1. Introduction

The Tao Fong Shan Christian Centre in Hong Kong was

built in 1930 as a Christian church to propagate the Christian faith to the

Buddhist and Taoist communities in Hong Kong. The site was privately owned by

missionary Karl Ludvig Reichelt, whose unique religious understanding led the

complex to emulate ancient Chinese architectural styles, boldly integrating

Chinese dojos, schools, gardens, with the symbolic Christian cross. This

project aims to explore the role and influence of the site's religious and cultural

elements on the integration and development of Christianity in the Hong Kong

community. This project analysis draws on the theory of cultural diffusion and

glocalization to examine the diffusion dynamics through cultural

differentiation and the formation of these cultural landscapes.

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

Cultural geography perspective looks into the communication between different cultures and the traces it left for a place that may form its own sense of place and cultural expression. From cultural geography, cultural diffusion theory explains how cultural elements, such as ideas, practices, and technologies, spread through interactions among cultures, often moving from developed to developing nations (Coşkun, 2021). It distinguishes between hierarchical diffusion, where influential individuals disseminate ideas, and contagious diffusion, which spreads more broadly (Coşkun, 2021). Local cultures respond to these influences in various ways, shaped by their unique historical and social contexts (Coşkun, 2021). Outcomes of these encounters can be enriching—introducing beneficial innovations; or detrimental, potentially eroding traditional customs (Coşkun, 2021). Additionally, blending cultural elements can create hybrid identities (Coşkun, 2021). In the context of globalization, the theoretical term glocalization merges “global” and “local” to capture the interaction between global and local forces, showing how local contexts are influenced by global trends while reshaping those trends through local practices (Roudometof & Carpentier, 2020).

This project explores the tension in Tao Fong Shan’s cultural landscape, where global Christian influences intersect with local architectural and religious traditions. Established by missionary Karl Ludvig Reichelt, the center embeds Christianity within the diverse religious milieu of Hong Kong and broader China. As a pivotal site for cross-cultural dialogue, Tao Fong Shan exemplifies cultural diffusion by adapting Christian ideas to engage with local Buddhist and Taoist traditions, which demonstrates the processes of adaptation and hybridization that shape Hong Kong’s spiritual landscape.

3. Empirical Analysis

Tao Feng Shan was located north of

today’s Shatin station. It’s only a 25 minutes walk from today’s MTR station.

The nearby village Pai Tau Tsuen appears to have strong Buddhist cultural

traces , with temples like Po Ming Yuen and Ten Thousand Buddhas Monastery.

Here we clearly see the co-existence of Christianity and more local religions

like Buddhism. Rather than creating an East-and-West contrast , the Norwegian

missionary used a Buddhist-influenced mix of Chinese architecture style to

attract local people.

Figure 1. The road signs along the way up to Pai Tau Tsuen. (source: Authors)

In the bigger context of Hong Kong, this Chinese-style Christ Church reveals a unique blend of cultures, a phenomenon that bears traces of profound mutual influences and interactions.

Whether it is the history of British

colonization or the broad tolerance of immigrants and newcomers in modern

times, Hong Kong, as a city blending Eastern and Western cultures, carries a

rich history and cultural heritage, especially in terms of acceptance of

religious beliefs. It is in such a culturally diverse and friendly environment

that the Chinese elements incorporated in this Christ Church were nurtured, and

this phenomenon of cultural exchange is reflected in the architectural style of

the Christ Church. The Norwegian missionary, Karl Ludvig Reichelt, had

established the Jingfeng Mountain and Tianfeng Mountain Christian centers in

Nanjing and Hangzhou in the 1920s to 30s to entertain Buddhist and Taoist

apprentices. At that time, classical Chinese architecture was in vogue in

mainland China, and there was a tendency for Catholic and Christian churches to

abandon the classical Western style and build churches with Chinese elements to

bring them closer to the Chinese people. Reichelt moved his work to Hong Kong

in 1929 due to the war, and invited the Danish architect Johannes Prip-Moller

to co-design the Chinese style building complex. Reichelt's personal experience

and his dedication to bringing Eastern and Western religions into close

dialogue and exchange eventually gave birth to the Tao Fong Shan Christian

Centre.

Figure 2. Huizhou-style architecture Ma Tou Wall. (Sources: Authors)

Tao Fong Shan Christian Center can be summed up as a ‘Western vision of Chinese architecture’. From the characteristic Ma Tou (horse-head) walls and white walls and gray tiles of Huizhou-style architecture (Figure 2), to the cave doors and inscriptions of Soochow-style garden, as well as the classic features of traditional Chinese architecture, such as the dragon and auspicious cloud motifs, and the pavilion structure linking up the building complex.

Figure 3: Courtyard and Temple (圣殿). (Source: Authors)

Figure 4: Chinese-style corridors connecting yards. (Source: Authors)

As a whole, the mixing of different architectural styles in this complex is not harmonious, but is more like an accumulation of elements. Besides, in the traditional Chinese architectural layout, the complex is composed of a number of buildings and courtyards in a harmonious way, while most of the Western buildings are independent, highlighting the shape and beauty of the individual. It is clear that the builders did not consider the overall harmony of the Chinese style, but rather used Western architectural aesthetics and ways of thinking for the layout and design.

Figure 5: Eaves and ridge beasts. (Source: Authors)

From the details, it is obvious that these buildings show that the builders and designers only wanted to use the Chinese architectural style as a framework to build an innovative, East-meets-West architectural complex. For example, in Jiangnan, the eaves formed by the stacking of tiles are a special feature due to the region's constant rainfall. However, in the Sheng Dian temple at Tao Fong Shan, we can see that the stacked tiles on the eaves are only similar in shape to the impression of Chinese tile eaves, but not the actual use of the correct technique. Such problems can be seen in the beams and columns of the building (Figure 5) as well as in the construction of the flying eaves (飞檐), where the designers did not think about using actual Chinese architectural techniques, but rather imitated its features with western, modern architectural stylistic technologies.

Figure 6: Chinese-style roof and cross of the temple (圣殿). (Source: Authors)

Whether it is Chinese style or Western perspective, the geographical environment not only shapes the architectural style of this Christian church, but is also influenced by the phenomenon itself, reflecting Hong Kong's identity as a place of cultural integration. Hong Kong embraces and carries a wide variety of religions brought by foreign nationalities and populations, and harmoniously localizes these religions from all over the world, showing the local cultural imprint and the huge energy created in the process of globalization, and creating new power and space while integrating and shaping. Reichelt visualized the connection points between religions through innovative architectural forms. Perhaps influenced by the trend of localization of foreign religions in the mainland in the early 20th century, he chose to use the architectural perspective of Christianity and the West to express the concept of architecture as an external structure in this complex. The architectural style of the Tao Fong Shan Christian Center in Hong Kong is eclectic, integrating Buddhism, Taoism, Christianity and court styles, reflecting its important role in the integration and dissemination of religious theology and local culture.

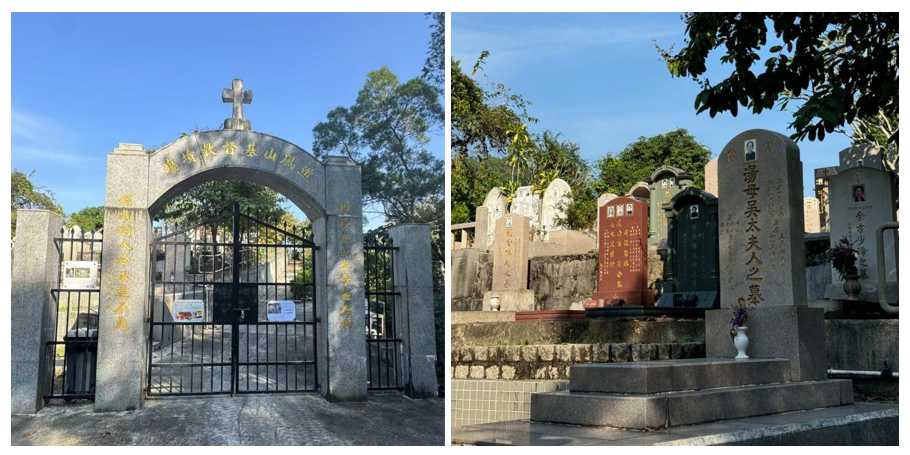

Similar to the buildings in the Tao Fong Shan Christian Center which clearly resembles a “buddhist Christian” style (Wang & Liu, 2024), where the negotiation of local and foreign power is clearly visible, the Tao Fong Shan Christian Cemetery was also built as a hybrid of the East and West. The gate of the cemetery is very representative in this respect. It had the traditional Chinese style of gate: one set of horizontally inscribed words up above (匾额), and then a couplet of words vertically inscribed onto the stones(对联). Like the main buildings, the architect take a chinese form, but aim to express christian meanings, because the couplet reads: Those who believe in me will never die, rebirth and life are both on me (信我的人永远不死,复活在我生命也在我). While general visitors were not allowed to go into the cemetery, a peek at what’s inside shows this is clearly a christian cemetery, where Cross is visible, although not present in every grave. While globalization through means of colonialism took place in Hong Kong, it led to cultural diffusion that’s indeed uni-directional as what Coşkun argued (Coşkun, 2021). The delicate strategy Christian culture spread was through making itself appear alike to local culture, or “taking up a local corporeal but having a western soul”.

Figure 7&8. The Gate and the graves of the Tao Fong Shan Christian Cemetery.(Source: Authors)

While all of our analysis tends to indicate that there’s this “western” power trying to disseminate christianity through assimilating into local, especially buddhist architectural forms and culture, we’ve noticed something reversal in terms of power relationship. Inside the Christian buildings there is this hand drawn map about Tao Fong Shan in tiles. It is particularly interesting because some tiles of the current painting had fallen off at the left corner and it shows the interior of that painting, which tells us that the current tile painting was painted on an old map of Tao Fong Shan. While the current map resembles a Chinese style painting and the words written in Chinese, the old map has its words written in English. On the current painting it reads: painted in 1963. In 1963 the Norwegian missionary had already died, which may mean the western colonial control in Tao Fong Shan had already weakened and the place was becoming increasingly Chinese. This act can be viewed as a response and even resistance to the colonial power and its cultural diffusion. Theories of glocalizations argue that when global forces meet local context, local culture will not only be influenced by the outside, but also have the power to resist and reshape the global cultural norms. In this case the resistance is not towards spreading Christianity through a Buddhist way, but rather the language “English”, which is also a culture that represents colonial power.

Figure 9. Map of Tao Fong Shan. (Source: Authors)

4. Conclusion

This paper analyzes in detail the cultural dynamics of the Tao Fung Shan Christian Center in Hong Kong under the interaction of global Christian influence and local religious practice through the theory of cultural diffusion and glocalization. This geographical landscape integrates Christianity with the multi-religious landscape of Hong Kong and China Mainland, reflecting the inevitability of the emergence of new cultural landscapes under the collision of different values, as well as the localization process of foreign cultures from a religious perspective. Although our group thinks the Chinese elements used in its architecture are lacking in balance and technical aspects. It is undeniable that the architectural style of the fusion of Chinese and Western still reflects the cultural tolerance and uniqueness of Hong Kong as a global city, reflecting the profound mutual influence and interaction with the geographical background, and the identity of Hong Kong's cultural diversity.

References

Coşkun, G. (2021). Cultural diffusion theory and tourism implications. International Journal of Geography and Geography Education, 43, 358-364.

Chen, Weitong. (2016, January). 香港沙田道風山建筑群. 汉语基督教文化研究所. https://www.iscs.org.hk/Common/Reader/News/ShowNews.jsp?Nid=1541&Pid=3&Version=0&Cid=334&Charset=big5_hkscs

Roudometof, V., & Carpentier, N. (2020). Translocality and glocalization: A conceptual exploration. In Handbook of culture and glocalization (pp. 324-329). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781839109010.00029

Wang, W., & Liu, Y. (2024). “Buddhist-christian style”: The collaboration of PRIP-Møller and Reichelt—from Longchang Si to Tao Fong Shan christian centre. Religions, 15(7), 801. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070801

道風山基督教叢林. https://www.tfscc.org/