An Unusual Existence in the City

1. Introduction

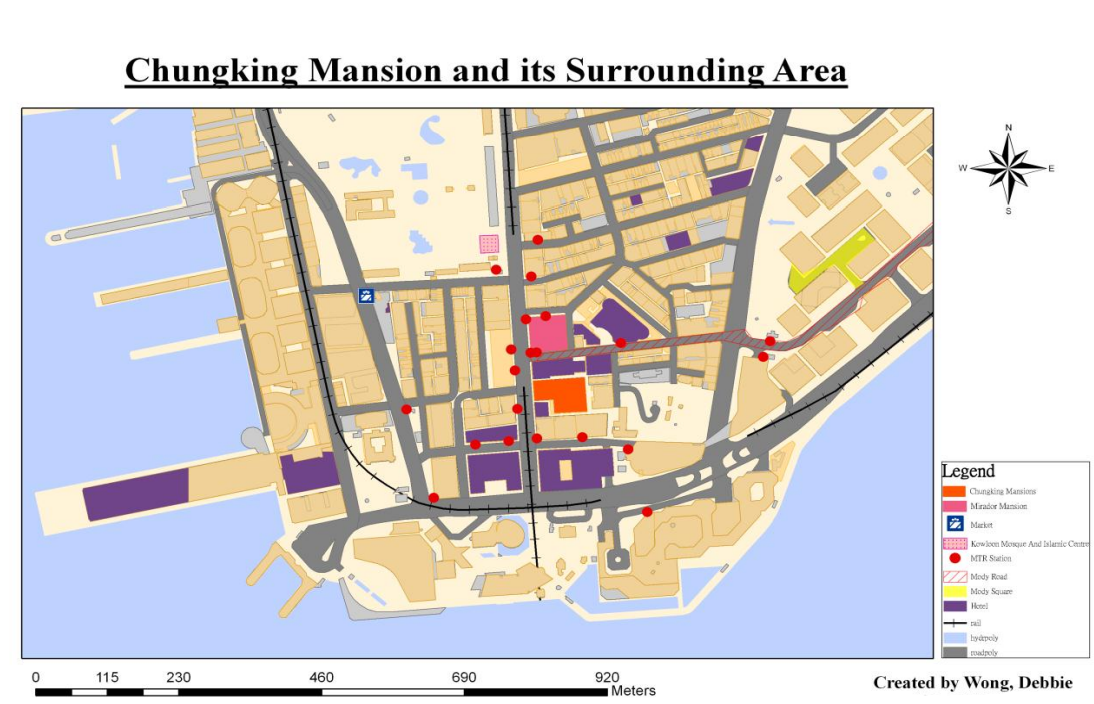

The project explores one of Hong Kong’s best recognised cultural landmarks, Chungking Mansions, in the highly accessible central business district of Tsim Sha Tsui (Figure 1). Surrounded by many luxurious hotels and high-end shops, Chungking Mansions stands out as a vertical cluster of small businesses and guesthouses, where ethnic minorities ranging across traders, workers, tourists and asylum seekers converge. This earns Chungking Mansions the name “Ghetto at the Center of the World”, after the title of Gordon Mathews’s (2011) seminal anthropological account of the building.

Chungking Mansions and its Surrounding Area

Why can we find Chungking Mansions as a “ghetto” in Tsim Sha Tsui, where land rent is sky high? How is the cultural – particularly ethnic – complexity inside the building embedded within Hong Kong’s geographical context? These are the questions this project attempts to address from a cultural geographical approach, with the aid of Henri Lefebvre’s theory of spatial triad.

Theoretical Approach: Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad

A cultural geographical approach analyses the diversity of symbolic and material practices of human communities as cultural traces – outcomes of interaction between culture and the geographical context in which these traces are found. Accordingly, this project takes Chungking Mansions as a cultural trace produced through the interactions between its many stakeholders (e.g., property owners, vendors, visitors, etc.) from diverse cultural backgrounds on one hand, and the socio-spatial context of Hong Kong evolving over time.

Proposed by French sociologist Henri Lefebvre, the theory of spatial triad offers a framework to systematically analyse how cultural traces are produced through: (i) interactions between actors with different social status over space, and (ii) interactions between these actors and the space for which they compete. As its name suggests, the theory draws attention to three analytical dimensions, “representations of space”, “representational space”, and “spatial practice”. The following table explains their meanings and their application in the subsequent analysis of Chungking Mansions.

Analysing Chungking Mansions through Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad (Source: Compiled based on McCann, 1999)

|

Dimension |

Definition |

Example |

Analytical focus in Chungking Mansions

|

|

Representations of space |

Spatial imaginations of those in power, regulating how space should be ordered and used |

Official zoning plan for a city |

Government policies and property owners’ decisions which shape the physical layout, functions, and ethnic composition of the building (Section 3.1)

|

|

Representational space |

Symbols imbued in space by people living in it, often for challenging existing representations of space

|

Artistic representation (e.g., movie) of a city |

Attitudes of different people towards the building (Section 3.3) |

|

Spatial practice |

Physical space and the everyday routines and experience of people living in it

|

Actual spatial activities in a city |

Physical features, everyday activities, and social relations in the building (Section 3.2) |

Chungking Mansions as a Complex Cultural Trace

Why has Chungking Mansions developed into an ethnic enclave?

For many outsiders of Chungking Mansions, the most observable phenomenon in the building is the gathering of people from diverse ethnic backgrounds, mostly South Asians and Africans. This is made possible by three ways Hong Kong was, or is, politically and institutionally positioned in the world (Mathews, 2011).

First, the significant presence of ethnic South Asians can be traced back to the early history of Hong Kong as a British colony, which began in 1841. Back then, the Indian Subcontinent was also under British rule. Some South Asians came to Hong Kong as recruits of the British Army and the city’s colonial government, while others as traders and labourers.

Second, people from various parts of the world are drawn to Hong Kong as an international commercial centre. Located midway between the Chinese mainland and Southeast Asia, Hong Kong has developed as a gateway for traders to multiple rapidly emerging economies. Notably, more African entrepreneurs can recently be seen in Hong Kong as they visit the city to buy Chinese products for resale in their home countries.

Third, consolidating its geographical advantage in trade development, Hong Kong champions free trade and adopts visa-free policies for many nationals to facilitate flows of goods and people. These moves attract for Hong Kong not only traders and tourists from many countries, but also attract asylum seekers and foreign illegal workers.

With these factors in mind, a more specific question comes: Why do all these people from diverse backgrounds specifically cluster in Chungking Mansions? For South Asians, this might be a matter of following the choice of their early settlers in Hong Kong, many of whom concentrated in Tsim Sha Tsui. However, more generally, this has to do with the building’s availability of affordable spaces for business and accommodation.

Trace of South Asian community in Tsim Sha Tsui: Halal meat store

Built in 1961, Chungking Mansions boasts a total of 920 co-owners (Mathews, 2011, p. 38), as it is partitioned into multiple units conveyed to different parties. Given the building’s extremely fragmented ownership, it has been difficult for individual co-owners to pool together enough ownership shares to sell the building for redevelopment. As the building deteriorates, co-owners can only lease their units a low rent. In a visit to the building in 2017, we learnt that the monthly rent of a shop selling phones and accessories is only about HKD 17,000. Such low-cost space is ideal for ethnic minority migrants, who come to Hong Kong with financial difficulties, to make a living with a small business.

How do people make a living in Chungking Mansions?

Chungking Mansions is divided into three distinct clusters of different functions. For the stores mentioned above, they are found in the building’s first two floors, each as a separate cluster. The first floor is home to stores selling SIM cards, food, clothes and other daily necessities, and several money exchange stores, while the second floor is dominated by stores selling electronic gadgets. Meanwhile, the third floor and above is the territory of guesthouses and restaurants.

Chungking Mansions as a cluster of guesthouses

Guesthouses in Chungking Mansions have been known for their affordability. They first came to significant attention in the 1970s, after being featured in the famous travelling guidebook “Lonely Planet” for accommodating backpackers at very low prices (Mathews, 2011). Since the 1980s, they have blossomed within Chungking Mansions through partitioning of apartments, meeting demand from tourists with a tight budget and traders from developing economies for low cost accommodation. This contributes further to the large number of ethnic minorities in the building.

The significance presence of ethnic minorities, however, has not resulted in elaborative display of ethnic or religious features in Chungking Mansions. This is because of two reasons. Firstly, limited floor space makes it impractical to do so. Secondly, some owners are concerned that religious items may not be welcomed by everyone and thus not beneficial to their businesses.

Indeed, the economic imperative can push even the most fundamental religious principles out of consideration. According to the Quran, alcohol is prohibited for Muslims. Surprisingly, one of the Muslim restaurants we came across was selling beer to customers. “Since we just have to make a living, Allah will understand,” the boss of the restaurant shared.

What does Chungking Mansions mean to its outsiders and insiders?

To many local Chinese, Chungking Mansions is unwelcoming and dangerous. This impression stems not only from the building’s sizeable ethnic minority population which they are unfamiliar with, but also a 1994 Hong Kong movie entitled “Chungking Express”. Directed by the renowned filmmaker Wong Kar-wai, the movie depicted Chungking Mansions as a place where only people with complicated backgrounds or gangsters would go. It has had a huge impact on the public in terms of engendering and spreading the impression of the building as a “prohibited land”.

However, to the many ethnic minorities residing or working in it, Chungking Mansions is rather their ‘beacon of hope’ (Mathews, 2011, p. 16). Popularly associated with a sense of insecurity, Chungking Mansions has faced downward pressure for the rental level of its retail units. While this is hardly pleasing to the buildings’ many co-owners, it is good news to migrants and traders from the developing world, who are finding a gap in a global capitalist system working against the interest of their countries and them. To them, given the relatively low cost of finding refuge and doing business in it, Chungking Mansions stands as the best place for them to climb up the social hierarchy through their hard work, eventually overcoming the poverty and discrimination they currently suffer.

Conclusion

This project has attempted to deploy Henri Lefebvre’s theory of spatial triad to unpack how Chungking Mansions represents a cultural trace produced through three aspects of interaction between it as a multi-storey architectural space and various actors. First, territory-wide policies and rental decisions of property co-owners promote the concentration of ethnic minorities with developing world origins in Chungking Mansions. Second, some ethnic minorities are becoming less unusual as they prioritise economic pragmatism over their religious traditions. Third, despite the previous point, personal perception among some local Chinese and cinematic representation continue to obscure Chungking Mansions’ value to support the struggle of ethnic minority individuals to achieve prosperity, thereby keeping the building behind a sense of unusualness.

References

Mathews, G. (2011). Ghetto at the centre of the world, Chungking Mansions, Hong Kong. Hong Kong, China: Hong Kong University Press.

McCann, E. J. (1999) Race, Protest, and public space: contextualizing Lefebvre in the U.S. city. Antipode, 31(2):2, p.163–163-184.