1. Introduction

This project examines the historical transformation of Kowloon Walled City from a Qing military outpost into a densely populated “ungoverned” enclave and, eventually, its clearance in 1993–94. The phenomenon deserves attention because it condenses wider tensions between state authority, capitalist urban development and everyday survival strategies of marginalized residents in a tiny piece of urban space. We treat Kowloon Walled City as a cultural trace: a material and symbolic outcome of how ambiguous sovereignty, refugee inflows and informal economies interacted over time. Geographically, the case is shaped by its liminal position between British Hong Kong and mainland China, chronic housing shortage and weak formal governance. Culturally, it is rooted in Chinese clan networks, triad organizations and a strong sense of belonging. Analytically, the project draws on cultural geographical concepts of place, sense of place, social norms, economy–culture relations and hegemony to link geographical context, culture and this urban enclave.

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

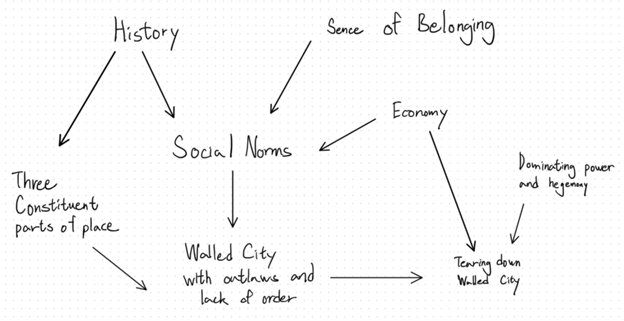

Geographical perspective states the rules, norms and physical features of a specific place, and cultural perspective states the common values and attitude of the people in the place. Cultural geographical perspective is an intersection of geographical and cultural perspective, accounting for both material and non-material traces. Hence, the perspective is to explain the formation of geographical features with cultural perspective, and vice versa.

“History forms social norms” is one concept to be discussed in the analysis, social norms refer to both the self-identity of individual, and common values, memories of the people in the place. History provides common memories to the society, and shows consequences of choices that have been made (Significance of History for the Educated Citizen | Public History Initiative), providing common values and responsibility to individuals.

“Economy and culture are closely related” is another concept to be discussed, when researching people's values in the place, historical economic data plays a huge role in explanation, evidenced by the poor economic conditions post WW1 induced Germans into valuing Nazism (Aftermath of World War I and the Rise of Nazism, 1918–1933 - United States Holocaust Memorial Museum).

The concept of “Three constituent parts of place” will be analyzed. It shows how a “space” can become a “place” by fulfilling location(the coordinate), locale(the environment both natural and historical) and sense of place(social connection to the place). The history of how the locale and sense of place is formed will be discussed in the following research.

The concept of “Sense of belonging” is hinted as a force of cultural purification, in which local cultures are accepted while foreign cultures are rejected.

The concept of “Dominating power and hegemony” is applied in the research. Dominating power can be government, foreign countries or community. New power tends to alter the place’s norms to create new values to stabilize their powers, as evidenced by Hitler turning German’s frustration from unemployment to Jews and other races (From Citizens to Outcasts, 1933–1938 - United States Holocaust Memorial Museum).

The history of Kowloon Walled City’s original military position forms the locale of the place and explains part of the social norms, in which the constituent parts of place explain how Kowloon Walled City becomes a place. Economic factors shape social norms, and sense of belonging shows resistance to change in norms. In which social norms explain how Walled City became a criminal haven.

3. Empirical Analysis

In the past, Kowloon Walled City was a densely populated, ungoverned urban area, filled with a mixture of culture and people in the area. Kowloon city was an area that is already a populated area itself. This historical place’s sovereignty is quite ambiguous with its historical treaties (Girand & Lambot, 1993), hence it creates an environment that cannot be ruled by any governing body, allowing multiple job opportunities in the grey area of the law, such as unlicensed doctors, prostitution, and even gambling (Fraser & Li, 2017). Although this seems to shine a very negative light on the area, there is another side to the city. The City’s dense population allow words to spread through the neighborhood quickly, creating a sense of order among each other in order not to be bullied by the rest of the neighbors. People in turn, created their own social law without official authorities (Sinn, 1987). If argument were to break out, situation would mostly dominated by local triads and informal networks, rather than official state power.

However, the City’s geography became a symbol of defiance. The reason for more people coming into the city and why local triad were in power is that refugees, migrants, and those seeking to escape the reach of formal law seek shelter in the Walled city due to it being an ‘ungoverned’ part of Hong Kong (Wesley-Smith, 1973). People with a degree of knowledge, skill, or capital can easily set up their business as it is still an easily accessible part of Hong Kong. Due to the convenience in location, materials can easily be transported into the area and there is also populated area outside the walled city. People with less resource then tends to join local triads in order to make a quick living (ALSuwaidi et al., 2024).

Another geographical factor of why Kowloon walled city has such diverse culture is that Hong Kong is near China. Back in the civil wars days, many Chinese people flee to Hong Kong in order to escape the war between the Nationalist party and the Communist party (Fraser & Li, 2017). However, as Hong Kong has law with refugees and officials doesn’t take in people unlimitedly, people started smuggling into Hong Kong. As smugglers are illegal immigrants, they need the shelter from Kowloon Walled City in order to stay in Hong Kong, away from the war in mainland.

The triads’ control over gambling, prostitution, and protection rackets, whereas family or clans will take up a more usual day to day aspects of the economy such as food and retailing, creating Kowloon Walled City’s own underworld culture.

As there was overcrowding and lack of infrastructure. Residents built and modified their homes with little regard for official regulations, creating a unique architectural landscape. This grassroots urbanism reflected a collective resistance to external control and a pragmatic approach to daily life, creating the culture of grassroots urbanism in an unique area of the vibrant and modern Hong Kong (Wesley-Smith, 1973).

Situated within Hong Kong but distinct from its regulated urban environment, the Walled City developed a hybrid identity. Residents navigated between Chinese traditions and the cosmopolitan influences of Hong Kong, resulting in a cultural blend that shaped local norms, values, and attitudes toward authority. This hybrid identity culture gives the residents a deeper sense of belonging to their turf and therefore they were often very strong and united against external powers trying to use their city as a place for external use.

The most obvious issue was the mess of no official control. Fraser & Li (2017) said those unofficial businesses ran wild: some people set up “clinics” without being real doctors, and houses were built however people wanted—some had three floors stacked on top of a tiny shop, with no windows or fire exits. It was a world away from Hong Kong’s clean, regulated streets, and it put people in real danger. There were also fights over power: the rules from clans and triads often clashed with the Hong Kong government’s orders. Worse, most people there were left out of Hong Kong’s basic help—they couldn’t go to public hospitals for cheap or send their kids to regular schools, which made the gap between them and other Hong Kong residents even bigger.

These problems finally made things shift. Between 1993 and 1994, the government tore down the Walled City. It was a clear sign that a “place with no rules” just couldn’t exist in a modern city—so the area started following official laws, with proper houses and shops built later. But something else changed too: people stopped seeing the Walled City as just a “bad spot.” Its jumbled, self-built houses and the way neighbors stuck together became part of Hong Kong’s history. That mix of Chinese traditions and Hong Kong culture even showed how diverse Hong Kong really was. It also made people think differently about managing cities—clans and triads had kept a crowded community from falling apart, which made officials realize that local groups could help too. Later, when building new neighborhoods, some officials asked residents to join in planning—something they might not have thought of without the Walled City’s example.

4. Conclusion

This project shows that Kowloon Walled City was a cultural trace of the interaction between a liminal geopolitical position, refugee-driven urban pressure and Chinese cultural institutions such as clans and triads. Using a cultural geographical perspective on place, sense of place, social norms and hegemony allows us to link its extreme built form and informal economy to deeper histories of ambiguous sovereignty, housing scarcity and grassroots self-governance. The concepts of “history forms social norms” and “economy–culture relations” are particularly useful for explaining why the City became both a criminal haven and a tightly knit community. However, they need to be complemented by attention to state power and demolition policies to capture later transformations. Our findings suggest that contemporary urban policy should recognize local networks as potential partners in governance while avoiding the neglect and exclusion that produced such extreme environments in the first place.

References

Aftermath of World War I and the Rise of Nazism, 1918–1933 - United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (n.d.). https://www.ushmm.org/learn/holocaust/aftermath-of-world-war-i-and-the-rise-of-nazism-1918-1933

From Citizens to Outcasts, 1933–1938 - United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (n.d.). https://www.ushmm.org/learn/holocaust/from-citizens-to-outcasts-1933-1938

Fraser, A. & Li, M. (2017). Underworld and Order: The Social Ecology of Kowloon Walled City. Hong Kong University Press. https://www.hkupress.org/

Girand, P. & Lambot, J. (1993). Sovereignty Ambiguity in Historical Treaties: The Case of Kowloon Walled City. Journal of Hong Kong Studies, 8(2), 45-62. https://www.jhks.hku.hk/

Significance of History for the Educated Citizen | Public History Initiative. (n.d.). Public History Initiative. https://phi.history.ucla.edu/nchs/preface/significance-history-educated-citizen/

Sinn, E. (1987). Informal Governance in Unregulated Zones: Clans and Triads in Kowloon Walled City. Modern China, 13(3), 321-340. https://journals.sagepub.com/home/mcx

Wesley-Smith, P. (1973). Refugees and the "Ungoverned Zone": Kowloon Walled City 1949-1970. Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, 5(4), 38-45.http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/serial?id=bcas