1. Introduction

Miao

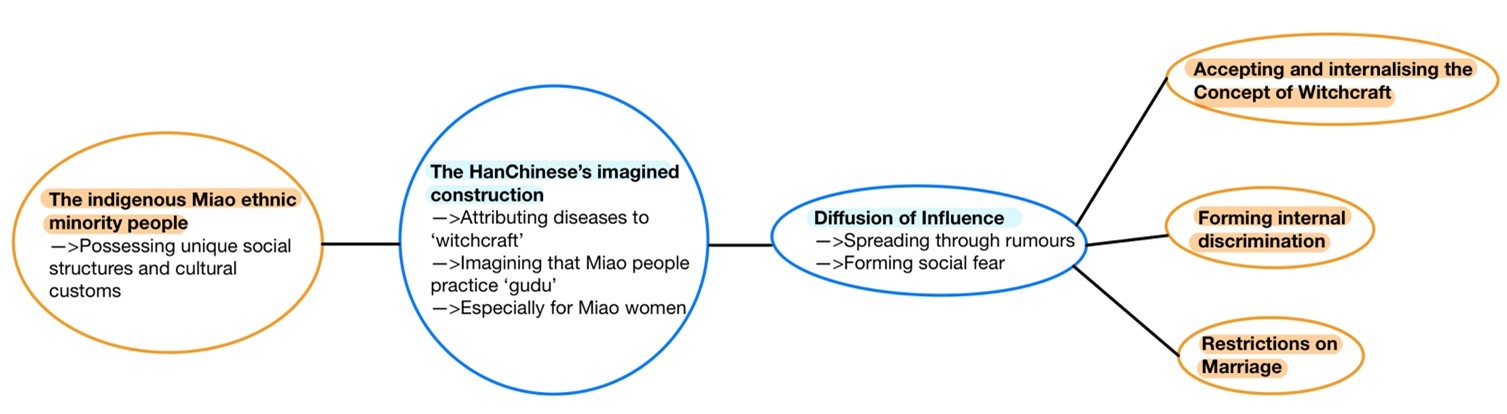

witchcraft, which has been a form of myth and religion, was stereotypically

defined by Han as a method of harming other individuals (Pan, 2005, pp. 1-2).

Han had developed this stereotype on behalf of the society in order to promote

social exclusion and solve the conflicts of interest between Han and Miao, thus

creating misunderstandings and extreme imagination (Pan, 2005, pp. 1-2). During

the 16th-19th century, in Western Hunan, Han's ruler wanted to create

Mechanisms of spatial management and cultural control, in order to fulfill this

purpose, Han constructed stigmatisation on Miao's witchcraft. Miao's witchcraft

has shown the power struggle between Han and Miao, Han utilised witchcraft as a

method to suppress Miao's status, raising the tension between their power

relations (Pan, 2005, pp. 3). The following paragraphs describes how the

Han-Miao power struggles shaped witchcraft's concept and applications, and how

these power relations manifested in accusations and social control.

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

To begin with, cultural geography has been

the study of life's varied richness and how people use and understand the

environment, space, and locations to maintain their culture (Crang, 1998).

Marks, vestiges, or leftovers left behind by

cultural life have been referred to as traces. Both tangible and intangible

traces, visible and unseen, permanent and transitory, might be present

(Anderson, 2015). Even if the original context has been lost or distorted,

these remnants have provided proof of the existence and significance of a past

moment. Trace-chains have revealed hidden histories and patterns by connecting

locations into networks of similarities and contrasts (Anderson, 2015). It

revealed how Han people's stereotypes of the Miao people were preserved and

transmitted through both tangible and intangible forms.

Moreover, transgression has involved

deliberately crossing or violating established boundaries, whether legal,

moral, or normative (Anderson, 2015). Transgressors have willfully disregarded

the boundaries established by those in positions of power, refusing to be bound

by norms or regulations. By doing this, they have provided new opportunities

for identity development, self-expression, and social change. The Miao people

were viewed as disruptors of Han cultural norms. The Han people interpreted the

Miao's lifestyle, religious beliefs, and social organizational methods as

violations of mainstream cultural order.

Lastly, resistance power has referred to the

deliberate act of opposing, challenging, and resisting authority, and

attempting to change the memory and culture of the ruling power structure,

abolishing the orthodox culture (Anderson, 2015). From minor acts of

disobedience to huge societal movements, this resistance has taken many

different forms. The goal of resistors has been to sabotage the efficient

functioning of power by highlighting its prejudices and constraints and

creating new avenues for opportunity. Revealed how the Miao people demonstrated

their subjectivity within this special politics.

3. Han Chinese Historical Perceptions of Witchcraft and Social Control of the Miao People

From a cultural geography perspective, the geographic environment played a crucial role in shaping the Han people's perspective about the Miao people's poison sorcery, demonstrating a transformation process from natural space to sociocultural space (Wu, 1942).

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the migration of Han people into the southwestern regions led to spatial anxiety when confronting drastically different geographical environments (Wu, 1942). This manifested primarily through disease: unfamiliar climatic conditions, dietary habits, and biological environments caused Han people to contract many unknown diseases. The Han blamed these naturally occurring diseases on Miao’s "poison sorcery," such as snake, lizard, and centipede-based poisons (Pan, 2005, pp. 26-28). They attributed the dangers encountered during migration to the southwest to ethnic minorities. This process of stigmatization reflected how rulers utilized environmental differences to construct cultural hegemony.

Furthermore,

Han people leveraged the southwestern region's geographical characteristics to

categorize the Miao into "civilized Miao" and “unacculturated

Miao," distinguishing between controlled and uncontrolled Miao groups for

implementing differential governance (Zhang, 2020, pp. 6-7). This relegated the Miao people to a

marginalized geographical position and established spatial segregation. This

process manifested not only in policies but also in folk literature, such as

government bans on Miao writing, fantastical folk novels written in Chinese,

storytellers' fabricated tales, and the gradual formation of public fear and

stereotypes about Miao shamanic practices (Pan, 2005). It was also reflected in

cultural expressions like clothing patterns. For instance, the horizontal lines

representing rivers and square patterns representing farmland on Miao women's

clothing recorded their migration trajectory of being driven from the Central

Plains to the borderlands by the Han (Zhang, 2020, pp. 5-6). The patterns are not only the

representation of forced domination but also interpreted to preserve cultural

memory and hidden resistance. Through these means, geographical differences

were transformed into cultural hierarchy narratives, becoming significant

guidelines for Han people to established and maintained their cultural

hegemony.

4. The Stigmatization of Miao Women in Han Culture

In addition, the Han people's

perceptions of the Miao people's shamanism and witchcraft particularly revolved

around women (Wu, 2006). The first reason was that, within the discourse system

of the patriarchal society of the Han people, Miao women exhibited characteristics

of transgression. For example, the Han society upheld concepts such as

"three obediences and four virtues" and the belief in male

superiority over females (Pan, 2005, pp. 33). However, in Miao society, women

enjoyed a higher status and autonomy, not limited to the fixed roles of

"men farming and women weaving". They could move freely, possessed the

freedom to choose their partners, inherit property, and held specialized

knowledge in fields such as healthcare and religion (Pan, 2005, pp. 7-34).

These behaviors transgressed the established gender order in Han culture,

provoking anxiety among the ruling class (Pan, 2005, pp. 33-34). Therefore, Han

society demonized and stigmatized Miao women by associating these activities

with witchcraft, aiming to uphold the dominant culture.

The second reason was that Miao women, as cultural others, inherently embodied a form of resistance. Consequently, Han society responded to this resistance by constructing a stigma associated with "witchcraft." First, Han society demonized the outward physical characteristics of Miao women by emphasizing traits such as red eyes from cooking, excessive body hair, and shiny foreheads. This malicious portrayal transformed ordinary Miao women into witch-like figures in order to establish boundaries. (Pan, 2005, pp. 29-32). Secondly, Han society linked the cooking practices of Miao women with witchcraft and poison-making, thereby establishing a stereotype that portrayed Miao women as dangerous (Pan, 2005, pp. 47). Finally, Han society connected Miao women with ancient shamanic and witchcraft cultures, defining their practices as evil and assigning them immoral labels to rationalize discrimination (Pan, 2005, pp. 7). The accumulation of these three layers of stigma has created a complete chain of stigma, deepening from physiological characteristics to behaviors and then to morality, firmly imprinted in the minds of everyone. It has been evident that this was not merely a matter of cultural prejudice; rather, it represented a process of constructing the cultural other within the discourse of power.

5. The negative effects to Miao society by the stigmatization of witchcraft

In ancient times, Miao people believed

all objects, places and creatures possessed divine essence, and those spirits

controlled all natural phenomena (Wu, 2014). To avoid natural disasters, the

ancestors of the Miao people had created rituals such as offerings and

sacrifices to please the spirits (Wu, 2014). Agriculture later became a major

part of the economic systems of ancient Miao people, and it had contributed to

Miao people's needs for excellent natural resources and climate, hence the

elementary rituals they constructed were passed on and became Miao's witchcraft

(Wu, 2014).

Despite having strong cultural roots,

the Miao witchcraft tradition has been gradually fading as young Miao people do

not take it seriously due to cultural invasion (Wu, 2014). The origin of the

Chinese word for witchcraft could been found in Shuowen Jiezi (Wu, 2006).

Originally referring to insects that were formed from decaying materials, such

crops, the word has since evolved to signify something deadly and enigmatic. In

the beginning of the Liberation of China, many Miao people still had strong

belief in their witchcraft, and it caused Han people to panic or despise them

(Pan, 2005). After the government's attempt to educate the public about

superstitious and stop false accusation on witchcraft in 1950s, the number of

witchcraft charges against Miao people decreased. However, the aggression

towards them had become more subtle (Pan, 2005). Younger Miao people who

experienced Han style education became estranged from traditions (Wu, 2014).

Many of them simply viewed witchcraft as superstition, nothing more than an

artistic expression and entertainment (Luo, 1993).

Moreover, the stigmatization of

witchcraft by Han people has led to sexism and repulsion towards their

traditions (Wu, 2006). With the Chinese proverb, "illness enters the body

through the mouth", Han made Miao

witchcraft was frequently associated with women as they oversaw cooking

typically. Gave rise to numerous allegations accusing Miao women of witchcraft

(Pan, 2005). This has led to hatred and loathed against Miao women and unequal

treatments towards them such as refuse to wed Miao women as men feared to be

"cursed" if they marry a Miao woman with witchcraft (Pan, 2005).

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, Miao witchcraft

represented the tribes' belief in supernatural beings and their use of

witchcraft as a method to combat illness and disease (Pan, 2005). It also has

served as a trace and marker of the Miao people's geographical and cultural

aspects, revealing the power struggle between the Miao and the Han. Despite

being a part of Miao culture, the Han have stigmatized it, resulting in

internal discrimination (Pan, 2005). It ultimately stemmed from the ancient Han

rulers' desire to dominate and control the Miao people, as they constituted the

majority (Wu,1942). The Han then used witchcraft as a "tool" to

subjugate the minority. We believe the government could foster an open society

where individuals of all ethnic backgrounds could appreciate one another's

cultures, even though we might not trust the rumors in the modern world.

Anderson, J. (2015). Understanding Cultural Geography: Places and Traces. Ch.1-3

Crang, M. (1998). Cultural Geography (1st ed.). Routledge. pp.3-12

Luo, Y., Perspectives of magic of Miao people in China, 1993, pp. 11-12

罗义群.(1993) 中国苗族巫术透视, 頁11-12.

Wu Bei, An Analysis of Information Dissemination Regarding Miao Witchcraft Beliefs, Journal of Chinese Ethnic and Folk Medicine, 2006, pp. 67-69.

吳蓓,<苗族巫蠱信仰現象的信息傳播分析>,<中國民族民間醫藥雜誌:2006年>,頁67-69

Wu Minglin, Research on the Witchcraft Culture of Miao Nationality, A Thesis Submitted to Chongqing University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Master‟s Degree of Literature, 2014, pp. 12-16

吴明林. (2014). 苗族巫文化研究 (Master's thesis, 重庆大学),頁12-16

Pan Wenxuan, Miao People and Witchcraft: Imaginations and Accusations of the Other, Master's Thesis, Central University for Nationalities, 2005, pp. 1-55.

潘文獻 ,<苗人、巫蠱:對於他者的想像和指控>,<碩士論文,中央民族大學 ,2005年>,頁1-55

Wu Zelin, Chen Guojun, Research on the Miao and Yi Societies of Guizhou. Jiāotōn Shūjú, 1942.

呉沢霖, & 陳國鈞. (1942). 贵州苗夷社会研究. 交通书局

Zhang Zhaohe,Between Evasion and Clinging: The Identity of the Miao People in Southwest China and the Politics of the Other, 2020, pp. 5-7.

張兆和.(2020). 在逃遁与攀附之间:中国西南苗族身份认同与他者政治 , 頁5–7