1. Introduction

The climate and geographical traits vary greatly across different cities in China. With these characteristics influencing the cities’ culture, this project examines how the geographical factors of Zigong City have shaped its unique food and tourism culture. Salt pans, salt warehouses, and workers' settlements are traces behind the history and culture. They recorded how the local environment and salt economy shaped people’s daily life, spatial layout and even collective rituals. From the trace, we can tell the past modes of production, social hierarchy and communication identity through today's landscapes and practices.

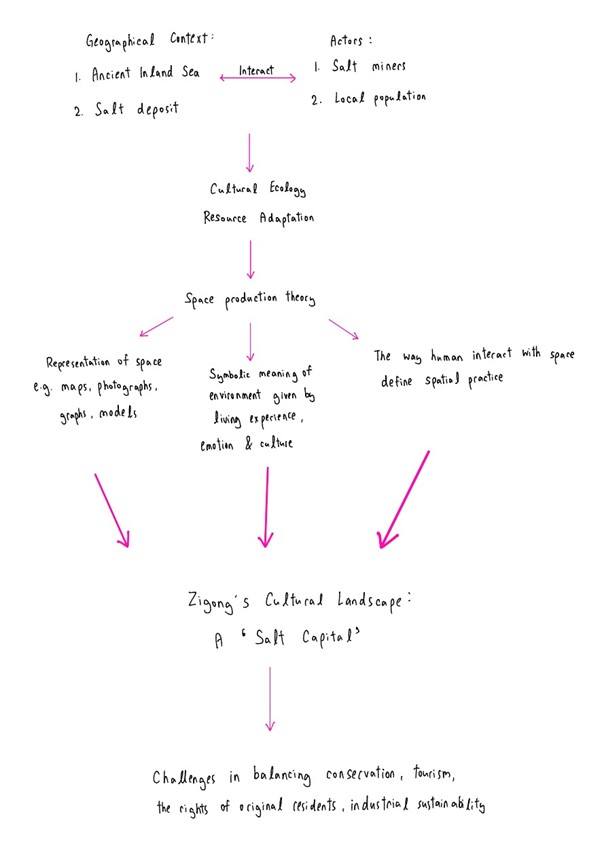

The spatial location of the Zigong City is favourable for the production of salt, hence giving rise to the prosperous economy of ancient Zigong City and its special food culture. The project primarily draws upon Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space, specifically the triad of spatial practice, representations of space and representational spaces. Also, Julian Steward’s cultural ecology is used to analyse, from a cultural geographical perspective, how Zigong’s unique geographical context and culture are interlinked and mutually produced.

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

A cultural geographical perspective focuses on how culture is constructed, practised and represented in space and place. It emphasises that landscapes are not simply natural or neutral backdrops, but are shaped by power relations, economic structures, social practices and cultural values. In this view, the built environment, everyday spaces, and even “ordinary” scenery all become cultural texts that can be read and interpreted, revealing how a society’s history, identities and power dynamics are embedded in the material landscape.

Our project seeks to link the cultural geography of Zigong City to the space production theory constructed by Henri Lefebvre. In space production theory, there are three main ideas. Representations of space are defined as the various ways humans conceptualize, visualize and describe space, ranging from concrete forms like maps and photographs to abstract forms like graphs, models and textual descriptions. The second idea, representational space is defined as the symbolic meaning a person or group gives to a physical environment through living experience, emotion and culture. The last one, spatial practice is defined as the way humans interact with, organize and give meaning to physical space through their daily activities, routines and social actions ( Schmid, C, 2022).

We will also use the theory of anthropology—cultural ecology, which was suggested by Julian Steward in the 1950s, headlining the significance of environmental factors in shaping cultural features. (Cultural Ecology | Research Starters | EBSCO Research, n.d.) Zigong has adapted to the natural environment, utilizing her special geography to become "Millennium Salt City". This further shaped her distinctive food culture and developed tourism.

3. Empirical Analysis

Zigong City is located in the Southern part of Sichuan Province, China. Its name comes from two major salt-production sites in the city, Ziliujing and Gongjin, showing the importance of salt to the Zigong City. The Sichuan Basin was once an ancient inland sea; it held concentrated brine and saline rock deep beneath its surface, mining salts here for centuries (Cavish, 2025). Zigong City is also characterized by hills and low mountains that contain brine-rich aquifers fed by rock salt. It makes Zigong City an ideal location for sale extraction.

The influence of Zigong's salt heritage is prominent in the culinary landscape of the city, featuring salt in flavour of traditional Sichuan food. Since salt was easily available in the past, it influenced not only food flavourings, but also food preservation, which led to base flavour created in cooking methods that were bold or savoury. One notable example of a salt heritage dish is salted beef slices-thinly sliced beef coated in salt and soy sauce, dried and smoked at a low temperature. This example of cooking traditions originates from a preservation method stemming from Zigong's salt trade.

Besides, the salt sector is a substantial focus of cultural tourism. This is partly due to heritage sites, including the old salt wells and artifacts associated with traditional methods of drilling. They comprise visitors who are interested in history and industrial culture, which falls beneath cultural tourism, and with them comes an increase in visitors coming to heritage sites, along with all the meanings associated with culture. Festivals like the incredibly well-known Lantern Festival, which have origins in the salt worker's settlement communities, add to cultural tourism, drawing visitors for an immersive experience while celebrating land, culture, and the economy of salt. (陈密容, n.d.)

There are several actors that have played an important role in bridging the gap between the phenomenon and the geographical context through specific mechanisms. To begin with, the workers in the salt industry have perfected the salt-drilling techniques. For instance, the Shenhai well was drilled to extract salt from concentrated brine. This greatly encouraged the extraction of salt from the natural brine and saline rock and allowed locals to make good use of the resources in the environment to make profits. Besides, the local population has also been crucial in bringing the geographical context of Zigong city and the culture together. With the rich supply and thus easy accessibility of salt, they have been able to create unique usage of it. Apart from inventing the salted beef dish, which then evolved into an iconic local cuisine, locals also developed the usage of salt as a preservative. Though seemed as taken for granted in the local’s eyes, the ancient salt extraction method and homely food have become attractive tourists’ must-try. The tourism of Zigong city is thus boosted. From this, it can be seen that the salt farmers and the local population have forced interaction between the culture and the geographical context of Zigong city.

The cultural landscape of Gongshi as a “salt capital” reflects a series of emerging challenges and ongoing transformations. With industrialization and market liberalization, large-scale mechanized salt production and cheap imported salt have undercut the cost advantage of traditional sun-dried salt. Local salt making is no longer a routine economic activity but has gradually become a “past” industry (Chan, 2018). This decline itself is a cultural trace: we can see abandoned salt pans and repurposed salt warehouses in the landscape, marking the shift of salt from a productive resource to a historical memory.

In response to these structural changes, the government and business sector have repositioned “salt” as a cultural resource, using it for city branding and tourism promotion—for example, salt museums, salt spa experiences, and salt-themed souvenirs (Li, 2020). The identity of “salt capital” is repackaged to tell local stories and attract tourists and investment. This “heritage + branding” strategy on the one hand extends the symbolic meaning of salt, allowing the public to continue to know Gongshi through its landscape and cuisine; but on the other hand, it introduces commercial tensions.

Tourism development may drive up land prices and push original residents and salt-worker communities to relocate, excluding those who actually laboured in the salt industry from the new “salt capital” narrative (Smith, 2006). At the same time, many souvenirs marketed as “Gongshi salt” are in fact produced elsewhere, creating “fake locality” and weakening the authentic link with local production. Moreover, the harsh, time-consuming work of salt making is often repackaged into a brief recreational experience, aestheticizing historical labour as light entertainment. Visitors mainly engage with the surface landscape while overlooking the deeper social relations and class dimensions behind it. Thus, the cultural trace of Gongshi as a “salt capital” simultaneously records economic restructuring and exposes ethical and social justice issues arising from the commodification of culture and city branding. How to balance conservation, tourism, the rights of original residents, and industrial sustainability has become the central challenge revealed by this landscape.

4. Conclusion

The space production theory and the anthropology-cultural ecology closely relate to the salt industry of Zigong city. While the former describes the local’s adaptation to the environmental advantages of the city, the latter theory points out that the locals’ utilization of natural spaces have granted them unique values.

To combat gentrification and the displacement of the original saltworking community, the government could create a Resident Retention Fund which would allocate 20–30% of all tourism sales to subsidize housing and provide relocation compensation only in the historic salt districts to maintain these residents in-place. Also, tourism operators could be mandated to include mandatory guided modules addressing labor history and class relations, replacing optional “salts raking photo opportunities” with critical education to expose the actual social relations behind the landscape rather than superficial entertainment.

References

Chan, K. W. (2018). Globalization and the transformation of traditional salt-making industries in coastal China. Journal of Coastal Cultural Studies, 5(2), 45–62.

Cultural ecology | Research Starters | EBSCO Research. (n.d.). EBSCO. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/environmental-sciences/cultural-ecology

Li, Y. (2020). From production space to heritage space: Rebranding industrial landscapes in China’s small cities. Urban Cultural Geography, 12(1), 77–95.

陈密容. (n.d.). Traditional salt-making method reflects Sichuan artisans’ wisdom- CHINESE SOCIAL SCIENCES NET. http://english.cssn.cn/skw_culture/201706/t20170628_5653736.shtml

Schmid, C. (2022). Henri Lefebvre and the theory of the production of space (Z. Murphy King, Tran.). Verso.

Smith, L. (2006). Uses of heritage. Routledge.

St Cavish, C. (2025, April 8). How salt became the white gold of Sichuan’s Zigong city and helped shape a cuisine. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/postmag/culture/article/3305202/how-salt-became-white-gold-sichuans-zigong-city-and-helped-shape-cuisine?module=perpetual_scroll_0&pgtype=article