Havens of Traditional Widsom

Introduction

As bulldozers proceed apace to modernise and urbanise China, concerns are growing about the fate of the country's ancient villages. Most of the ancient villages that survive today were built during the Ming or Qing Dynasty, with a minority of them dating back to the Song Dynasty. These ancient villages demand our attention and protection because they are havens of traditional Chinese wisdom. They are tangible traces of how Chinese historically conceived of their society and their interaction with the surrounding environment.

Fengshui and Ancient Villages

Rooted in the idea of an integrated and holistic universe, fengshui is a set of traditional Chinese theory on how people can achieve a harmonious relationship with nature through careful planning and design of their built environment. Its emphasis on nature is obvious from its two constituent Chinese characters: while 'feng' means wind, 'shui' means water.

According to fengshui, nature is filled with qi (氣), an intangible form of energy which vitalises everything. Its flow is 'responsible for the retention or dissipation of anything', including 'health, wealth, fortune and intelligence of human beings' (Mak and So, 2015, p. 208). People can therefore lead a better life if they live at sites where qi is accumulated. As a result, the practice of fengshui is about locating and designing settlements with a view to maximise the level of qi for their inhabitants.

Fengshui forest at the back of a village in Lam Tsuen, Hong Kong (Photo by Chong Fat / CC BY-SA 3.0)

This thinking of qi gives rise to two principles which were followed in the planning and design of many ancient villages. The first principle is avoiding wind. Fengshui suggests that wind can blow qi away (Mak and So, 2015, p. 51). Since China experiences cold currents from the north in winter, it is better to locate villages in south-facing sites surrounded by mountains in the north. In so doing, villages can be shielded from the northerlies and can therefore retain qi better. On plains without mountains, fengshui recommends people to instead plant trees to the north of their villages as windbreaks to help retain qi. Forests grown for this reason are known as fengshui forests (風水林).

The second principle is finding water. According to fengshui, qi is kept and accumulated in water (Mak and So, 2015, p. 51). Resembling blood flowing in our body to keep us alive, water flowing in nature carry qi to villages for their people to thrive. As a result, ancient villages were typically built near a peaceful lake or a curving river enclosing them – fengshui identifies both features as conductive to the accumulation of qi. On the contrary, villages would avoid locating next to a straight river, which is seen in fengshui as flushing qi away.

Central pond in Hongcun, a village in Anhui first built in the Ming Dynasty (Photo by Mulligan Stu / CC BY 2.0)

Defence and Ancient Villages

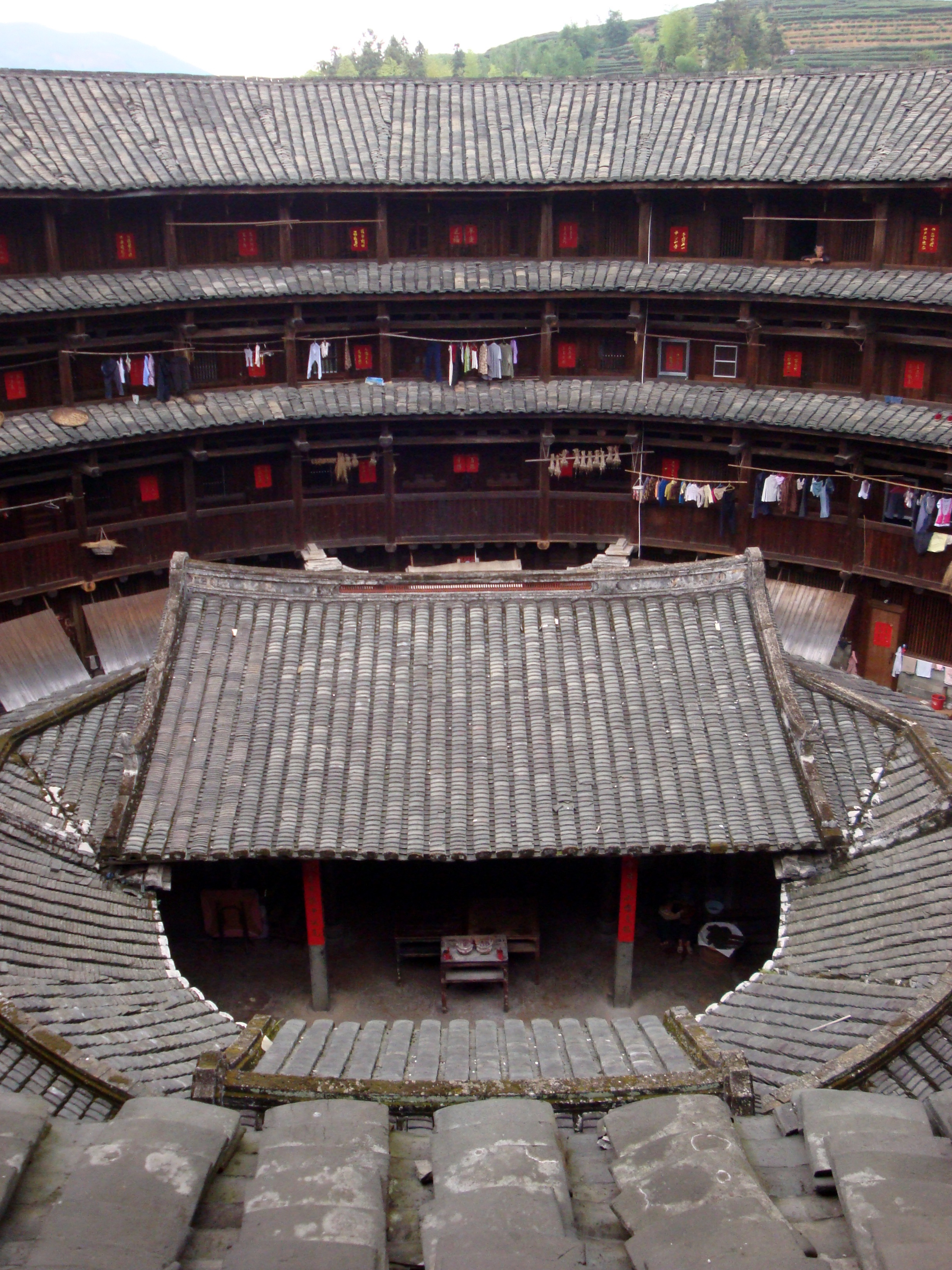

Apart from making peace with nature, ancient Chinese were also concerned about protecting themselves against threats from the outsiders of their communities, from local bandits to foreign invaders. Defence constitutes another important consideration in the planning and design of ancient villages. A famous example is tulou (土樓), or 'earthen dwellings', built by the people of Hakka (客家) in Fujian province.

The Hakka are Han Chinese whose ancestors migrated from the Yellow River Basin to south China to flee successive political and military conflicts in north China. This history is reflected by the very name of the Hakka, which literally means 'guest families'. As migrants, the Hakka were often in conflict with their indigenous neighbours over resources and territories. As a result, defence is a centrepiece of Hakka culture and is emphasised in the construction of Hakka settlements.

A tulou as seen from above (Photo by Gisling / CC BY 3.0)

A tulou consists of a collection of buildings surrounded by a massive wall of up to five stories. Its wall is built with rammed earth – from which tulou earns its name – and reinforced with multiple layers of iron plate, bricks, bamboo or other locally available materials. To prevent invasion, each tulou has only one entrance, and its lower stories do not have any window. At higher stories, some holes were drilled through the wall to shoot down attackers.

Defence is not just about building walls against external threats – it is also about promoting cohesion and mutual support among people living behind the walls. The centripetal internal layout of tulou is conductive to a communal spirit essential for security. Building within a tulou are often organised in concentric circles, with their doorways facing the centre. During an attack, this concentric organisation facilitate the recruitment of residents from across the tulou for defence. It also allows people to have easy access to food and water from the food storages and wells at the centre of the tulou. Also found at the centre of a tulou is a hall for social gathering and ancestral worship, which practically and symbolically promotes unity among everyone living around it.

Centripetal layout within a tulou (Photo by fisher0528 / CC BY 3.0)

Reference

Mak, M. Y., & So, A. T. (2015). Scientific feng shui for the built environment: Theories and applications. Hong Kong, China: City University of the Hong Kong Press.