1. Introduction

This project examines Temple Street, a historical and cultural landmark in Hong Kong, well known for its vibrant night market and rich traditions. Temple Street serves as a cultural landmark, reflecting Hong Kong’s transformation from a colonial trading hub to a modern metropolis while preserving elements of its local heritage. The street’s evolution — from a working-class marketplace to a tourist attraction — deserves its attention as it highlights the tensions between modernization and cultural preservation.

Situated in densely populated Kowloon, Temple Street’s strategic location and socioeconomic diversity have shaped its role as a public space. The street embodies Hong Kong’s hybrid cultural identity, blending traditional Chinese values with urban modernity. This project draws on concepts such as place-making and cultural trace theory to explore how Temple Street connects its geographical context with cultural practices through conducting interviews and observation in a site visit, offering insights into the interplay of heritage, space, and identity in a rapidly urbanizing city.

Figure 1. Temple Street Archway

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

From a cultural geography perspective, cultural traces in a place reflect the dominant cultural order, shaped by the interaction of socio-economic forces, power dynamics, and spatial transformations. These traces, whether preserved, modified, or erased, embody the evolving relationships between social groups and their environment (Anderson, 2021). As cultural orders shift over time, previously dominant practices may be marginalized, commodified, or replaced, creating a layered cultural landscape. In Temple Street, the forces of tourism and the transformation of entertainment culture have significantly altered its identity, displacing local practices while introducing new ones.

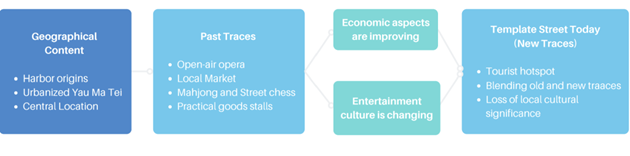

Figure 2. Illustration of the relationship between Culture and Place

Historically, Temple Street was a grassroots cultural hub for the working class, with Cantonese opera, mahjong, and street chess reflecting a communal entertainment culture. However, the push for urban modernization and global tourism has transformed it into a tourist-focused marketplace, erasing many traditional elements. Economic pressures have reshaped Temple Street, with local practices adapting to tourist demands. Informal street performances, once rooted in traditional storytelling, are now staged acts for visitors. Similarly, fortune-telling, once a meaningful spiritual service, has become a commodified, exoticized experience.

The entertainment culture of Temple Street has also evolved in response to these changes. Traditional practices such as mahjong and street chess, which fostered social bonds within the local community, have largely disappeared due to the loss of communal spaces. In their place, karaoke bars, VR arcades, and other forms of modern entertainment targeting younger audiences and tourists have emerged, reflecting the commercialization of leisure.

Figure 3. Project analytical framework

3. Empirical Analysis

The change in the way of leisure is an important factor that should not be overlooked in the transformation of the cultural landscape of Temple Street. At the beginning of the last century, Yung Shue Tau's harbor culture formed the initial trading of daily necessities by hawkers to the sea people. With the acceleration of urbanization in the mid-nineties (“香港記憶 | Hong Kong Memory”), inexpensive leisure and recreational facilities were needed and welcomed by the underprivileged. Some of the stalls selling daily necessities evolved into Temple Street Market, which was a popular entertainment place option for people at that time. People's interest in the marketplace also led to the emergence of a large number of businesses of various trades and industries in the Temple Street area. Popularity of traditional divination stemmed from Lingnan culture's emphasis on commercial transactions in expectation of favorable business development ahead. On the other hand, apart from Cantonese opera, drama, and storytelling, which were popular forms of entertainment nurtured by the Lingnan culture at that time, social connection was particularly prevalent. Families, friends and colleagues gather and chat as part of their nightlife, savouring local cuisine namely hotpot, seafood, dessert and other street food through the night at stalls in the middle of Temple Street. The successive emergence of these diverse cultural traces and their steady development over a long period of time were products of the interactions between the Hong Kong harbor region and its local cultures. Not only did they provide people at that time with a myriad of choices of entertainment and life experiences, but also formed a rich material and folk culture, as well as a technical arts industry in Temple Street.

Figure 4. Food stalls in the 1960s

In contrast, today's leisure options are even more abundant and diverse (“香港記憶 | 街坊集體記憶”). The electronic entertainment that young people enjoy without stepping out of their doors has replaced the habit of gathering at the open space at Yung Shue Tau to listen to performances. The government has offered more space, for instance, Yau Ma Tei Community Centre Rest Garden outside Tin Hau Temple, for residents to rest, socialize, and relax in the city centre. Nonetheless, it trivialized the space for entertainment in the original Temple Street. Nowadays, the emergence of contemporary cultures have led to the competition between traditional Cantonese opera and new popular music (劉, 何, 2005); the competition between convenient e-commerce and bazaar shopping; and the competition between new shopping malls and entertainment venues of old stores. Together with the issue of aging and loss of population in Temple Street (劉, 何, 2005), the change of Temple Street's traces have been escalated. For instance, the addition of up-to-date products and merchandise including IT gadgets, incorporation of Western fortune telling means namely tarot cards, are spotted during the site visit. The combination of old and new marks has transformed Temple Street into a place that now serves the tourism industry.

Figure 5. Integration of foreign fortune telling (Taken during site visit)

The second reason we believe Temple Street has undergone significant changes is the economic aspect. Shopkeepers have experienced lower incomes. Referring to a documentary on Temple Street in 2005, sellers of glasses and watches share a similar point of view.

Before 2000, there were cinemas and piers, so people used to gather there. However, after 2000, there were no cinemas or piers anymore, and the competition between shops intensified with the creation of large shopping malls (劉, 何, 2005) .

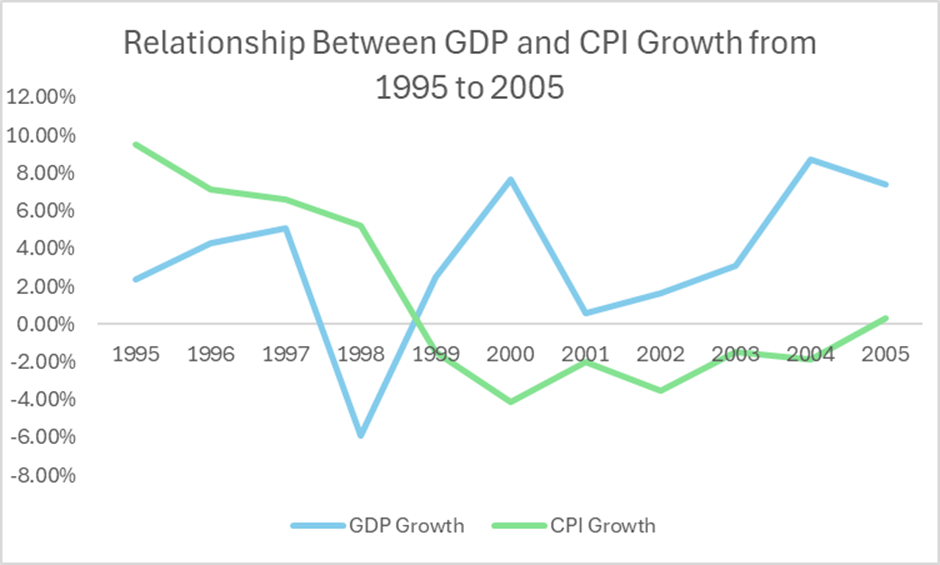

According to the 2000 Hong Kong yearbook, following a moderate recovery since 1999, local consumer spending saw more significant improvements in 2000. The rise in employment numbers, real growth in labor income, and the price discounts offered by retail stores all contributed to rekindling consumer interest. Private consumer spending showed a steady real growth of 5.4% in 2000, compared to a mere 0.7% increase in 1999 (Information Services Department, 2000).

Figure 6. Chart about the relationship between GDP and CPI from 1995 to 2005

Moreover, from 1998 to 2004, Hong Kong experienced deflation (Hong Kong Inflation Rate, n.d.), leading to generally lower prices. Consequently, people began choosing nearby shopping malls and a new street called the “Ladies' Market” over Temple Street, which was often referred to as the “Poor Man's Night Club.” This shift resulted in decreased foot traffic in the area. Additionally, as the mainland market opened up to Hong Kong, Lai, a glasses shop owner, mentioned that he could only sell 2-3 glasses in an hour or sometimes none at all, compared to selling 10 previously (劉, 何, 2005).

We can see that the culture, the economy of the street, and even that of Hong Kong have changed, affecting people’s shopping modes, behaviors, and thoughts. These changes are reflected in the income of shops and foot traffic. In order to address these challenges, new traces have emerged.

Due to unsatisfactory economic conditions, the chairperson of the Yau Ma Tei Temple Street Association successfully applied for shops to open in the afternoon, not just at night, to attract more people. Temple Street has also diversified its products, ranging from selling fruits and “doggie's noodles” to electronic watches and unique handicrafts to attract tourists and locals alike. It has even transformed into a part-time pedestrian area to limit vehicular traffic (劉, 何, 2005). The composition of these new traces has, in a way, created a new Temple Street and imbued it with a fresh significance. It is no longer just a local destination but has also become a renowned spot for tourists.

Table 1. Summary table of cultural changes through observation & interview

4. Conclusion

Overall, this project reveals the transformation of Temple Street through interplay between geographical location, cultural heritage and socio-economic forces. The comparison between past and current traces entails modernization and economic prosperity, which have considerably altered the traces in Temple Street, converting its identity from a local landmark with rich cultures into a tourist destination. In light of this, part of conventional practices disappear under the impact of tourism and commercial activities. Notwithstanding the significance of rapid tourism development, it is suggested that policy planning and interventions should cater to a balance of cultural preservation. For example, as reflected by the interviewee, initiate and promote authentic cultural practices without entirely adapting to the current trend of commodification. Consequently, the drawbacks brought by the aforementioned factors can be mitigated while retaining Temple Street as a representative of Hong Kong cultural hub.

Hong Kong Inflation Rate. (n.d.) Trading Economics. https://tradingeconomics.com/hong-kong/inflation-cpi (23 Nov 2024)

Information Services Department. (2000) Hong Kong Yearbook 2000: Economic-The Economy in 2000. Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. https://www.yearbook.gov.hk/2000/b5/04/c04-02.html (20 Nov 2024)

Hong Kong Memory. (2012). 香港記憶 | Hong Kong Memory. https://www.hkmemory.hk/MHK/collections/MemoriesWeShare/about/index_cht.html (23 Nov 2024)

Hong Kong Memory. (2014). 香港記憶 | 街坊集體記憶-活動-娛樂消遣-看電影是流行的平民娛樂. http://www.hkmemory.org/ymt/text/index.php?p=home&catId=503&photoNo=0 (23 Nov 2024)

Information Services Department. (2000). Hong Kong yearbook 2000: Economic – The economy in 2000. Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. Retrieved November 20, 2024, from https://www.yearbook.gov.hk/2000/b5/04/c04-02.htm

Yau, F., & 王冠豪 (編輯). (2021). 油尖旺本土文化風物誌 (第一版). 間築社有限公司.

劉瀾昌., 何錦燦., Asia Television Limited, & Asia Television Limited. (2005). 廟街榕影.

梁濤, 香港. 市政局., & 香港. 市政局. (1993). 九龍街道命名考源 = Origins of Kowloon street names .市政局.

蕭國健. (2006). 油尖旺區風物志 (第4版.). 油尖旺區議會.

李子建, 蒲葦, 鄭保瑛, 拾慧, 梁操雅, 許景輝, & 區婉儀. (2022). 我們的油尖旺故事 (初版.). 中華書局.