of the culture of Shanghai, in which Shanghai school was displaced by the new ideology, socialism. The change of ideology eventually led to the transformation of space. Under socialism, working class theoretically became the ruling class of the state. In a society transformed to embrace socialism, the capitalist space would not be accepted and tolerated. Accepting it means accepting the past political and social structure. As a result, Shanghai space became the resource contested in 1949.

As the communist leader aimed at eliminating the lifestyle of capitalist class, they transformed Shanghai from a commercial city into an industrial city. A strong communist municipal government established a new order of the city conforming to the central spatial planning of the government. Moreover, it underwent transformation of culture. There was no longer import of luxury. Facilities of entertainment such as brothel and nightclub were closed.

Transformation of space – The Bund

The rapid ushering in of communist ideologies was reflected in the transformation of Shanghai’s consumer space into productive space. One of the traces demonstrating the change of culture is The Bund (上海外灘). Shanghai Bund used to be the British concession since 1844. In that period, it was occupied by the most powerful British companies such as Jardine Matheson & Co. (怡和洋行). Moreover, as Shanghai was one of the trading ports under the Treaty of Nanking (南京條約), many foreign companies moved into this area. In short, Shanghai Bund before 1949 could be regarded as the center of Western power in China.

The most modernized part of the city, the Bund was populated with entertainment facilities. After 1949, they were considered as the symbol of capitalism, which contradicted to socialism. As a result, they were soon transformed into other usage. For example, the HSBC Bank Building was transformed into the building of municipal government. As we could see, the building representing the old symbol was transformed and given a new symbol.

Shanghai Xintandi becomes a very popular area today. (Photo by Yujie Liang)

The change of ideology – Shanghai Xintiandi

As Michel Foucault put it, space are symbols of ideologies (Elden, 2016), embodied in buildings and thus play an important role in political and economic strategies. Henri Lefebvre (1991) also added that the nature of space and the production of space is political. It means that space is always contested by different ideologies. Shanghai Xintiandi (上海新天地) is a trace captures the changes in ideology. Moreover it also shows the combination of East and West, tradition and innovation, by converting a century-old Shikumen District (石庫門) into a region of vitality.

In colonial period, Shikumen was one of the most distinctive buildings in Shanghai. Its western architectural style represented the encounter of eastern and western culture. It is the earliest symbol of the penetration of western culture into the daily lives of Shanghai people. The architecture of Shikumen also represented the urbanization process of Shanghai, in which the traditional Chinese culture began to undergo transformation. Living in a limited space, citizen had to learn to become pragmatic and sophisticated. For example, the structure of Shikumen originated from Siheyuan (四合院), incorporating the traditional concept of ‘superiority of seniority’ (長幼有序). On the other hand, it adopted some western architectural styles as to use the space in an efficient way. This mentality, in turn, contributed to Shanghai School.

The Door of a Shikumen Building in East Siwenli before demolished. (Photo by Livelikerw / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Since the 19th century, evading the rebellion of Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, an avalanche of immigrants from other cities fled to Shanghai. The demands of houses like Shikumen, then, increased. In 20th century, as the rents in Shanghai were so high that Shikumen became a popular option for citizens. However, after 1951, Caoyang New Village (曹楊新村), a residential area for working class, was built. At that time, Caoyang New Village, embodying socialism, became the typical architecture of Shanghai. In other words, it reflected the ideology of the ruling socialist government.

In 1978, the situation was changed again when the China central government launched the economic reform. As to reintroduce capitalism, Shikumen district was transformed into a consumption area, Xintiandi. In fact, the establishment of Xintiandi could be seen as the revival of the mercantile culture of Shanghai. Under the transformation by Shanghai government, it became a trendy place in Shanghai, with various foreign brands moving in it. Therefore, capitalist ideology was manifested in it again.

Today, this district becomes a heterogeneous space. Although it incorporates some trendy elements, it also preserves its nostalgic part, such as the structure of the buildings. While foreigners may consider Shikumen as representative traditional Chinese culture, the local may see it as an expression of western cultures. This heterogeneity was also the constituent part of Shanghai School. More importantly, it was a monumental architecture recording the change in ideology.

Reference

Elden, S. (2016). Space, knowledge and power: Foucault and geography. Routledge.

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Blackwell: Oxford.

Religious Culture and the Place of Belief

Introduction

Nestled between towering mountains and calving glaciers, Tibet evokes a lot of fascinations about what its loftiness and remoteness breed. Such fanciful interest is often directed at the spiritual aspects of Tibet as the origin of Tibetan Buddhism (藏傳佛教). In the following, we examine how Tibet has developed as a place of belief, where Tibetan Buddhism has held pervasive sway in the lives of the Tibetan people. Specifically, we examine how the emphasis of centrality and cyclic existence in Tibetan Buddhism are physically inscribed in Lhasa (拉薩), Tibet’s capital city.

Tibetan Buddhist Monks (Photo by Ani)

Nature, Bon and Tibetan Buddhism

Tibet is bounded on the north and east by the Central China Plain, on the west by the Kashmir Region of India and on the south by Nepal, India, and Bhutan. It is located on the Tibetan Plateau (青藏高原), where some the world’s highest mountain peaks, including the Himalayas (喜馬拉雅山), are found. With an average altitude of over 4,000 m, this highland area is often known as the ‘roof of the world’. The region is the source of many of the world’s most important rivers, including the Indian River (印度河), the Ganges (恆河) and the Mekong (湄公河).

Living in an ecologically diverse and challenging environment, indigenous Tibetan felt that their life was at the mercy of mother nature. They practiced a natural-based religion called Bon (苯教). They worshipped a wide range of natural phenomena and features – from sun, moon and thunders in the sky to mountains, rivers and animals on the ground – which they believed are inhabited or regulated by spirits.

Namtso, the heavenly lake of the Tibetans (Photo by Ani)

However, the dominating influence of Bon to Tibetans began to be challenged in 7th century, when King Songtsen Gampo (松贊干布) actively promoted Buddhism. Songtsen Gampo was known as a powerful leader who united the then various Tibetan principalities into a single kingdom. During his reign, many of Tibet’s highly civilised neighbours, such as Nepal, India and the Tang Empire, were Buddhist states. Observing the close links between Buddhism and the culture of his neighbouring powers, Songtsen Gampo decided to introduce Buddhism to Tibet to civilise his people and strengthen its kingdom (Sangharakshita, 1999). He started building Buddhist temples and promoting Buddhist teachings across Tibet.

The development of Buddhism in Tibet subsequently faced a long period of resistance from the Bon followers. They included the noble families whose power were undermined by the Buddhist kingship, and the Bon priests whose livelihood were threatened (Sangharakshita, 1999). It was not until the 11th century that, after successive rounds of social and political struggle, did Buddhism finally acquired dominance over Bon in Tibet. This however did not result in the complete erasure of Bon from the Tibetan cultural landscape. While inherited from India, the Tibetan practice of Buddhism has assimilated some of the domestic ideas and practices of Bon. This process of ‘indigenisation’ (本土化) has shaped Tibetan Buddhism into a distinctive branch of Buddhism. For example, Tibetan Buddhism retains the Bon worship of natural entities. Besides temples and buddhas, Tibetan Buddhists also pray to mountains and lakes accorded with sacred status, as well as mounds of mani stones (瑪尼堆) – stones inscribed with the six-syllable Buddhist mantra (六字真言) (Huang and Liu, 2010).

A mani stone mound along Nyang River, southwest Tibet (Photo by Wikipedia user 山海风 / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Centrality: From Worldview to Urban Layout

The worldview of the Tibetans is underpinned by the idea of centrality. According to Tibetan Buddhism, the universe is centred upon a mountain named Mount Meru (須彌山) (Samuel, 2012). The heaven of gods and demigods is located above the mountain, while the hell lies below it. Around the Mount Meru are continents and subcontinents where human beings live. Although this view of centrality was inherited from Indian Buddhist texts, it was not difficult for the Tibetans to find resonance with it – living on an almost boundless terrain, ancient Tibetans developed their sense of belonging and orientation around visually prominent features on their horizon (Huang & Liu, 2010).

Mount Meru, depicted on a piece of silk embroidery produced in the 18th century

(Photo from the Walters Art Museum / Public Domain)

The emphasis of centrality in Tibetan Buddhism has influenced the spatial organisation of settlements in Tibet. The development of Lhasa, Tibet’s religious, economic and administrative centre for centuries, assumes a radial pattern around a central point, namely, the Jokhang Temple (大昭寺). Built in the 7th century, the Jokhang Temple houses the Jowo Rinpoche, a statue of the Buddha at the age of 12. Since the statue was believed be blessed by the Buddha himself, Tibetans, as followers of Tibetan Buddhism, have enshrined the Jokhang Temple as their most sacred temple. Conforming to the principle of centrality, Lhasa’s main roads all radiate from the Jokhang Temple. Moreover, no buildings around the Jokhang Temple are allowed to be built taller than it so that it can be seen from anywhere in Lhasa.

Jokhang Temple (Photo by Wong Ting Kwan)

Circling of and in Life

Another central belief of Tibetan Buddhism is cyclic existence (輪迴), the idea that one would be reborn after his/her death. According to Tibetan Buddhism, life circulates between six worlds: (i) the heaven of the gods, (ii) the realms of the demigods who are at constant war with the gods, (iii) the world of human beings, (iv) the realm of animals, (v) the realm of the spirits fated to perpetual thirst and hunger, and (vi) the hell-realms with dreadful punishments of the cold and hot hells (Samuel, 2012, p. 91). The world to which one would be reborn is a function of the merit one accumulated during one’s lifetime. Following the teaching of Buddha, Tibetan Buddhism suggests, is the only way to prevent one’s successive rebirths in the undesirable worlds.

Tibetan Buddhists have figuratively incorporated the cyclic nature of their existence into their everyday rituals. As a symbol of their religious practice, Tibetan Buddhists regularly spin a prayer wheel (轉經筒), a handheld cylindrical wheel containing paper printed with mantras. They believe that spinning a prayer wheel allows people to accumulate the same merit as orally reciting the sutra. In many Tibetan temples, stationary prayer wheels are installed in a row, allowing people to turn the wheels one by one by sliding their hand over them.

Prayer wheel: A symbolic marker of Tibeten culture (Photo by Ani)

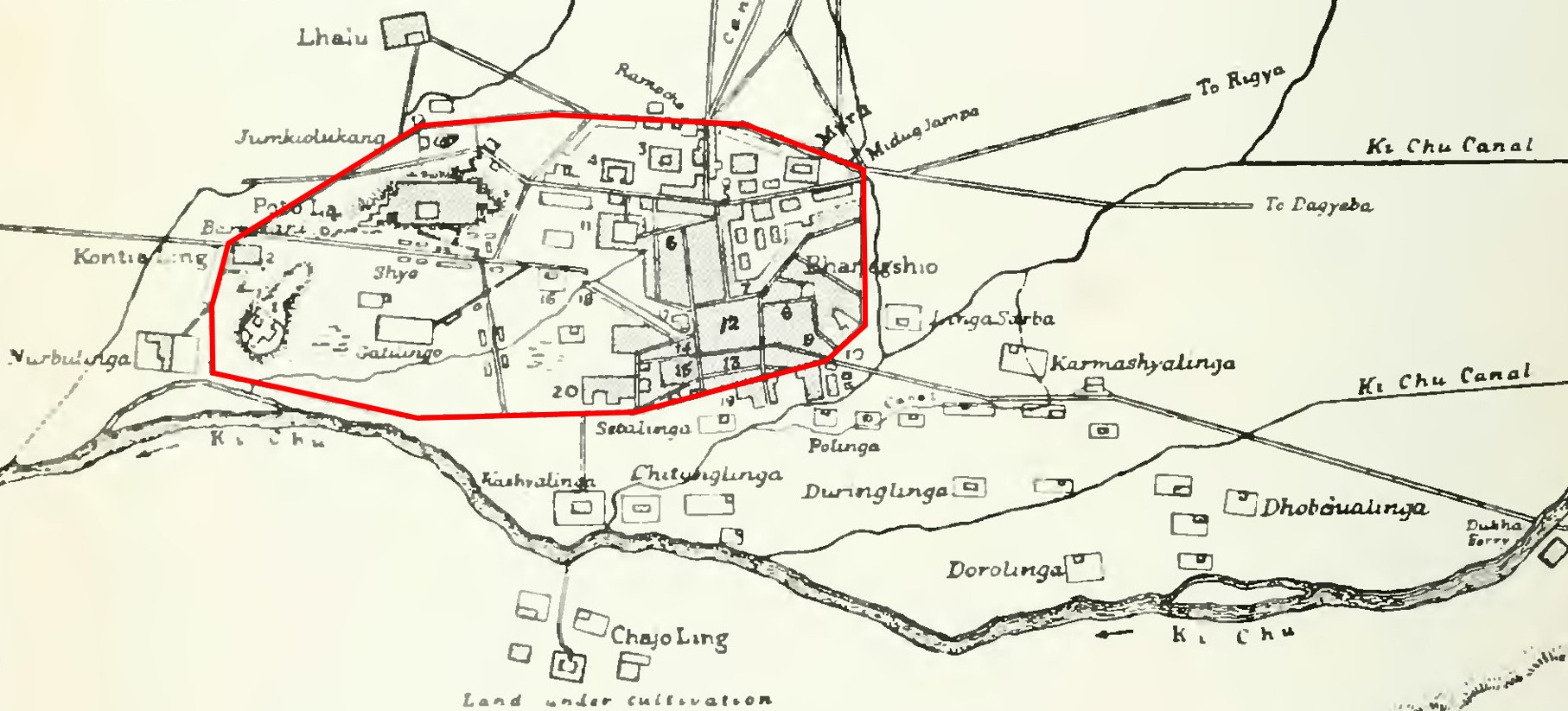

In Lhasa, Tibetan Buddhists also take ritual walks in a clockwise manner along the city’s three pilgrimage circuits. These circuits share the Jokhang Temple as their common centre – yet another illustration of the principle of centrality. The innermost circuit, the Nangkhor (朗廓), runs around the main hall of Jokhang Temple, where the Jowo Rinpoche is housed. The middle circuit, the Barkhor (八廊), circumscribes the Jokhang Temple. It was formed as a street along which pilgrims to the Temple and businessmen gathered. The outermost circuit, the Lingkhor (林廓), encircles the urban core of Lhasa. It takes people two to three hours to complete a full circle of walk.

Extract of a map of Lhasa drawn by Indian surveyor Kishen Singh in 1878. The circuit of Lingkhor in marked in red.

(Original image in Public Domain)

References

Huang, L. & Liu, C. (2010). The image-meaning relationship between Tibetan traditional architecture and religious culture [西藏傳統建築空間與宗教文化的意象關係]. Huazhong Architecture [華中建築], 2010(5), 134–137.

Sangharakshita (1999). Tibetan Buddhism: An introduction (reprinted with corrections). Birmingham, UK: Windhorse Publications.

Samuel, G. (2012). Introducing Tibetan Buddhism. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

The Intersection Between Geography and Ethnic Culture

The Mysterious Southwest

China’s southwest region has long fascinated anthropologists and ethnologists as an area of mysteriousness. Rolling mountains and meandering rivers have long isolated the region from the rest of the country, and masked its culture to the outsiders. In fact, the three provinces of the southwest region, namely, Yunnan, Guizhou and Sichuan, are homes to more than 30% of China’s 113.8 million ethnic minority population. These ethnic minority people contribute greatly to the heterogeneity of culture in the southwest.

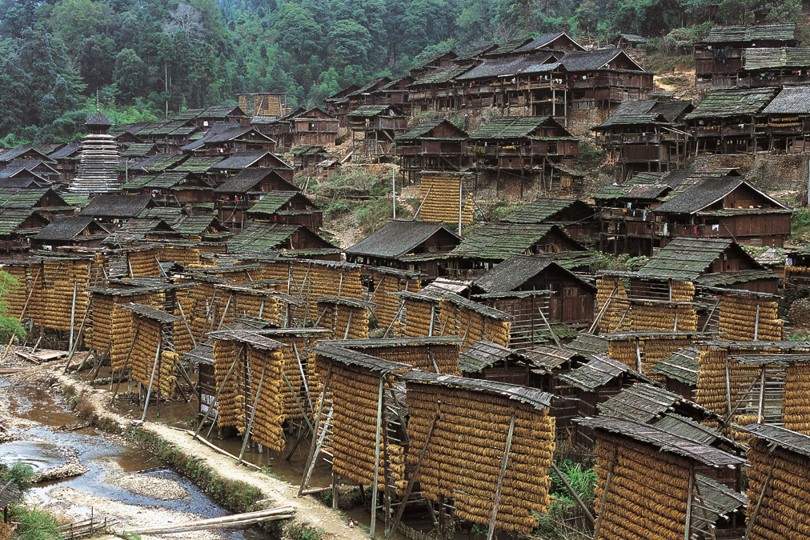

In recent years, tourism development has taken off in Yunnan and Sichuan, offering more opportunities for us to explore their rich cultural landscapes. On the contrary, as the least developed of the three provinces, Guizhou and its culture remains relatively below the radar of popular attention. Mountains and hills take up over 97% of Guizhou’s territory, holding back the development of its rich natural resources, and keeping its GDP one of the lowest in China. However, it is the same rugged terrain that spares the various ethnic groups in Guizhou from external disturbance, and helps preserve their diverse cultures.

Ethnicity, Geography And Guizhou’s Culture

Ethnicity, or ethnic group, is a key category of differentiation of human communities. As Jon Anderson (2005) puts it, ethnicity can be understood as an identity that emerges when a group shares a common ancestry, origin, and tradition. While it may be related to race, it may also be connected to geographical territory, worldview, custom, ritual, and language. Since each ethnicity has its unique set of culture, a place with more diverse ethnic composition tends to have more diverse cultures.

This is the case for Guizhou, where as many as 48 ethnicities reside in its territory. According to China’s 2010 national census, around 36% of the province’s 34.75 million population is ethnic minority, with a significant share of them from the ethnic groups of Miao (苗族) and Buyi (布依族). They make up as much as 11% of China’s ethnic minority population.

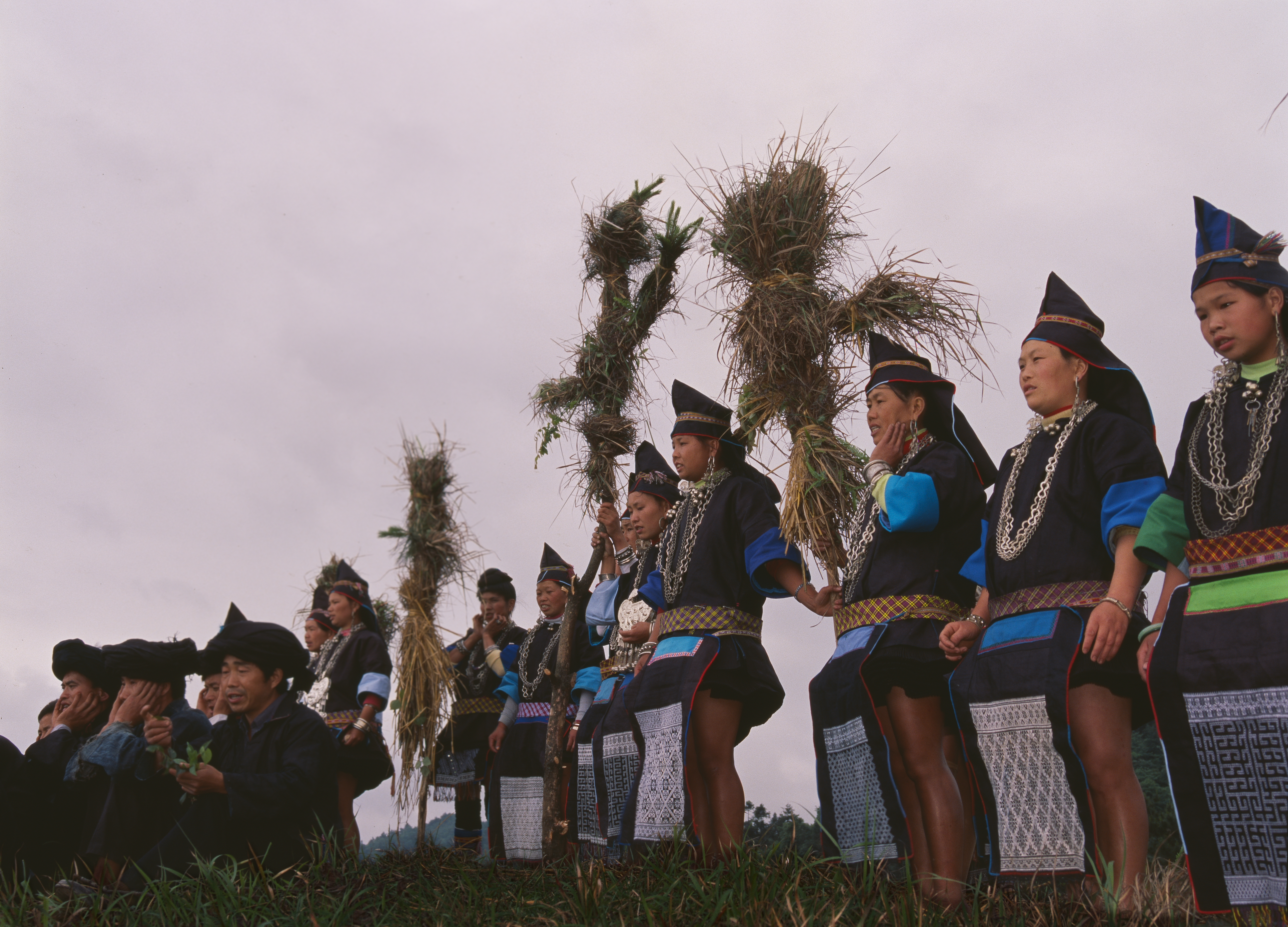

The Miao is a major ethnic minority group in Guizhou (Photo by Lu Xianyi)

Guizhou's geographical context shapes the development of these diverse ethnicities and their culture. Isolated by numerous rivers and mountains, each ethnicity retains a certain degree of territorial independence from each other, and develops its distinct set of values and cultural practices. These ethnicities therefore can co-exist in the province on an equal basis without serious cultural conflict. Neither culture was subordinate to the other and neither culture is dominant. Due to its plurality, Guizhou culture is often called the ‘Thousand Island Culture’ (千島文化).

Guizhou’s Culture: Diverse Yet Connected

Despite its plurality, Guizhou’s culture is not a set of loosely connected subcultures. Beneath the cultural differences between ethnicities lie two shared beliefs. The first one is animism (萬物有靈論), i.e. a belief that objects, places and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. It is the differences in what they worship that distinguish each ethnic groups. This also creates the difference between their rituals. However, though the worshiping objects are diverse, all of them was associated with the lifestyles of the ethnic groups. For instance, for the ethnic groups whose major activity is felling, trees are considered as the object to worship.

Another shared belief of Guizhou’s subcultures is fear. Ancestors of today’s various ethnicities in Guizhou were migrants from central China. The ‘long march’ they had was fraught with difficulties. Some are natural ones, like geological hazards and infectious diseases. Some are human ones, like conflicts with other people along their migration route. Therefore, their rituals usually manifest their fear of death, rivals, disaster, sickness, etc. Fear is the motivation of the nations to protect themselves as well as to develop their cultures.

Traces of Guizhou’s Culture 1: Mountains

Within all the traces, mountains are the most outstanding symbols in Guizhou culture. To Guizhou people, mountains are not merely a natural substance but also are endowed with specific meanings. They are the sites or objects for people to express their particular views on human-nature relations.

Guizhou is surrounded by mountains (Photo by Calvin Chung)

In fact, mountains have an important role in Guizhou culture because of people’s dependence on mountains for survival. Obtaining natural resources, such as foods and medicine, from mountains, people derived their mode of production and lifestyle from them. Moreover, mountains are also seen as a natural barrier to protect Guizhou people from invasions. As a result, people attach great importance to an intimate harmony between them and nature. This belief demonstrated in the rituals undertaken in the mountains to express their hope, such as worshiping the god of mountains. The linkage between the lives of Guizhou people and the mountains, in fact, represent the relationship between them and nature. Therefore, mountains are more than a natural substance. They are symbols representing saints worshiped Guizhou people.

Trees and house is another pair of traces showing the intimate relationship between people and the natural environment. The diverse mountain living environment creates various mountain communities. Suspended wooden houses are a typical building in Miao villages. Wooden houses are built on stilts a few meters above the ground along the mountain ridge.

Suspended wooden house embodies the intimate relationship between people and nature in Guizhou (Photo by Lu Xianyi)

Traces of Guizhou’s Culture 2: Silver

Silver represents the trace of costume. Females from the Miao ethnic group in Guizhou would wear heavy and elaborate silver headdresses and jewelry in various ceremonies. Traditionally a Miao woman cannot get married without wearing silver jewelry in her wedding outfit.

Silver takes special importance in Miao culture not only because it is a symbol of wealth. At the very beginning, the ancestors of Miao believed that silvery accessories could exorcise evil spirits and heal the diseases. As Miao was an ethnicity with a history of successive migration, silvers were brought in the journey and used in poison testing.

Today, silvers also symbolize the distinct identity and history of Miao. Lacking their own texts, Miao people used silvery costumes as the carrier of their culture as well as their history. Preserving the traditional silver arts, they serve to survive and transmit tribe culture from one generation to another.

Silvery costumes of the Miao people (Photo by Lu Xianyi)

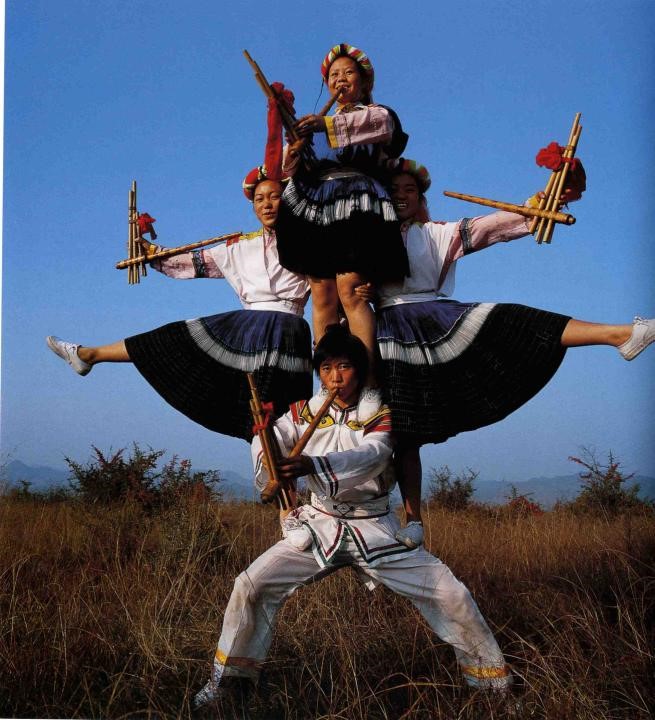

Trace of Guizhou’s Culture 3: Music and Dances

Just as the case of silver, lacking their own texts, Sheng (笙), songs, and dances the means to transmit their culture. In fact, Sheng is one of the earliest musical instrument in China, which nowadays is still widely used by ethnic folks in Guizhou, especially the Miao. Sheng and drum act as bridges between the present and the past, a media for conversations with the ancestor. Moreover, Sheng also associates with the geographical context of Guizhou. It is believed that in the primitive society, Sheng was used by Miao ancestors to attract their prey.

Singing and dancing are the two most pleasant symbols among ethnic folks in Guizhou. They are integral to the culture of these ethnic folks for thousands of years. As there is no text to help with the passing down of messages, singing and dancing are traces expressing ethnic outlook about the world, embodying the philosophical thinking related to the subsistence, reproduction, and development of the different minorities. In fact, the themes of music and dances in Guizhou are always related to their lifestyle and nature. For example, imitating animals is one of the common themes in dances.

Miao's traditional 'dragon dance' (Photo by Lu Xianyi)

Conclusion

In the case of Guizhou, we can see how culture interacts with geography. On the one hand, the culture of Guizhou is shaped by its environment. On the other hand, its culture also shapes its trace. Isolated by numerous rivers and mountains, diverse cultures were then preserved and manifested in various ceremonies and rituals. In the case of Guizhou, not only can we understand how the geographical context shapes the culture but also how rituals act as significant immaterial traces.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Mr. Lu Xianyi for providing us with the precious photos of Guizhou. Without his works, we could hardly present the beauty of Guizhou.

Lu Xianyi was born in 1958 in Guizhou. He changed his major from painting to photography in 1985 and went to Beijing in the early 1990s to work in the field of business portrait photography. Returning to Guizhou, he has been photographing the ethnic group of Black Miao for more than ten years. Lu is a representative of contemporary photographers in China, receiving numerous awards for his outstanding achievement.

China's Anti-Traditional Frontier

Introduction

Located at the southern coastal periphery of China, Lingnan (嶺南) is home to a regional culture which differs significantly from the mainstream Chinese culture originated in Zhongyuan (中原, literally ‘Central Plains’). Contrary to the conventional view of China as a closed nation built on agriculture, Lingnan culture has attached great importance on commerce and maintained a relatively open attitude towards foreign cultures.

Why is Lingnan culture so ‘anti-traditional’ (Liu, 1997)? How is its distinctiveness related to Lingnan's context?

Lingnan: Shielded by Mountains, Facing the Seas

Lingnan encompasses the

territories of today’s Guangdong (廣東), Guangxi (廣西) and Hainan (海南) provinces. However, the notion of Lingnan

culture is often used to refer specifically to its variant in Guangdong, the region’s

most prosperous and influential member in political-economic terms. Our

discussion of Lingnan culture here follows this specific definition.

Lingnan is separated from

its northern neighbours by Nanling mountains (南嶺). In fact, Lingnan in Chinese means the region

south of Nanling mountains. Before railways were available, one had to spend as

much as three months to travel from Zhongyuan to Lingnan. Nanling mountains did

not completely sever economic, demographic and cultural flows between Lingnan and

other parts of mainland China. However, they did limit the extent of assimilation

of Lingnan by the mainstream Chinese culture.

Meanwhile, Lingnan’s coastal location encouraged economic and cultural exchange between the region with the broader world. Facing the Pacific Ocean, Lingnan was the starting point of the Maritime Silk Road (海上絲綢之路). Flourished for over 1,500 years between Han and Ming dynasties, the Maritime Silk Road was an important maritime trade route connecting China and coastal states across Asia and Africa. Silk was exported from Lingnan through the Maritime Silk Road, in exchange for gems, ivories, spices, medicines and crafts.

Xianxian Mosque in Guangzhou, first built in Tang dynasty (Photo by Huangdan2060 / CC BY 3.0)

Traces of Lingnan culture 1: Lingnan Cuisine

The diversity of ingredients and cooking methods of Lingnan cuisine reflects the openness and internal variedness of Lingnan culture, which in turn is linked to the geographical advantages of Lingnan. Firstly, the richness in ingredients is one of the significant characteristics of Lingnan cuisine. It can be attributed to the abundant natural resources in Lingnan. Having a moderate climate, together with plentiful rainfall and sunshine, Lingnan is a place conducive to agriculture and farming. Not to mention the neighboring Pacific Ocean which provides Lingnan with abundant and diverse marine products. The diverse range of ingredients appears as a robust foundation of Lingnan’s food culture.

Moreover, Lingnan cuisine has long been influenced by foreign cultures. It is famous for being innovative, combining traditional Chinese and western culinary tradtions. Taking modern Cantonese cuisine (新派粵菜) as an example, it incorporates numerous western seasoning into traditional Cantonese cuisine, such as black pepper sauce and the British ‘OK’ sauce (a brown sauce which, interesingly, is no longer produced for the British market, but only sold overseas).

Black Pepper Beef Stir Fry: A Lingnan cuisine with western condiment (Photo by avlxyz / CC BY-SA 2.0)

Trace of Lingnan culture 2: Profit-seeking mentality/ Lindingyang bridge

Guangdong was the frontier and experimental field in Chinese economic reform (i.e. introducing market principles) (改革開放). Under the reform, Shenzhen, Zhuhai and Shantou were made three of the four earliest Special Economic Zones (SEZ) of China in 1979. Moreover, in 1984, Guangzhou (廣州) and Zhanjiang (湛江) became two of the first 14 coastal cities opened by the Chinese government to overseas investment.

The case of Chinese economic reform, in fact, reinforced the culture of Lingnan. Not only its openness to the Pacific Ocean but also its long-standing ‘profit-seeking’ mentality made Lingnan a desirable site to enact the economic reform. It is also important to note that, while complying the policies from central government, the major consideration of governments in Lingnan is their self-interest and their own prosperity.

Lindingyang bridge (伶仃洋大橋) was one of the outstanding traces of Lingnan culture. Since 1997, Zhuhai (珠海) government has started off the project of constructing Lindinyang bridge. However, though the first part of the project, known as Qi’ao Bridge, had received the permission from the central government, throughout the 1980s the planning work for Lingdingyang Bridge was done only by Zhuhai government. It was totally of the aspiration of the mayor of Zhuhai municipal, Liang Guangda (梁廣大). They even had not communicated with the Hong Kong government. The project was eventually forced to shut down after 3 years.

With further modifications, the proposal for a bridge to connects both sides of the PRD has evolved from Lingdingyang Bridge to today’s HK-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge.

Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao

Bridge (Photo by N509FZ / CC BY-SA 4.0)

The case of Lindingyang Bridge reflected the mentality of Lingnan culture. As the Lingnan region is geographically remote from central China, the central government always finds it difficult to govern it. Lingnan in turns enjoys great autonomy. As a result, they are used to loosely conforming to the central government and acting without permission. The case of Lindingyang Bridge was one of the traces manifesting the ‘act first, report later’ (先斬後奏) mentality rooted in Lingnan culture.

Conclusion

Geography always shapes cultures. By examining the geographical context of the Lingnan region, we can find the origin of its culture. The formation of the major characteristics of Lingnan culture could be attributed to its geographical isolation from central China. As a result of being separated, Lingnan culture became distinctive to traditional Chinese culture. In turn, it attached great importance to profit-seeking and incorporating different cultures. Today, one could still easily find the traces demonstrating these elements. The cases of Lindingyang Bridge and their roles in Chinese economic reform were the good examples manifesting their mentality and culture. While they were obligated to comply with the policies from central government, the own prosperity was their major concerns.

Today, Lingnan culture has become an influential cultural force in various international communities, and is the integral part of the culture of Hong Kong and Macau. It is because of the migration of the Cantonese people to Hong Kong and Macau, and in many oversea communities. On the other hand, due to its geographical context, Lingnan culture has absorbed different foreign cultures.

Reference

刘益. (1997). 岭南文化的特点及其形成的地理因素. 人文地理, 1, 46.

(2008,1月19日)。粤菜的前世今生。中國華文教育網。擷取自: http://www.hwjyw.com/zhwh/qywh/lnwh/yswh/200801/t20080119_10829.shtml

(2006,12月15日)。岭南饮食文化概述。中国经济网。擷取自:http://www.ce.cn/celt/ltzt/2006gdx/szgd/200612/15/t20061215_9774244.shtml

(2011,6月1日)。岭南地区的饮食文化——以广州饮食为例。新浪博客。擷取自:http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_6c1c658e0100rsp0.html