A study of Sham Shui Po’s spaces and cultures using spatial triad

1. Introduction

The unique neighbourhood culture in Sham Shui Po (SSP), one of the poorest districts in Hong Kong, has gained our interest. Despite the fact that Hong Kong is a well-developed financial city, SSP exists in Hong Kong as a slum with more than 25% population living under the poverty line1. Besides, it is the location where new immigrants, South Asians and local residents live together, leading to more collision between their own distinguishable culture and traces. Most underprivileged people in this region have to struggle for a living; therefore, their living style is more down-to-earth and goal-oriented without much leisure. However, it has been observed that more hipsters are interested in setting up their own business in this old town which is a peculiar deviation from the traditional culture of practicality of SSP residents. As a result, we have conducted research to probe into some questions that we found intriguing from SSP.

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

Our investigation revolves around the following research question: How did the residential and economic identities of Sham Shui Po change drastically behind the corresponding battle of powers? Is the recent trend healthy for Sham Shui Po?

Economic traits, as sellers and consumers of a region, largely reflect the values and cultures of the residents. This correlation is especially conspicuous when there is an opportunity to revolutionise an economy, i.e. when SSP faced industrial depression. To compare the differences in economic characteristics in SSP over the last few decades, Lefebvre’s spatial triad is applied to examine how various stakeholders and events during the process result in such a drastic turnaround.

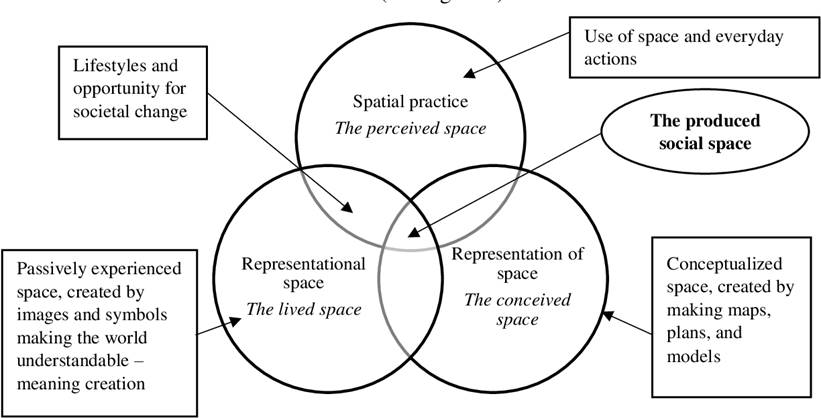

The spatial triad theory is composed of 3 components: spatial practise, representations of space, and representational spaces (Figure 1).

l Spatial space is the use of space and everyday actions.

l Representations of space are the conceptualised space created by making maps, plans and models.

l Representational spaces are passively experienced spaces created by images and symbols, making the world understandable, which means new creation.

Figure 1. An illustration of the spatial triad2

The spatial triad renders a framework to investigate the phenomena involving the domination of authoritative power and the confrontation of resisting power, which in turn bring forth the economic altercation that gives SSP a brand new image to the general public. On the other hand, it allows comparisons of the residents’ opinions and perceptions on the respectively old and new traces. Thus, we can particularly analyse how the new representational spaces impact SSP citizens.

3. Empirical Analysis

Representation of space in Sham Shui Po

Despite the rich culture that Sham Shui Po encompasses today, it was originally conceived simply to be a residential area. In the 40s, Sham Shui Po was a coastal region, whose residents engaged in agriculture, specializing in fishing, farming and trading (Figure 2). These made SSP a stable community with a low cost of living. Soon, many people fled to this place from mainland China due to the civil war, causing a housing shortage. Hence, many unauthorised and dangerous houses were built to accommodate the increased population, while tang lou

Figure 2. Sham Shui Po as an agricultural centre in the past3

Besides the housing shortage, the skyrocketed population decreased job opportunities due to labour surplus4. As most immigrants were low-skilled and poor people, they adapted to working or selling products as hawkers on roadside booths owing to affordable set-up costs. Regulation on hawkers was loose as the British government regarded it as welfare for the poor. Thus, roadside booths allowed hawkers to travel freely to reach the most crowded destinations and generate the most revenue. This trace is still preserved in modern SSP but in a more organised form. Financially challenged groups still have a strong demand for cheap electronic gadgets and other daily necessities from hawkers such as Apliu street. This remains as one of the prominent old traces of SSP even when the region has already changed drastically. Overall, the spatial practice of close neighbourhood and low-end stores and booths illustrated hospitality and down-to-earth lifestyle as its sense of place for SSP.

Representational space in SSP

However, the historical context has led to dramatic changes in the lived space of SSP. In the 1980s, China’s reform and opening-up led to the relocation of factories from Hong Kong to mainland China; the manufacturing industry in HK thus sank into atrophy. Although the retailing industry took over some spared roadside booths, the number of stalls was still in surplus. Therefore, rent in SSP was much lower than most other places in Hong Kong. In 2010, the emergence of cultural and creative businesses encouraged many young people to venture into the industry. Though they lacked capital, SSP was the perfect place for them as rent was much more affordable, while stall owners were enthusiastic to accommodate new tenants after decades of vacancy. This led to a paradigm shift in the economic composition of SSP, from low-end retailing shops to high-end stores like luxe coffee shops and boutiques. Consequently, many consortia, who valued profit maximisation instead of hospitality, began to invest in high-end private residential buildings in SSP.

However, in contrast to the British government, roadside booths and hawkers have become illegal under Hong Kong law after complaints from the business sector and cross-district citizens due to unfair competition and blockage of narrow streets. The government has launched several policies to suppress hawkers, including Public Health and Municipal Services Ordinance, Hawker Regulation and stricter patrol, pushing SSP to a new stage in viewing representations of space.

The government, new entrepreneurs and consortia were the absolute dominating powers in this power struggle. The poor and indigenous SSP hawkers, store owners and residents, being the resisting powers, could only offer limited confrontation to impede the rising cost of rent and housing. Residents and hawkers mainly lived in poverty; they had to work relentlessly to support the basic expenditure of survival needs; whereas the old shop owners valued hospitality and serving the underprivileged neighbourhood more than profit maximisation. They did not have the time, socio-economic status and bargaining power to resist the transitions faced.

Optimistically, the emergence of new cultural business and private housing, together with governmental intervention, did not eliminate the old traces and cultures. The introduction of high-end entities was not appealing to the poor residents of SSP. Stores and hawkers that sell cheap everyday products are still heavily relied on by impoverished residents, who are reluctant to move away from their current flats in tang lou. Hence, SSP remains one of the poorest regions in Hong Kong5. These old features are still standing today and remain characteristic of this region by the general public.

Spatial practice in SSP

Hence, the current mixture of low-end and high-end traces can be viewed as a phase of gentrification in this perceived space6 (Figure 3). Old traces still exist today but are fading away; for example, many old residential buildings have been demolished and replaced by new ones. Hawkers can only become active at midnight since the government chooses to take a blind eye during the desolate period of the day. Concurrently, freshly created graffiti and the Jockey Club Creative Arts Centre have brought art culture to this conservative place, whereas new cafes and creative businesses have widened the scope of goods and services provided in SSP.

Figure 3: the combination of old and new traces in SSP7

However, the trend of gentrification hasn’t shown signs of slowing down. Ongoing gentrification may eventually eradicate all cheaper shops and raise the price index. Underprivileged residents may have no choice but move to even poorer districts attributable to the unaffordable cost of living. Moreover, SSP will lose its originality when its old indigenous traces are removed, becoming similar to other highly developed districts.

4. Conclusion

This study aims at using Lefebvre’s spatial triad to analyse the change of economic traces in Sham Shui Po. It is found that the advent of hipsters’ stores is due to a series of factors that correlate to each other. First, the diminishing manufacturing industry provides more vacant sites for the entry of hipsters. The vacant sites further decreased the rental price in Sham Shui Po, attracting hipsters with the scarce financial power to enter. Eventually, it contributes to the present gentrification in Sham Shui Po, where traces collide frequently.

References

(1) Hong Kong Poverty situation - censtatd.gov.hk. (n.d.). Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/data/stat_report/product/B9XX0005/att/B9XX0005E2020AN20E0100.pdf.

(2) Thodelius, C. (1970, January 1). [PDF] Rethinking Injury Events. explorations in spatial aspects and situational prevention strategies: Semantic scholar. undefined. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Rethinking-Injury-Events.-Explorations-in-Spatial-Thodelius/a80c2fb348c255b1ae401c26865742ce94763f74.

(3) 讓我們從一張張舊照片起說香港的故事:東九龍. HKIPF. (n.d.). Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://hkipf.org.hk/zh/events/%E8%AE%93%E6%88%91%E5%80%91%E5%BE%9E%E4%B8%80%E5%BC%B5%E5%BC%B5%E8%88%8A%E7%85%A7%E7%89%87%E8%B5%B7%E8%AA%AA%E9%A6%99%E6%B8%AF%E7%9A%84%E6%95%85%E4%BA%8B%EF%BC%9A%E6%9D%B1%E4%B9%9D%E9%BE%8D/.

(4) 林可欣 (2017, October 26). 攝影展記難民逃港情景 越南難民的30年同行者:他們都感激香港. 香港01. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.hk01.com/%E7%A4%BE%E5%8D%80%E5%B0%88%E9%A1%8C/128151/%E6%94%9D%E5%BD%B1%E5%B1%95%E8%A8%98%E9%9B%A3%E6%B0%91%E9%80%83%E6%B8%AF%E6%83%85%E6%99%AF-%E8%B6%8A%E5%8D%97%E9%9B%A3%E6%B0%91%E7%9A%8430%E5%B9%B4%E5%90%8C%E8%A1%8C%E8%80%85-%E4%BB%96%E5%80%91%E9%83%BD%E6%84%9F%E6%BF%80%E9%A6%99%E6%B8%AF.

(5) Population and household statistics ... - censtatd.gov.hk. (n.d.). Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/data/stat_report/product/B1130301/att/B11303012020AN20B0100.pdf.

(6) What are gentrification and displacement? Urban Displacement. (2021, November 3). Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.urbandisplacement.org/about/what-are-gentrification-and-displacement/.

(7) Ng, C. F. (2021). The combination of old and new traces in SSP [Photograph].