1. Introduction

This project examines the

interaction between the theming of place in Dali Old Town and the ethnic identity

of the Bai people. Through tourism-oriented renovations, its themed landscapes

(such as restored Bai architecture, folk performances, and cultural products)

are reshaping the local space and ethnic identity, leaving tangible cultural

traces(the shift of traditional

customs from ‘daily practice’ to ‘tourist spectacle’). These traces record both the long-standing

integration of modern and Bai cultures and the contemporary negotiation between

tourism capital and local traditions (1,2). This phenomenon warrants close

attention, as it represents a powerful global process: local cultures are being

repackaged into marketable landscapes, fundamentally reshaping ethnic

identities. Geographically, Dali’s location as a pivot on the Sino-Tibetan

route, its tourism-dependent economy, and Yunnan’s “14th Five-Year” cultural

tourism policies drive this theming. The project draws on Urry’s “tourist gaze”

and Relph’s “place identity” concept to analyze the interconnections between

the phenomenon, geographical context, and culture.

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

In this work, we adopt a cultural geographical approach

to decipher the way theming of place in Dali Old Town changes the Bai ethnic

identity with the help of tourism development. The cultural geography

perspective emphasizes that landscapes are not only physical but are the

results of meanings, performances, and power.. The perspective explains why the

"Bai cultural landscape" of Dali is not just handed down but is also

reconstructed.

The

idea of place-making will be introduced, as the old town has been intentionally

turned into a visible "Bai space" by the means of the restored

architecture, the streets, and the staged cultural activities so that the image

of Bai that is mostly given to the tourists is the one that has been actively

produced but not preserved. This points to cultural commodification to which

the traditional practices like tie-dyeing, Jiama painting, clay sculpture, and

even wedding rituals are converted into commercial products. Bai cultural

symbols are turning to be the major economic resources, thus causing the

discord of authenticity and tourist expectations, as pointed out by Yang, Xue,

and Song (2021). Urry’s concept of the tourist gaze clarifies these changes, tourists

come with the preconceptions of what a minority culture is, and both the

government and tourism businesses reshape the place to meet these expectations.

This mechanism is the reason why customs are being simplified into short,

visually appealing shows and traditional courtyard houses become boutique

houses.

Moreover,

Relph’s point of view about place identity being a factor in understanding the

employment of Bai symbols in the public space, either in architecture or

performances, constructing a collective feeling of “Bai-ness” that impacts not

only the tourists but also the local residents who have to figure out their

cultural belonging in a themed environment which reflects commercial logic more

and more. A recent research conducted by Bai and Weng (2023) also reveals that

tourism-driven commodification is not only reordering local cultural layers but

also pushing the visually attractive elements to everyday practices, which is

similar to what is happening in Dali. Those combined give an analytical

framework where Dali Old Town is the result of the interaction of government

policies, tourism capital, and preferences, turning the town into a cultural

trace that indicates both the persistence of Bai identity and the pressures of

commercialization, thus having a direct impact on the changes talked about in

the empirical section.

3. Empirical Analysis

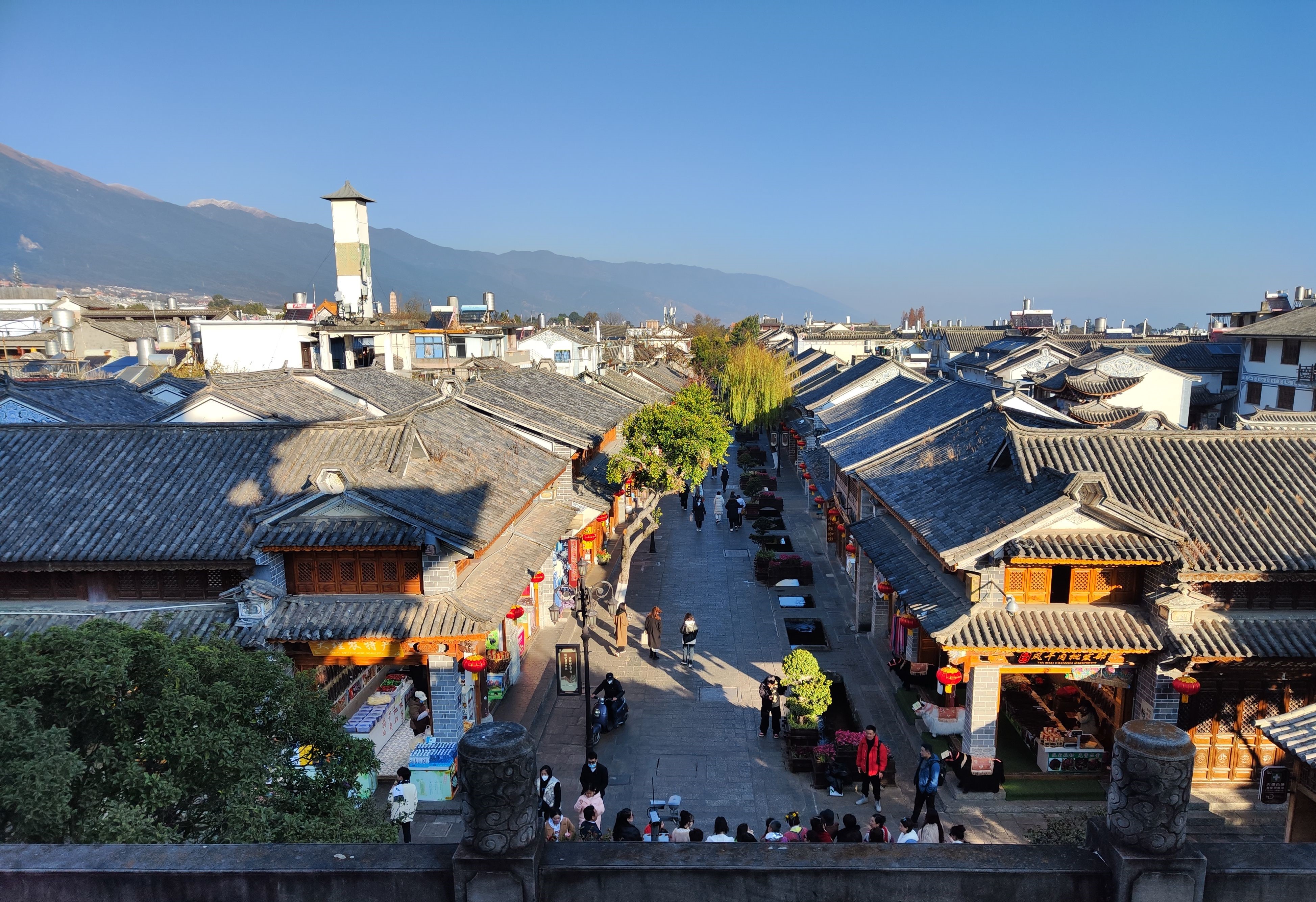

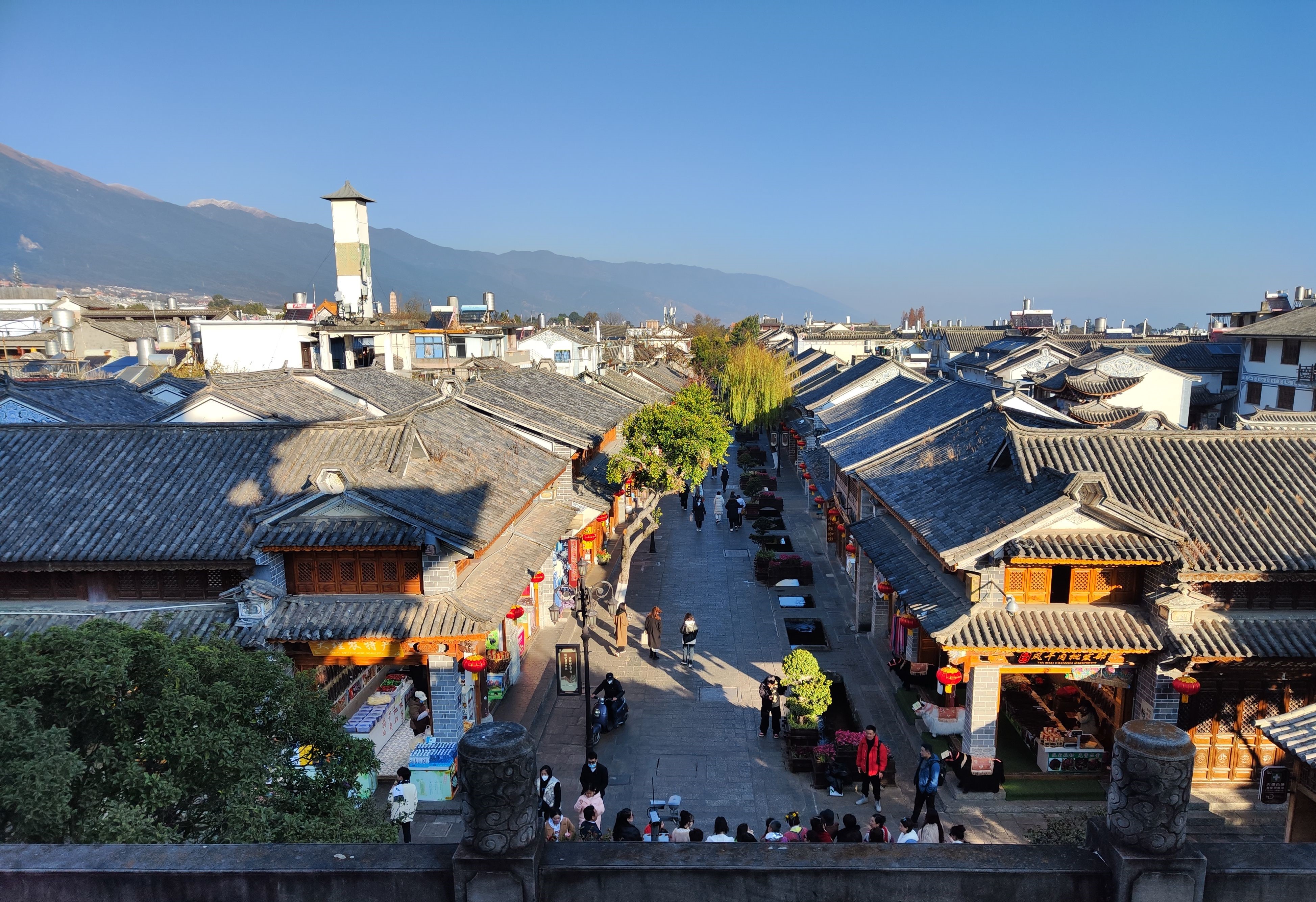

The

geographical diversity of Dali Ancient City allows four core

elements—mountains, lakes, plains (basins), and the ancient city itself—to

converge within a compact area. Centered on the ancient city, three distinctly

different terrains can be witnessed within a ten-kilometer radius: mountain

ranges, lakes, and plains (basins). The geographical diversity of Dali Ancient

City concentrates four core elements within a compact area: mountains, lakes,

plains (basins), and the ancient city itself. Dali's unique geographical

environment is inextricably linked to Bai culture. For instance, the

preservation of intangible cultural heritage, including tie-dyeing, resist

dyeing, and clay sculpture techniques—relies on the indigo plants cultivated in

the plains and basins; meanwhile, clay sculptures utilize local soil sourced

from lakeshores (4). Combined with its unique cultural background, it provides

an ideal venue for showcasing Bai ethnic culture through tourism. The Dali Old

Town as a historical and cultural tourism destination provides a tangible space

for showcasing and monetizing Bai ethnic culture, fulfilling the practical

needs of cultural preservation. (4) The local culture is selected and

rearranged, and traditional cultural elements are simplified, condensed, and

dramatized to meet market demands (tourists' time, aesthetics, and curiosity),

thus reshaping the ways in which culture is represented. In order to facilitate

economic development, the government is dedicated to developing Dali Old Town

into a renowned tourist attraction which is rich in history and culture. The

government has provided a new platform and impetus for the inheritance of Bai

ethnic intangible cultural heritage such as tie-dying, Jiama, and clay

sculpture (2023). By the combination of intangible cultural heritage and

tourism, these traditional crafts are no longer only exhibiting in museums, but

have been transformed into cultural and tourism products that can be

experienced and purchased by customers as well as have competitiveness in the

market (2024). Under the development of tourism, the Bai ethnic group can

understand the value of their own culture. Therefore, it can enhance their

sense of pride in culture and sense of identity. As a result, integrating the

Bai ethnic culture into tourism promotion can increase their cultural influence

(2024). On the other hand, driven by commercial interests, some traditional

cultural elements are simplified and repackaged to cater to tourists’

preferences. One of the examples is the performance of traditional weddings and

festival celebrations for the culture of the Bai ethnic group (2017).

Originally, the traditional Bai wedding is a complicated social ritual

involving the marriage of two families, strict procedures, specific songs, and

symbolic gestures such as “pinching the bride” as a blessing (2017). This is an

introverted and culturally significant event. However, in order to cater

tourists’ curiosity, these weddings have been adapted into daily scheduled

stage performances. The duration has been condensed to 15-30 minutes and

performances only retain the most visual elements such as gorgeous clothes, and

lively song and dance while removing all introspective aspects involving

genuine emotions and community networks (2017). Tourists become

"spectators," and the ceremony transforms from a social institution

into a cultural show, almost completely losing its original social function and

sanctity. As a result, some cultures of the Bai ethnic group are largely

presented to support the tourism industry. Local people do not feel proud of

their culture. Instead, they unhealthily display their characteristics in

pursuit of commercial gain.

4. Conclusion

“Eight Vertical

and Eight Horizontal” High-Speed Rail development in 2016 provide an accessible

route for tourism in Yunnan province. The completion of the Shanghai-Kunming

and the Nanning–Kunming high-speed railway in December 2016, slashed travel

time from Kunming to Dali from over six hours to roughly two, instantly

transforming Dali Old Town from a relatively secluded Bai cultural enclave into

one of China’s most accessible mass-tourism destinations.

The overtourism of Dali Old Town stems from the integration of its unique

geographical landscape with Bai ethnic culture: the enclosed terrain not only

fosters the romantic Bai culture but also provides a natural stage for cultural

display. Through long-term place-making, tie-dying, Jiama, and clay sculpture

and other elements, this town has been endowed with a strong sense of belonging

and identity. Since the 1990s, however, under heritage conservation policies,

development of high-speed railway, and the drive of globalized consumption,

Dali old town has undergone rapid modification. The government and capital,

responding to the “tourist gaze,” selectively simplify and stage otherwise

complex local culture: traditional courtyards are converted into boutique

guesthouses, weddings become paid performances, and historic compounds have

been commercialized. In 2025, Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture received over 5.21

million tourist visits. (Yunnan Provincial People's Government, 2025) Thus, the

old town now exhibits a double-edged sword: on the surface, a romantic Bai

ancient town; in reality, a highly themed consumption space co-scripted by

government, capital, and tourists. It is both a site of resilient Bai cultural

survival and a microcosm of the tensions in China’s ethnic minority regions

amid modernization—between tradition and commodity, authenticity and

performance, local and global—revealing the profound contradiction between

cultural heritage preservation and tourism development.

References

Bai, L., & Weng, S. (2023). New perspective of cultural sustainability:

Exploring tourism commodification and cultural layers. Sustainability,

15(13), 9880. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15139880

Chen, S. Y. (2017). A Summary of

Japanese Scholars’ Research on Yunnan Minority Cultural Studies in the 21st

Century. 现代人类学, 5(3): 33-39. https://doi.org/10.12677/ma.2017.53005

Yang, H.,

Xue, M., & Song, H. (2021). Between authenticity and commodification:

Valorization of ethnic Bai language and culture in China. International

Journal of English Linguistics, 12(5), 74–84.

https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v12n5p74

Yunnan Provincial People's Government.(2025). 大理州接待游客逾521万人次. Retrieved

November 19, 2025, from https://www.yn.gov.cn/ywdt/zsdt/202510/t20251010_318537.html

丁怡全, &严勇.

(2024). 瞭望 | 大理:文旅产业圈圈突破. 新华网. http://www.xinhuanet.com/ci/20241112/e7894c6e37d54981aac971d8f919fc6d/c.html

大理日报新闻网.

(2023). 国家历史文化名城—大理. https://www.dalidaily.com/content/2023-03/20/content_44948.html