Many of you may not be familar with the term 'cultural geography', or have even never heard of it. However, matters of cultural geography actually penetrate every bit of our life. To pin down what cultural geography is about, let us consider the two more commonly known words that make up of this term, ‘culture’ and ‘geography’.

What is Culture?

‘Culture’ is often a confusing notion to many people because it can be understood both narrowly and broadly. In a narrow sense, culture refers to the ideas, beliefs and attitudes which define the shared way of living of a group of people. An example of culture in this sense is the emerging idea that eating meat is unethical. Culture is viewed as a distinct sphere of life, separate from other spheres such as the political, economic, environmental and so on (Price, 2010: 635).

‘Meat is murder’, Barcelona, Spain (Photo by Bartek Miskiewicz / CC BY-ND 2.0)

However, culture can also be thought in a broader sense as ‘what humans do’ (J. Anderson, 2015: 6). It is not just about the abstract thoughts which regulate our lives, but also about the objects and actions which symbolise, reflect and consolidate these thoughts. These objects and actions are known as traces of culture. In this sense, the growing business of vegetarian restaurants which do not serve meat is not only an economic phenomenon but is also a cultural one. These restaurants are traces of the culture of meat consumption as an unethical practice. Culture in this sense is not independent from politics, the economy or the environment, ‘but influences (and is influenced by) them all’ (J. Anderson, 2015: 6).

What is Geography?

Geography is the study of the world with a distinctive focus on the ‘whereness’ of different phenomena. This notion of ‘whereness’ is sometimes mistaken as to mean that geographers are only concerned with where a phenomenon is found. This is not true. In fact, geographers are equally concerned with why a phenomenon is found at where it is.

To answer this question, geographers propose that ‘things, ideas, practices, and emotions all occur in a context’ (J. Anderson, 2015: 3). By ‘context’, they refer to the wide range of features that parcel up a phenomenon and influence it. Examples of these features include laws, climate and built environment. To geographers, it is the variation of contexts across space that explain why certain phenomena are only found in some places. They are interested in what produces these contexts and what effects these contexts have.

The importance context lies in how it promotes some actions while suppressing others. Consider the case of jogging in different places. It is generally free for us to jog in parks because the regulatory context we are in, i.e. the bylaws of parks, usually do not prohibit running. However, we are likely to be told off for jogging in a cinema because our act contradicts the regulatory context of a cinema, which requires people to keep quiet.

A Cultural Geography Approach

Following from above, cultural geography is the study of ‘the intersections of context and culture’ (J. Anderson, 2015: 6). A cultural geography approach brings the interest of geography about context to bear upon culture, while highlighting the importance of culture to how space is shaped.

On the one hand, cultural geographers think spatially about culture (K. Anderson et al., 2003: 6). They want to map out and explain the diversity of culture across space. They are interested in why certain kinds of food, music or clothing are only found in some parts of this world. This involves thinking about how these cultural traces are produced through the interaction of people – or more specifically their ideas – and the contexts they are in.

Mapping helps us understand cultural diversity of a place (Photo from PICRYL) / Public Domain)

On the other hand, cultural geographers also think culturally about space (K. Anderson et al., 2003: 6). They want to reveal and account for the cultural significance of particular sites and landscapes. They are interested in why certain buildings, streets and mountains are imbued with special meanings. They take culture as the context which powerfully influences the ways people think of, feel about and physically transform space at a specific location.

In short, culture literally takes place – occupying certain space and giving it distinctive appearances and identities. In other sections of this website, we shall adopt this cultural geography approach to unpack how the tapestry of Chinese culture has been woven.

References

Anderson, J. (2015). Understanding cultural geography: Places and traces (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Anderson, K., Domosh, M., Pile, S., & Thrift, N. (2002). A rough guide. In K. Anderson, M. Domosh, S. Pile, & N. Thrift (Eds.), Handbook of cultural geography. SAGE Publications.

Price, P. L. (2010). Cultural geography. In B. Warf (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of geography (pp. 634–640). SAGE Publications.

Traces constitute places

According to Anderson (2010), traces are cultural marks, residues or remnants left in place by people with different values. Sometimes, people inadvertently leave these marks behind without giving much thought to them, or indeed their ramifications on future populations. More often than not, however, people deliberately leave traces behind in the hope of promoting their values to a wider audience beyond their own cultural and temporal context.

It would not be an overstatement to say that traces make up almost any place in living existence. The physical traces in the Hong Kong Exchange Square, for example, are plain to see: a fountain, a building complex, and a collection of sculptures, among other curiosities, greet commuters and visitors on a daily basis. Most traces are material things such as buildings, signs, and graffiti, which leave discernible marks on the physical environment. Less apparent are the immaterial traces, like memories and emotions associated with events, which enable us to sense and remember places in non-tangible ways through hearing, smelling, tasting, and feeling. Despite their incorporeal nature, we can think about these kinds of traces, reflect on them, and even reminisce about them.

Traces can be durable both in a material form (e.g. a building with special design) and a non-material form (e.g. permanent marks on our memory or mind). Ultimately, all traces – material or immaterial, durable or transient – function as connections, a kind of thread that ties the meaning of places to the identity of the cultural groups that constitute them. Anderson (2010) thus argues that traces tie cultures and geographies together, influencing the identity of both.

Hong Kong Exchange Square: A place with multiple traces (Photo by WiNG / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Place as an ongoing composition of traces

A place is never dull and static, even though it may so appear. Traces, cultural marks left by groups of people with different values, constitute any place. Cultural geographers often make a distinction between material traces, like a place’s buildings, sculptures and restaurants, and non-material traces, like the associated emotions and memories of its locals. Some traces may evolve over time, which in turn changes the identities and meanings associated with the place. Other traces, by contrast, remain as relics of the past. These serve as a much-needed reminder, to locals and new arrivals alike, of the place’s history and culture.

Take Wan Chai, one of the earliest settlements in Hong Kong, as an example. It was once a notoriously old and dilapidated part of the city, yet many locals harbor fond memories of its past. Lee Tung Street, for instance, was affectionately known as the “Wedding Card Street” due to its legacy of being a center of publishing and manufacturing of wedding cards, lai see, fai chun, and other items. However, urban redevelopment since the early 2000s, driven in large part by the emergence of luxury residential developments, has transformed the district into an up-market neighborhood. The material traces are changing, with the emergence of new high rises, renovated buildings and upscale shops. While Wan Chai is establishing a new image, the fond memories of its humble beginnings still remain indelibly in the hearts of locals.

A place is not a fixed entity. Rather, as the example of Wan Chai shows, it is an endlessly dynamic one, where ever-changing traces coalesce to form new cultural ideas, activities, histories, and possible futures.

Lee Tung Street before redevelopment (Photo by Jerry Crimson Mann / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Lee Tung Street after redevelopment (Photo by Wikipedia User - Wpcpey / CC BY-SA 4.0)

All geographies are regulated

This is an important statement in cultural geography, meaning no place exists in vacuum. The following images outline the regulations imposed on a range of places. In Kowloon Park in Hong Kong, visitors are reminded that some habits are prohibited; on the Hong Kong MTR Platform, it is considered normal not to place hands on the sliding glass doors, put your belongings on the gates and rush to the yellow line; in Bangkok’s Grand Palace, you should dress properly– shoulders and knees covered for both sexes.

Prohibition signs at Kowloon Park (Photo by Pallowoom14 / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Dress code for entering the Grand Palace, Bangkok (Photo by Sodacan / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Reference

Anderson, J. (2010). Understanding cultural geography: Places and traces. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

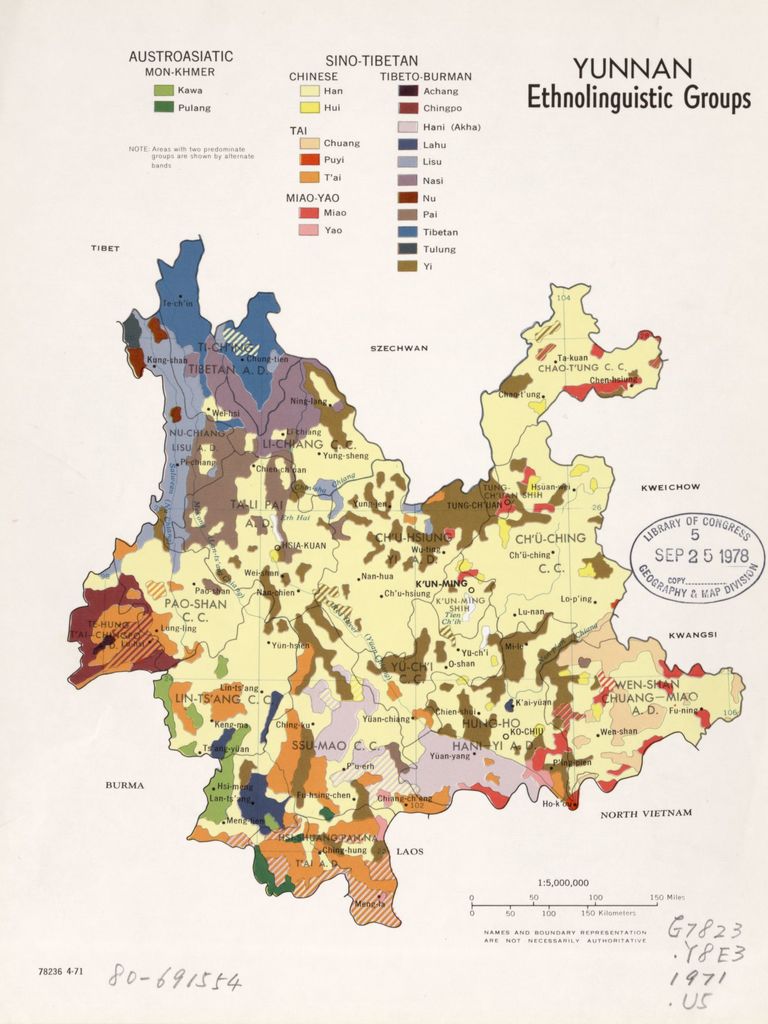

Developed over thousands of years with a changing boundary, China boasts one of the world’s most diverse culture. As the Chinese proverb goes, local variations in culture in China can be as great as having ‘different temperaments every ten li, different customs every one-hundred li’(十里不同風,百里不同俗) (Overmyer, 2001: 18). With reference to our discussion in “What is Cultural Geography?”, a cultural geography approach to China helps us better appreciate this cultural diversity in two ways.

The first way is to think spatially about Chinese culture, as this website attempts in its five Regional Topics. With a territory of around 9.6 million km2, China is marked by wide physical geographical differences. Variations in climate, landforms and locations have afforded people in different parts of the country disparate opportunities and challenges to lead their lives. Cultural diversity in China is the combined result of various unique couplings of natural environment and human experience across the country.

The second way is to think culturally about places in China, as this website attempts in its four Thematic Topics. The diversity of places that we see today in China are traces of the country’s geographically varied and historically evolving culture. A study of why each of these places have assumed their distinctive appearance and significance can generate insights into the conspicuous influence of different strands of Chinese culture in the everyday life of people in China.

Overmyer, D. L. (2001). From “feudal superstition” to “popular beliefs”: New directions in mainland Chinese studies of Chinese popular religion. Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie, 12, 103–126.