1. Introduction

Tai O is located on the northwest coast of Lantau Island, at the mouth of the Pearl River. A natural bay provides a protective barrier for the local ecosystem. The intertidal wetlands and abundant marine resources have nurtured unique stilt houses, water village imagery, and the cultural brand of "the Venice of the East" (Tai O Fishing Village, n.d.).

Figure

1: Map of Tai O (Sources: Google map)

Best known as one of the existing fishing villages in Hong Kong, Tai O’s history can be traced back to 800 years ago. It was the home of the Tanka people, one of the earliest groups to emigrate to Hong Kong. The population was around 10,000 in the early 20th century. Yet, the number has been dropping since then (Mak, 2011).

Figure 2: 1930s Tai O (Source: Gwulo)

Figure 3: 1981 Drying shrimps (Source: Andrew Suddaby)

The

residents earned for a living by mostly fishing and salt farming, others worked

in the fields of agriculture and trading (Kwan & Tam, 2021).

Figure 4: 1981 Stilt warehouses (Source: Andrew Suddaby)

Figure 5: 1978 Fishing craft at anchor (Source: gordonvr)

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

Research Question

How does tourism development and power affect the

spatial triad and shape Tai O’s cultural landscape from a fishing village to a

tourist hotspot?

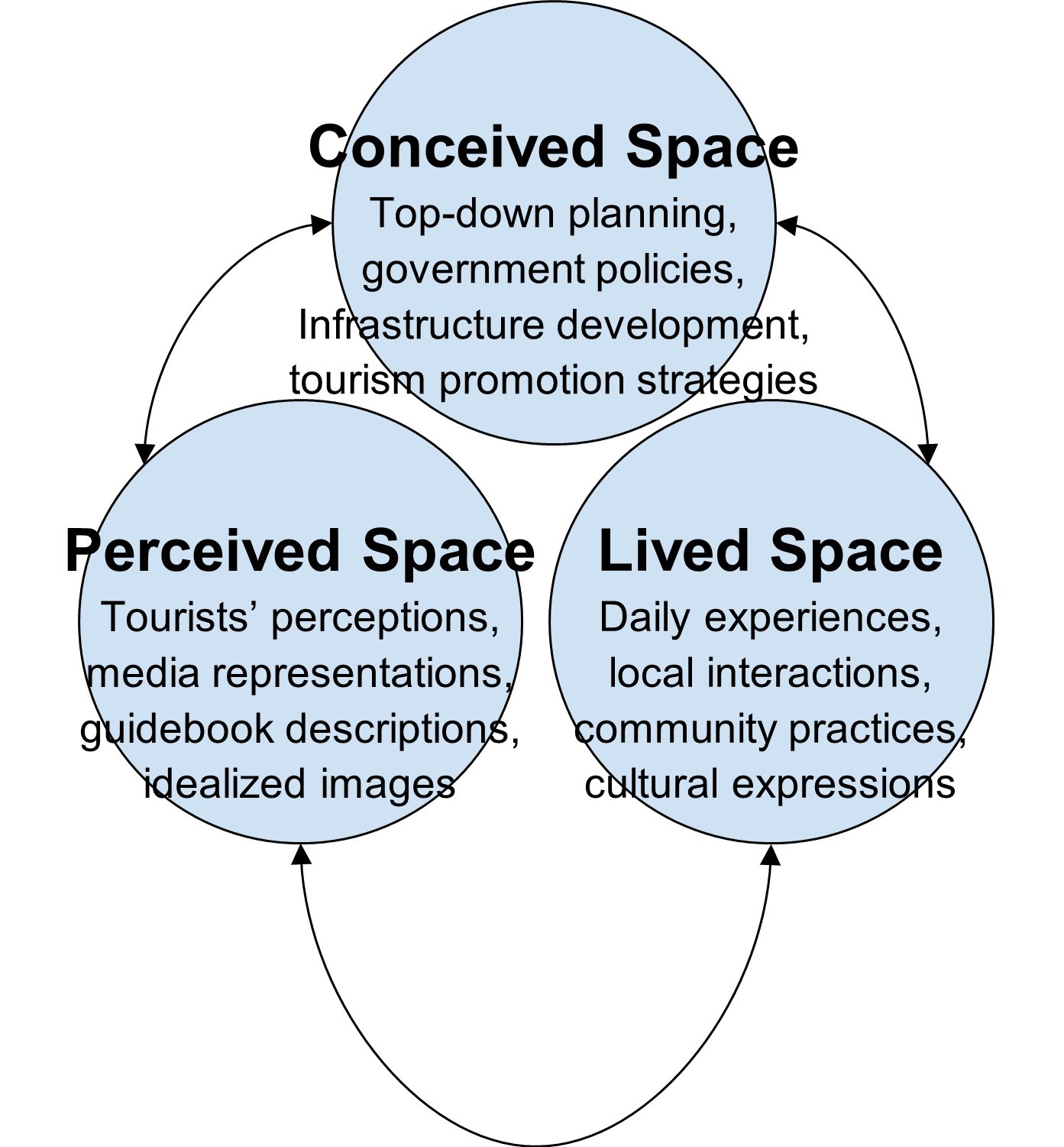

Figure 6: Conceptual framework

In this

study, Henri Lefebvre’s spatial triad is employed to analyze how tourism

development transforms Tai O’s cultural landscape from a functional fishing

village to a commodified tourist site. The triad includes: conceived space

which covers top-down planning and tourism strategies, perceived space that

includes tourists’ perceptions and media image, and lived space which focuses

on local interactions and cultural expressions(Lefebvre, 1991). The arrows show

how these 3 aspects affect each other .

In Foucault‘s power, everyone has the capacity to act, the power is not repressive, instead it is productive. Power is the relationship between people when they act on the actions of others (Lynch, 2011). The power structure is absent in society. But for the Political economy theory, power is a tool for ruling the state, and also a means of violence and coercion by the ruling class to carry out exploitation and oppression. In this project, we are combining both theories:

Within the power structure, individuals also seek to consolidate their own power simultaneously.

This is to explain the power struggle between the government and tourism agencies on the one hand and Tai O residents on the other hand in the process of turning Tai O from a fishing village to a tourist spot.

Another approach is the Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad. We are using the concepts of spaces to show how they influence one another, and most importantly, they explain why Tai O is not merely a fishing village or a tourist spot, but a socially produced space (Lefebvre, 1991).

3. Empirical Analysis

Conceived Space: How did the government turn Tai O to a tourist spot?

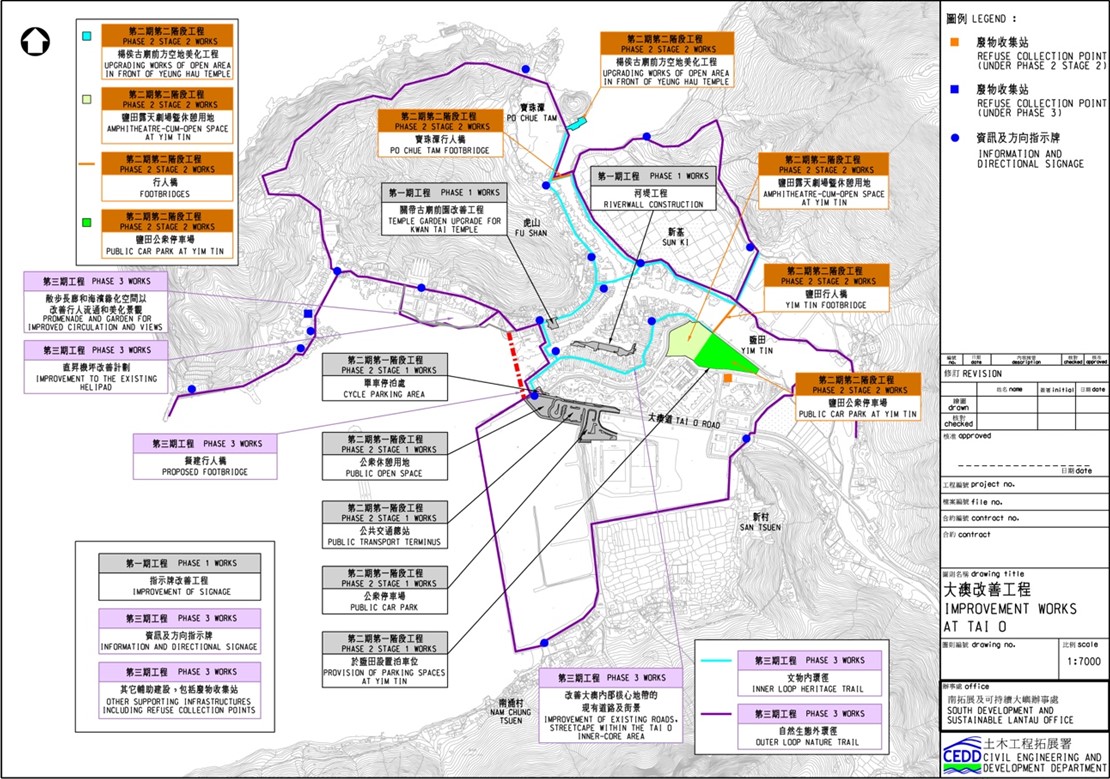

Turning Tai O from a fishing village to a tourist spot, the government implemented some projects, with the primary aim of alleviating traffic congestion and enhancing tourism capacity. These plannings of the use of Tai O’s space are categorized as the conceived space in the spatial triad, in which power is primarily exercised through top-level government planning and brand narratives of “Venice of the East” by tourism agencies. One consideration is that this power dynamic manifests where the government and large tourism stakeholders dominate resource allocation and spatial transformation, while local residents passively accept policy outcomes (South Development and Sustainable Lantau Office - Improvement Works at Tai O, n.d.).

Figure 7 : Improvement Works at Tai O – Project Scope (Source: Civil engineering and Development Department)

To begin with, it is vital to understand the role of the government throughout the transformation of Tai O. Research indicated that the government exercised absolute power over the definition and allocation of spatial resources by designating conservation areas and implementing the “Tai O Improvements Project” in phases, including bridge construction, transportation improvements (South Development and Sustainable Lantus Office, n.d.). While this aims to protect cultural and natural heritage, it also fundamentally restricts residents’ autonomy in land use and reinforces the dominant position of national administrative agencies in the allocation of spatial resources (Du Cros & Lee, 2007).

Figure 8: Artist Impression – Proposed Footbridge at Yim Tin

(Source: Civil engineering and Development Department)

Secondly, how does this dominant power shape the conceived space of “Venice of the East” (Leung et al, 2021)? From our observation, the more productive power is reflected in the branding of “Venice of the East”. The government and tourism-organizations have redefined Tai O from a functional fishing village into a tourist attraction, offering exotic experiences for consumption. This government wields decision-making authority (top-down), which produces a new spatial reality and tourist expectations, laying the foundation for subsequent commercialization and the spatial practices in living space. For example, they have proposed the phased implementation of the “Tai O Improvement Works”, including elements like bridge construction, traffic enhancements, and additional parking facilities, to meet the demands of increased visitor traffic.

This conceived space from the top level profoundly reshapes the daily practices (lived space) and perceptions of residents and tourists (perceived space) in Tai O, thus entering our next analytical dimension—lived space.

Lived Space: What tensions arise for Tai O residents as tourism transforms both livelihoods and cultural heritage?

In Lefebvre’s spatial triad, lived space constitutes the experiential and symbolic dimension where inhabitants imbue the environment with personal and collective meanings, often resisting dominant conceptions through imaginative overlays and embodied practices (Lefebvre, 1991). In Tai O, this manifests as a palimpsest of traces—layered inscriptions of Tanka heritage and adaptive identities—that emerge dialectically amid the village’s transformation from a fishing enclave to a tourist site. For instance, residents imbue spaces like stilt houses with nostalgic traces of nomadic livelihoods, linking daily rhythms to ancestral adaptability (Kwan & Tam, 2021). Temples of Guan Yu and Tin Hau, traditional festivals like dragon boat races are not only tourist attractions but also spiritual value to the residents which carries community unity and maritime worldview, maintaining oral history and traditional rituals (Ma, 2015).

Figure 9: Tai O San Tsuen Tin Hau Temple (Source: Home Affairs Department)

However, when these elements are incorporated into tourism promotion by the government to maintain attractiveness, it objectively contributes to the preservation of cultural heritage, but its intrinsic meaning faces the risk of being hollowed out. For example, privately owned stilt houses are converted into guesthouses, residents’ privacy and daily rhythms (lived space) are forced to give way to the gaze and experience of tourists (perceived space of tourists). Another example is the symbolic meaning of the Sun Ki Bridge, a profound imprint of community agency, which is also facing challenges with tourism. This bridge was built with funds raised by residents using traditional “Kun Dian” wooden pillars, which carries the collective memory of solidarity and symbolizes resistance against bureaucratic neglect (Wan & Chan, 2017). However, its primary function has now shifted to serving tourists, diluting its former symbolic meaning as a source of community pride. This transformation has introduced noise and pollution to Tai O, and created a complex emotional dissonance among residents. The autonomy of residents and their living space are being eroded by tourist spaces which led to residents’ emotional dissonance and discomfort.

Although some residents express opposing reactions, there is pragmatic acceptance of changes like stilt house repurposing for homestays, which disrupts privacy but sustains livelihoods, highlighting affective dissonances in lived space (Wan & Chan, 2013). Therefore, we would like to say that Tai O’s “lived space” is like a rewritten book, covered with the new strokes of tourism commercialization, while stubbornly preserving and constantly reproducing the ancient inscriptions of ethnic identity and community memory, forming a dynamic and tense field of resistance.

Perceived Space: How do locals and tourists differently construct meaning and attachment to Tai O’s space?

The blueprint for “conceived space” inevitably reshapes the “perceived space” of residents and tourists - their daily activities and economic practices (Lefebvre, 1991).

In responding to tourism demands, residents’ traditional livelihood strategies have undergone profound transformations: backyard shrimp paste marketing has become street performances, and fishing skills have been packaged as paid experiences (Elkin et al., 2021). This confirms the productive nature of power, it produces new behavioral patterns and economic relations by connecting modern identities to traditional fishing economies (Ma, 2015).

Figure 10: Residents teaching how to make fishing net (Source: Tai O Travel eFun)

Also, tourism yields economic revitalization, such as income from boat tours and dried seafood markets. It poses environmental threats like waterway pollution from increased boat traffic and waste, eroding ecological traces tied to traditional practices. However, this is not a one-way domination. Under the challenges, the residents demonstrate the agency emphasized by Foucault, actively transforming their life skills and cultural knowledge into economic capital. This provides a chance to fight for their livelihood and voice within this power structure, demonstrating the dialectical nature of power dynamics and the idea that individuals have their own power rather than remaining passive (Lynch, 2011).

For the tourists, before the intervention of power, tourists’ perception of Tai O remained superficial-static images of stilt houses and fishing boats captured on cameras due to the relatively closed cultural environment of Tai O. After the power dynamic reshapes the sensory experience in Lefebvre’s spatial triad, tourists shift from purely visual consumption to multi-sensory engagement (Ma, 2015). For instance, the tactile act of making shrimp patties over charcoal evokes the sense of smell while the kinesthetic learning of weaving fishing nets enables visitors to physically enter the fishing village waterways which were previously accessible only from afar, and to experience Tai O from the perspective of the locals while on a swaying boat.

All these new commercial

interactions create entirely new ways of perceiving place. This transforms

still photography into dynamic, immersive experiences, enhancing their

imagination and understanding of “life on the water”. This process raises

emotional resonance, cultural identity, and even an attachment to memories.

Through the analysis of the Lefebvre’s triad, this study shows that conceived space drives branding and infrastructure; perceived space adapts routines for economic survival; lived space resists via symbolic heritage. This interplay writes the complex narrative of Tai O’s transformation from a fishing village to a tourist attraction, yields benefits like preservation but tensions in identity and sustainability. Future policies should enhance community participation for equitable transformation.

References

Du Cros, H., & Lee, Y. S. F.

(2007). Heritage tourism and community participation: A case study of Tai O,

Hong Kong. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 2(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.2167/jht031.0

Elkin, D. K., Leung, C. Y., Wang, X., & Wernli, M.

(2021, May 7). Data Commoning in Tai O Village: History, the urban

periphery, and technology in spatial agency practice. PolyU Scholars Hub. https://research.polyu.edu.hk/en/publications/data-commoning-in-tai-o-village-history-the-urban-periphery-and-t/

Google. (n.d.). Google Map of Tai O.(2025, November 23) https://maps.app.goo.gl/7xtotzSZXgC4u7kZ9?g_st=ipc

Gwulo. (n.d.). 1930s Tai O [Photograph]. https://gwulo.com/media/19451

Gwulo. (n.d.). Drying shrimps [Photograph]. https://gwulo.com/media/22566

Gwulo. (n.d.). Fishing craft at anchor, Tai O, 1978 [Photograph]. https://gwulo.com/media/30261

Gwulo. (n.d.).Stilt warehouses [Photograph]. https://gwulo.com/media/22560

Hong Kong fun in 18 districts - Tai O San Tsuen Tin Hau Temple. (n.d.). [Photograph]. https://www.gohk.gov.hk/en/spots/spot_detail.php?spot=Tai+O+San+Tsuen+Tin+Hau+Temple

Kwan, C., & Tam, H. C. (2021). Ageing in place in disaster prone rural coastal communities: a case study of Tai O Village in Hong Kong. Sustainability, 13(9), 4618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094618

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.). Blackwell Publishing. (Original work published 1974)

Leung, C., Elkin, D. K., Norah, W.

X., & Suntikul, W. (2021, August 20). Inequality in Development Futures:

Tourism Economies Construction Technology in Tai O, a Village near Hong Kong.

Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture. https://www.acsa-arch.org/chapter/inequality-in-development-futures-tourism-economies-construction-technology-in-tai-o-a-village-near-hongkong/

Lynch, R. A. (2011). Foucault's theory of power. In D. Taylor (Ed.), Michel Foucault: Key concepts (pp. 13-26). Acumen Publishing. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/michel-foucault/foucaults-theory-of-power/FDBA0D73DFE14C6AEE665C14FB26DAA2

Ma, E. (2015). The 'unbearable' beauty of a cultural village: Performing and negotiating heritage in Hong Kong's Tai O. Tourist Studies, 15(1), 58–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797614561025

Mak, K. (2011). Community participation in tourism : a case study from Tai O, Hong Kong. https://doi.org/10.5353/th_b4642931

South Development and Sustainable Lantau Office - Improvement works at Tai O. (n.d.).https://sslo.cedd.gov.hk/en/our-projects/local-improvement-works/tai-o/index.html

Tai-o.com.hk. (n.d.). Fishing

culture and activities in Tai O [Photographs]. https://www.tai-o.com.hk/fishing-culture

Tai O Fishing Village. (n.d.). Lantau Island. https://www.lantau-island.com/tai-o-fishing-village

Wan, Y. K. P., & Chan, S. H. J. (2013). Social capital and community participation in tourism planning in Tai O, Hong Kong. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(6), 836-854. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.750369