1. Introduction

The Flower Market, or

“Fa Hui”, Hong Kong’s largest retail flower hub adjacent to Mong Kok Stadium,

is a vivid cultural trace that aggregates over 100 floral and horticultural

retail stores, connecting flower farmers with consumers (City Unseen, 2025).

Rooted in Chinese

traditional auspicious symbolism, it inherits the colonial-era “market”

concept, with flowers carrying blessings tied to major festivals—such as

kumquat plants for prosperity and daffodils for good fortune. Dating back over

130 years, flower farmers have sold blooms near the current Boundary Street

(then the Sino-British border) before the 1898 New Territories lease (Wu et

al., 2022). Its prime urban location has evolved from a spontaneous gathering

of farmers into an iconic market. Today, modern flower shops, as a

representation of space, representational space, and spatial practice

conceptualized by Lefebvre (Lefebvre, 2012), have reshaped the landscape,

including traditional wholesalers struggling amid competition from chains,

target audiences having shifted, and the market transforming from a

festival-centric spot to an all-year-round attraction, with new practices like

auctions emerging alongside domestic and overseas competition.

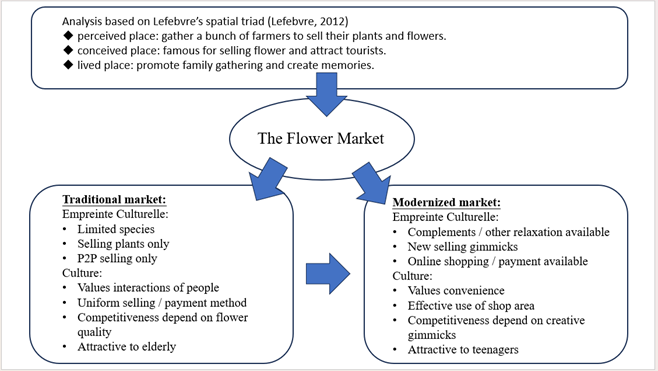

This study employs Lefebvre’s spatial triad and the concept of cultural traces to analyze how modernization and tradition interact in this space, exploring the cultural and geographical dynamics behind the flower market’s transformation.

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

The empreinte culturelle (文化印記) observed in the flower market reflects that the value of flowers for the people of Hong Kong has been changing over the years. The term “empreinte culturelle” is a French word meaning “cultural imprint,” which refers to the human activities, symbols, or architectures that reflect the opinions and values of humans living in a specific geographical area (Chen et al., 2025). The flower market originated by a small group of farmers who wanted to make a living by selling flowers to men looking for prostitution (City Unseen, 2025), but then changed to a site where everyone can buy plants for home decoration and a self-hobby.

Apply Lefebvre’s spatial triad (Lefebvre, 2012) in this place, the flower market is not only a perceived place that shares the majority of Hong Kong’s flower market, or a conceived place contributing to Hong Kong’s tourism, but also a lived place, which implies relaxation, blessings, and happiness for many local people. This is because giving flowers to your beloved means “wishing you a happy and fortunate future” in Chinese culture, especially in celebrating festivals or birthdays, which initiates people visiting the flower market and bringing this luck and blessings to their family, friends, or neighbours. Enjoyable memories and a sense of belonging were therefore linked to this traditional market.

3. Empirical Analysis

In the empirical

analysis section, our group identified six main differences through interviews

and observations, including the division of imported flowers, product

categories, running style, commercial methods, selling features, and space

division, which were retrospectively analyzed.

First, there are

differences in the types and styles of flowers sold between traditional flower

shops and modern ones. After the signing of the Treaty of Nanking in 1842, the

British introduced the culture of flower appreciation to Hong Kong (City Unseen,

2025). Fresh flowers such as gladioli and lilies are available throughout the

year. Most local flower farmers sell only one or two types of flowers a year.

Due to the limited living space in Hong Kong, there is insufficient space to

place New Year flowers (City Unseen, 2025). Through observation, a wide variety

of affordable small plants have been added to the flower market, such as

succulents and foliage plants. From the perspective of cultural geography, the

differences and changes in the types and styles of flowers are influenced by

foreign cultures and urban development. The limited living space has led to the

gradual decline of the flower appreciation culture, which is being replaced by

plant types that better meet modern needs.

Second, the product

categories change with market preferences. In the early 20th century, the

demand for flowers increased. The product categories in the flower market were

limited, and most stalls only sold flowers to meet the demand. Whether it was

common flowers like violets and roses, or New Year flowers like peach blossoms

and narcissus before the end of the year, the focus was mainly on flower sales.

Now, mixed businesses have emerged, combining flower shops with coffee shops,

allowing customers to appreciate flowers while enjoying coffee and desserts. In

addition, the products have also expanded to related products such as gardening

tools and decorations. From the perspective of cultural geography, the change

in the types of products is driven by consumers' needs. It is no longer limited

to the flowers themselves but places more emphasis on cultural experience and

leisure use.

Third, the running style has changed due to power. In the past, most flower

farmers sold flowers in the form of street stalls without fixed stalls.

However, in 1938, the Health Bureau required flower sellers to hold a hawker's

license, which led to the first transformation of the running style. Thus, in

1947, the running style of the flower market became a wholesale market with

fixed spaces, and a trade union was responsible for the management of the

flower market and the rent of the stalls. In the 1980s, a large number of

inexpensive fresh flowers from the Chinese mainland were imported into Hong

Kong, resulting in the second transformation of the running style. The stalls

were gradually replaced by systematic retail stores, and this situation continues

to this day. From the perspective of cultural geography, the transformation

from unplanned street stalls to a designed and planned consumerist landscape of

the flower market is beneficial to the development of the tourism and retail

industries. Meanwhile, the success of this transformation also symbolizes the

importance of power over space.

Apart

from the difference in running style, the division of the spaces between

traditional and modern flower shops should not be overlooked. While traditional

flower shops only divide areas for selling and decorating flowers, modern

flower shops include various areas inside the shop. After conducting interviews

and a field trip in the Mong Kok flower market, our group has found that modern

flower shops are created in mini cafes, handicrafts workshop classrooms, and

photo-taking areas, to attract more potential customers and increase their

profit. Due to the concerns of limited shop space in Hong Kong, modern flower

shops should recreate the spaces to maximize their products and services.

4. Conclusion

In

conclusion, this study employs a cultural geography perspective to reveal the

connections between Hong Kong's geographical context, Chinese floral culture,

and the transformation of Mong Kok Flower Market. The market's strategic

position, bridging mainland China and the global market, coupled with the rise

of consumerism, has driven its evolution from traditional wholesale operations

to modern diversified business models. The core logic of this phenomenon

emerges from the dynamic interplay between cultural imprints and spatial

production.

Lefebvre's spatial triad and cultural traces concepts were instrumental in interpreting this phenomenon, the former framing the market as perceived (wholesale bustle), conceived (touristic planning), and lived (emotional blessings), while the latter capturing the continuity and transformation of auspicious symbolism and modern experiential demands within floral culture, offering a critical framework for analyzing its geographical-cultural roots.

To balance traditional preservation with modernization, the study proposes a "Flower Market Cultural Conservation Initiative", subsidizing digital transformation for traditional flower shops to preserve their wholesale advantages and cultural identity, while establishing cultural exhibition zones to preserve symbolic meanings through festive markets and floral art workshops, ensuring the market's century-old cultural legacy thrives through innovation.

ReferencesCity Unseen. (2025, April 7). Origins to edges: How local farmers were pushed to the flower market’s margins. https://cityunseen.hk/flower-market-past-and-present/

Chen, Y., Jiang, E. J., & Mo, P. L. L. (2025). Does a founder’s cultural imprint affect corporate ESG performance?. Research in International Business and Finance, 76, 102800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2025.102800

Lefebvre, H. (2012). From the production of space. In Theatre and performance design (pp. 81-84). Routledge. https://philpapers.org/archive/LEFTPO-4.pdf

Graph (2025). Made by our group.

Wu, Q. T., Chen, Z. K., & Chen, J. M. (2022). 根莖葉花—花墟的記憶與想像 [Roots, stems, leaves, flowers: Memories and imaginations of the flower market]. https://hkbookcentre.uk/building-cityscape/Memories-and-Imaginations-of-Flower-Market/