Spatial Conflict and Justice in Public Space

Figure 1.A homeless sleeps in Hong Kong public area.

(Source: Ming Pao)

1. Introduction

Yau Tsim Mong carries several characteristics contributing to the agglomeration of the homeless. It is one of the areas with the oldest buildings and the highest population density of 44,458 people per square in Hong Kong (HKSAR Census and Statistics Department, 2022), which contains multiple public facilities, such as a community center, park, sports field (Yau Tsim Mong District Council, 2015). It also has high accessibility as the hub of the central transport hub (Home Affairs Department, 2022). All these characteristics encourage the homeless to choose to stay in the Yau Tsim Mong areas. According to the area of distribution towards the homeless, most of the homeless are found in Kowloon, with an increasing number of 353 from 2015-2022(HKSAR Press Release, n.d.), while from the research from the Society for Community Organization, the research shows that there are 63% of homeless living in Kowloon West (Society for Community Organization, 2022). Under this observation, the project aims to investigate how the homeless use public spaces along the Yau Tsim Mong areas under the framework of social-spatial practice.

2. Theoretical framework

With the rising numbers of the homeless and their agglomeration in Yau Tsim Mong mentioned above, we would like to apply one of the cultural geographical perspectives - social-spatial practice, to show the usage of public space towards the homeless and how they cause spatial conflicts with the stakeholders. According to the spatial theory suggested by Henri Lefebvre, social-spatial practice is equal to the behavior of people in space, which is an essential element in shaping the spatial structure of their daily life (Chan, 2008). In the space where people live, the urban users occupy and develop their living space by using their bodies and assets so that people can create their own social spaces that fit their lives. In other words, the homeless in Hong Kong extend their own social space in public areas through their bodies which recognize their urban spaces according to the actual needs of their daily life. They have this social spatial practice to strive for more living or survival spaces in these public social areas. However, with the insufficient public spaces in Yau Tsim Mong, how do spatial conflicts between the stakeholders limit or impede the social-spatial practice toward the homeless? The following will be our analysis.

3. Empirical Analysis

Spatial Conflict

There are two stakeholders which could cause spatial conflicts with the homeless and compress the usage of public spaces. The primary stakeholder is the Hong Kong government. Since they are responsible for avoiding obstruction and environmental hygiene problems in society, living in public areas would be counted as violating the social order. Therefore, the government would take action to stop the homeless from extending their living area in public spaces. For example, the government would hold joint operations to clear miscellaneous articles in the subway connecting to Hong Kong Cultural Centre (HKSAR Press Release, 2021). The clearance proposed by the government does not allow the homeless to use public spaces, which hinders their social-spatial practice. Moreover, with the alignment of urbanization, the Hong Kong government strives to beautify the community, but the homeless count as detrimental to social appearance. Thus, the government made numerous hostile architecture (Zhao, 2022), such as benches with wavy slopes, packed handles, like photo shown in Figure 1, such designs of public facilities intentionally disallow the homelessness sleep overnight in public areas like parks. With such pressure from the government, they are forced not to stay in public areas where the homeless limit social-spatial practices.

Figure 2. An example of hostile architecture.

(Source: Yi Lei Lam, HK01)

Another spatial conflict is between the community and the homeless. People living in Yau Tsim Mong do not have enough recreational areas for their leisure time. Each Mong Kok resident owns only 0.6 square meters, which is far below the standard of 2 square meters per capita set by the government 15 years ago (HK01, 2017). Meanwhile, people regard the homeless as harming the appearance of the community. Therefore, there is a phenomenon of "Not in My Backyard" (Wasserman& Clair, 2011), the community does not welcome the homeless, and their social-spatial practice is furtherly limited under the spatial conflicts.

Public Space for Intercultural Mixing

Figure 3. Homeless sleep at night in Cultural Centre, Tsim Sha Tsui

(Source: HK01)

Public space is decentered, mobile, open-ended, and embodied (Qian, 2022, p. 78). In the multidimensional definitions of public space, it is no longer just loosely categorized as "spaces for the public" and "spaces for private" (Qian, p. 79). With the nature of Throwntogetherness, public space is a situational, performative structure with complete functionality in the urban realm outside the home and private spaces (Massey, 2005, p. 140). During the privatization of public space, the homeless redefine "Home" in redundant spaces (Tang, 2019, p. 449-459).

Hong Kong is a region of diversity and inclusiveness, tolerant of people of different genders, races, classes, etc. Hong Kong has a large amount of land mixed with different uses and buildings of different values sharing the same public space. At the same time, as a member of society, the homeless deserve to preserve their values, and it is a part of Yau Tsim Mong's geographical traces that cannot be ignored. In an ideal public space, people collide with each other with their values and cultures. In the process, the conflict will be slowly dissolved, and each member can grind away their societal differences (Dyer, 2008, p. 207-213).

However, social workers pointed out that it is becoming more and more difficult for the homeless to survive in public spaces (RTHK, 2012). They pointed out in the interview program that the government's policy of suppressing the homeless, such as driving homeless people by cleaning the streets, forced them to go to more secluded spaces, making it more difficult for social workers to visit.

Spatial Justice in Public Space

Different scales (physical to global) and domains (land, environment, gender, resources, etc.) exist in spatial production and cause spatial inequality. The concept of spatial justice regards space and society as one entity and tries to practice changing (Ye, 2019, p. 146-154). However, justice is a complex concept related to value judgment and morality without a unified meaning. But social justice means "everyone can get what they deserve fairly" (Yu, 2017, p. 5-14).

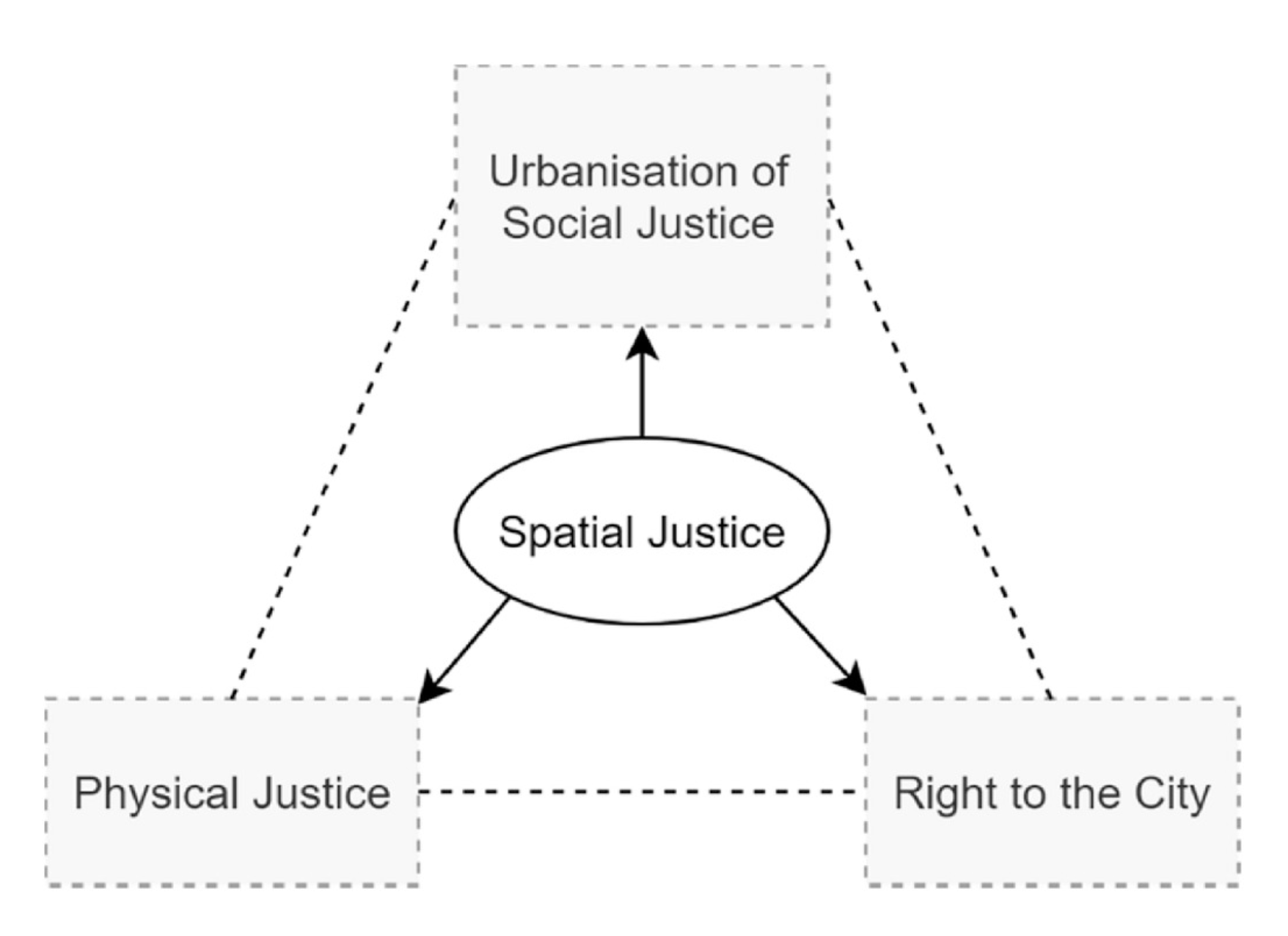

Figure 4. Spatial Justice from three aspects

(Source: Jian, Luo & Chan, 2020)

Regarding the understanding of everyone's rights in space (see figure 4), the right to the city proposed by Lefebvre (1968) noted that everyone should be able to live with dignity in the city. Hong Kong is a highly urbanized city, but its rapid development often ignores a small number of interests. As members of the community, in the inherent impression, the homeless can easily be intuitively perceived as socially inactive and disliked by their neighbors. However, for the right to the city of the homeless, they have the right to a dignified living space. The land issue in Hong Kong has multi-dimensional reasons, but it is an inevitable conflict to keep citizens living with dignity. In this case, everyone should have the right to access public spaces, including the homeless. Meanwhile, people should not ignore the demand of social spatial practice towards the homeless, so their dignity is considered.

Solving conflicts between the homeless and the public requires a comprehensive social system, and the problem cannot be solved solely by changing the use of space. Therefore, how to reserve space for the privatization of the homeless in the city becomes a problem. Public space has its order, and how to balance urban governance and spatial justice requires a more comprehensive and thoughtful plan.

4. Conclusion

To strive for more living and activity space, the homeless create a "home" with their bodies in the public space of Yau Tsim Mong District, practicing urban space. Coexisting with the homeless is supposed to present a culture of inclusion in Hong Kong. However, increasing spatial constraints make it difficult for the homeless to fight spatial conflicts and move to more secluded spaces. There are more and more restrictions on the daily space of the homeless, so open, flexible, and highly malleable public spaces and facilities are regulated. As the measures for public space are constantly changing and narrowing, at the same time, Hong Kong culture, which is supposed to be caring and tolerant, may be changing.

Reference

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Oxford: Blackwell.

HK01. (March 12 ,2017). 油尖旺冇地方hea?研究指旺角居民只有0.6平方米休憩空間. Retrieved November 29,2022 from https://www.hk01.com/%E7%A4%BE%E5%8D%80%E5%B0%88%E9%A1%8C/77262/%E6%B2%B9%E5%B0%96%E6%97%BA%E5%86%87%E5%9C%B0%E6%96%B9hea-%E7%A0%94%E7%A9%B6%E6%8C%87%E6%97%BA%E8%A7%92%E5%B1%85%E6%B0%91%E5%8F%AA%E6%9C%890-6%E5%B9%B3%E6%96%B9%E7%B1%B3%E4%BC%91%E6%86%A9%E7%A9%BA%E9%96%93

HK01. (August 24, 2018).公共設施設計如何影響日常生活? 還無家者一個家. Retrieved November29,2022.

https://www.hk01.com/article/226864?utm_source=01articlecopy&utm_medium=referral

Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Census and Statistics Department. (2021). 2021 Population Census, Summary Result. https://www.census2021.gov.hk/doc/pub/21c-summary-results.pdf

Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Press Release. (September 16, 2021). Government finishes joint operation to clear miscellaneous articles in subway connecting to Hong Kong Cultural Centre Retrieved November 29,2022 from https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202109/16/P2021091600424.htm

Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Press Release. (n.d.). 按地區劃分的露宿者人數[The number of homeless base on the district distribution] https://gia.info.gov.hk/general/202006/10/P2020061000398_343137_1_1591765001351.pdf

Zhao. J. (2022). An Inclusive Hong Kong through Public Spaces for Urban Homeless. Conference: International Forum on Urbanism. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339353397_An_Inclusive_Hong_Kong_through_Public_Spaces_for_Urban_Homeless

Society for Community Organization. (October 26, 2021). 全港無家者人口統計調查2021研究[2021 Research of Hong Kong Homeless Population in 2021] Retrieved November 29,2022 from https://soco.org.hk/rp20211026/

Wasserman, J. A., & Clair, J. M. (2011). Housing Patterns of Homeless People: The Ecology of the Street in the Era of Urban Renewal. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 40(1), 71–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241610388417

Yau Tsim MOng District Council. (2015, June 4). District Highlight. Retrieved November 29,2022 https://www.districtcouncils.gov.hk/ytm/tc_chi/info/highlight_01.html

陳露明. (2008). 空間 [Space]. 文化研究@嶺南 第十期. https://web.swk.cuhk.edu.hk/~hwong/pubfile/researchmonograph/2018_SSPDB_Streetsleepers_Chi.pdf

Qian, J. (2020). Geographies of public space: Variegated publicness, variegated epistemologies. Progress in Human Geography, 44(1), 77–98.

Dyer, S. (2008). Hybrid geographies (2002): Sarah Whatmore. In Hubbard, P., Kitchin, R. and Valentine, G. (Eds.) Key texts in human geography, 207–213.

Massey, D. (2015). For Space. London: SAGE.

Tang,K.-L. (2019). s of Public Space. Space and Culture, 22(4), 449–459.

Ye, C. (2019). The methodology on spatial justice and new-type urbanization[J]. Geographical Research, 38(1): 146-154

Yu, K., (2017). Rethinking equality, fairness and justice. Academic Monthly, (4): 5-14

Jian, I . Y., Luo, J., & Chan, E. H.-W., (2020). Spatial justice in public open space planning: Accessibility and inclusivity[J]. Habitat International, 97(2).

Cobb-Clark, D. A., Herault, N., Scutella, R., & Tseng, Y.-P., (2016). A journey home: What drives how long people are homeless?. Journal of Urban Economics, 57-72.