1. Introduction

Formerly a cotton mill (Nan Fung Cotton Mills), The Mills itself is a cultural trace and an integral part of Hong Kong history for it: 1) reflects Hong Kong’s workclass culture and Hongkongers’ can-do spirit in the past; 2) witnesses Hong Kong’s first and second economic transformations. The Mills was revitalised into a design hub in 2018, which inevitably redefined some of the original traces and cultural implication of this place. In light of this, this paper will examine how the renovation has reshaped the space of The Mills from a cultural geography perspective with the aid of the Spatial Triad model proposed by Henri Lefebvre (1991).

2. Cultural Geography Perspectives in Use

Cultural geography defines a place as the conglomeration of all traces in that space, and traces are created through the intersections of geographical contexts and culture (See Figure 1). Without traces, a place would lose its identity and become a non-distinguished space. In other words, traces bestow upon a place its unique meaning.

![]()

Figure 1. Relationship between geographical contexts, culture, traces and place (Anderson, 2015)

Renovation of The Mills has transformed the geographical contexts and culture, and thus the traces, of this place. Transformation of the traces necessitate a change in the cultural landscape of The Mills. Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad will be adopted as an analytical model to examine such change. Lefebvre’s (1991) Spatial Triad entails three constituents: spatial practice, representation of space and representational space. In this report, these three constituents are conceptualised in Table 1:

Table 1: Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad Model (Lefebvre, 1991; Wang, 2009)

|

Spatial practice |

The collection of social activities happening in one place |

|

Representation of space |

Political, legal and social actions by dominating power to regulate a place |

|

Representational space |

An integration of the previous two spaces where old and new traces are present at the same time |

Lefebvre’s model is well-suited for analysing how The Mills was and is used before and after revitalisation (spatial practice); how The Mills is regulated by its dominating power (representation of space); and how traces of The Mills are preserved after the revitalisation (representational space). Collectively, the three spaces encapsulate how the cultural landscape of The Mills is transformed by its revitalisation.

3. Empirical Analysis

3.1. Representation of Space

Representation of space is defined as “conceptualized space, the space of scientists, planners, urbanists, technocratic subdividers and social engineers” (Lefebvre 1991, 38). From this we could see how the authorities adopt a system of signs and codes to organise and direct spatial relations.

3.1.1 Government as a Dominating Power

The government is a dominating power of this space by providing incentives and the framework of revitalization for developers to encourage them to transform or create new uses of the industrial buildings. For safety and reasonable space planning, the government promotes a plan for revitalization.

In 2018, Hong Kong government restarted the revitalization of industrial buildings, accepting applications from owners to modify entire industrial buildings with a building age of 15 years or more and exempting land lease waiver fees (HK Government [Gov], 2018). On the other hand, the government requires an additional condition that 10% of the floor area will be used for government-designated purposes (Gov, 2018). In the case of The Mills, a floor is used for a free exhibition which shows the cultural traces from Hong Kong's textile industry. Also, developers are required to widen the permitted uses of buffer floors to facilitate the partial conversion of industrial buildings lower than buffer floors for non-industrial uses (Gov, 2018). The 4th floor of The Mills, which was originally used as a buffer floor, has now been used as a venue for conferences and lectures.

3.1.2 Property Developer as a Dominating Power

The property developer, Nan Fung Group, is another dominating power of this space. We are able to indicate an interesting conflict of powers between the property developer and the government. Despite Nan Fung Group being legal owner of the Mills, it has to comply with the rules and regulations laid down by the government. During our site-visit, we examine how Nan Fung Group employs different soft-line measures to classify users of space. First, we notice that public parks and exhibition halls are located on the upper floors, so that visitors would have to pass by different stores before assessing these free public spaces (See Figure 2). This is a common practice to stimulate consumerism. Besides, artistic and historical elements have been integrated into the products sold in The Mills. For instance, clothing stores are stationed at the entrance of the textile exhibition, as if the products sold in these stores are given a sense of historicity, thus creating an illusion that consumers are purchasing products that embed greater and higher values, not just merely garments.

Figure 2. Route by which visitors access public space in The Mills (The Mills, n.d.)

3.2. Spatial Practice

Spatial practice “embraces production and reproduction, and the particular locations and spatial sets characteristic of each social formation” (Lefebvre 1991, 33), mediating between the conceived and the live, and keeping representations of space and representational space together, yet apart (Merrifield, 2000). Spatial practices before and after the revitalisation of The Mills are significantly different and thus will be discussed separately.

3.2.1 Spatial Practice before Revitalisation

Before the revitalisation, three users of this space were involved: the Nan Fung Group, workers of Nan Fung Cotton Mills and movie crews.

Nan Fung Group

Nan Fung Group’s founder Chen Din Hwa fled to Hong Kong due to the Chinese Civil War in the 1940s-1950s. During his stay in Hong Kong, he realized that Hong Kong has limited large, flat lands, meaning Hong Kong is well-suited for light industry like the textile industry. Due to the coincidence of these geographical contexts, Mr. Chen founded Nan Fung Cotton Mills in 1954.

Workers

Workers of Nan Fung Cotton Mills started their activities in this space after the operation of The Mills in 1956. During the 1960s-1970s, the textile industry developed rapidly. Cotton Mills reached peak production as high as 3000 million cotton per year during that time, making them the production leader of cotton in Hong Kong. However, textile industry in Hong Kong has declined after the 1970s due to economic reform in China, forcing the Cotton Mills 4,5 and 6 to shut down in 2008. Workers’ activities in this space have hence stopped.

Workers

As the textile industry declined, Cotton Mills 1,2 and 3 were vacant in the 1990s. These mills were used for filming a movie Lifeline and were demolished afterwards.

3.2.2 Spatial Practice after Revitalisation

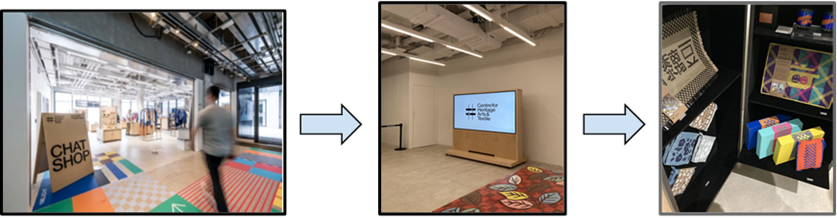

During our site-visit, we locate six major users within The Mills, including local businesses, charitable groups, local and foreign artists, shoppers with high consumption power, users of the public space and key opinion leaders (KOLs). The interactions between users are influenced by the power balance between classes. The authorities implement policies which structure the uses of space. Figure 3 indicates the relationship between users.

Figure 3. Relationships between different users of The Mills

Property Developer & Government

The property developer and the government are the dominating powers capable of constructing and redefining the meanings of space. The former aims at profit maximization but is restricted by the rules and regulations laid down by the latter. As a result, the developer has to adopt soft-line measures in order to generate more profits by engaging high-end local businesses. On the other hand, the developer still has to reserve a considerable amount of public space for charitable groups and artists. Hence, The Mills also serves as a platform for certain exhibitions and showcases.

High-end Local Businesses & Shoppers

High-end local businesses utilise tactical branding strategies of repackaging high-priced goods with an aesthetic shopping experience. Hence, shoppers with high consumption power are attracted to this place (See Figure 4), including but not limited to: holiday shoppers, one-time shoppers and tourists. Given that The Mills mainly offer high-priced goods and supply of daily necessities is limited, this group is, self-explanatorily, the product of space planning by the property developer.

Figure 4. High-end businesses and shoppers in The Mills (Source: The Mills)

Users of the Public Space

The gap created by government regulations provides space for users of the public space. This could include citizens from all walks of life, they take advantage of the free service and space in The Mills without having to spend or consume (See Figure 5). In practice, there is only a limited flow of shoppers with high consumption power, most of the visitors are users of the public space. As a result, most businesses in The Mills close early to reduce costs. This phenomenon reflects the findings of Michel de Certeau in The Practice of Everyday Life, where he notes that when there is an absence or a gap of authoritative power, the weaker groups could utilise the previously defined space and transfer it into their own space.

Figure 5. Users of the public space in The Mills (Source: Site-visit)

Key Opinion Leaders & Media

The last group of users encapsulates the artistic side of The Mills as well as its commercial practice, they are the key opinion leaders (KOLs), or the media in general. They are actively advancing a consumerist culture, such as promoting cool shopping spots or instagrammable cafes in The Mills. Its historical background is only a superficial coat used to stimulate consumer spending.

3.3. Representational Space

However, Sessions 1 and 2.2 have revealed that The Mills currently is not only purposed for production. It is positioned as a space for conservation by the government, and a space for commerce and consumerism by the developers, businesses and shoppers. This session will cover how The Mills preserves old and acquires new traces and how these traces give rise to the multi-purpose nature of The Mills.

3.3.1 The Mills as a Space for Production

The Mills preserve one of its most important traces – textile production – by organising regular creative workshops where participants can make their own textile products.

Interestingly, The Mills acquired new traces relevant to production after its revitalisation. The rooftop of the building features a planting zone for agricultural purposes and artistic creation. There are also designated zones for entrepreneurs to share ideas (The Mills, n.d.).

From these creative activities, it is observed that The Mills retains its production purpose after revitalisation, but the scope of production is no longer limited to textile products.

3.3.2 The Mills as a Space for Production

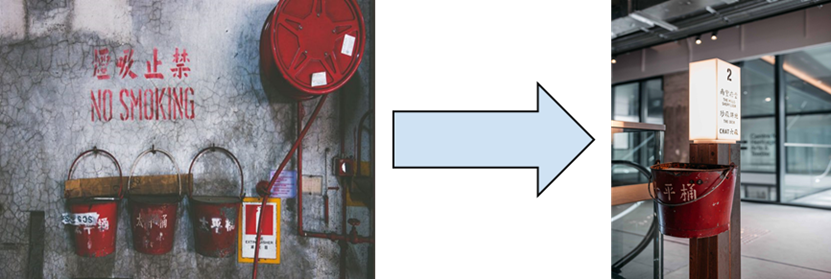

To conserve historicity of the place, the developers attempted to transform tangible traces of Nan Fung Cotton Mills by endowing them new uses. Such traces witness the evolution of The Mills and give us a glimpse in how it looked before revitalisation.

A case in point is the sand buckets. Firefighting system and equipment was limited back in the days. Hence, sand buckets were used to extinguish fire. After revitalisation, sand buckets are now hung on direction signs, welcoming visitors and reminding them of the history of this place (See Figure 6). From this example, it can be observed that traces could never be decontextualised from the geographical context they are in. Despite being as physically intact as it was prior to the revitalisation of The Mills, the sand bucket is now endowed with a purpose (welcoming visitors) different than before (putting out fire).

Figure 6. Transformation of the sand bucket (Source: The Mills)

With that said, transformed traces may not necessarily accurately represent The Mills before its revitalisation. We observe that numerous fashion brands open business in The Mills. Such traces are largely capitalistic and consumerist by nature, the polar opposite to the working-class culture that Nan Fung Cotton Mills used to represent.

As aforementioned, a place is defined as the conglomeration of traces in that space. As the traces in The Mills are transformed, its space must have been endowed with a new purpose accordingly. The rise of fashion brands in The Mills indicates its transition from a space for production to a space for consumerism and commerce.

3.3.3 The Mills as a Space for Consumerism and Commerce

As previously mentioned in Session 2.2, The Mills usually feature high-end businesses targeted at shoppers with high purchasing power. Such use of space is incongruent with the workclass culture Nan Fung Cotton Mills used to represent and contradicts with the conservation purpose of The Mills. This calls back to Session 2.2 again where different users of the space tried to struggle for seizing the control of The Mills and transforming it to their favor with their actions. The struggle among these parties ultimately precipitates the multi-faceted yet contradictory nature of The Mills: it is simultaneously a space for conservation and commerce.

3.3.4 The Mills as a Trace of Hong Kong

Nan Fung Cotton Mills can be seen as a trace of Hong Kong as it embodied workclass culture and the development of Hong Kong’s textile industry. After revitalisation, The Mills remained a trace of Hong Kong. However, it is no longer localised to represent the development of Hong Kong’s textile industry only. The Mills’ transition from a space for production to a space for consumerism and commerce comes with two implications: 1) it embodies Hong Kong’s transition from being secondary-sector-heavy to tertiary-sector-heavy; 2) it witnesses women empowerment in Hong Kong (i.e. main female users of the space change from workers to consumers).

Conclusion

This paper examines how the cultural landscape of The Mills is transformed with its traces. Despite the developer’s attempt at preserving traces of Nan Fung Cotton Mills, they may not accurately represent the cultural landscape of the place before revitalisation faithfully. The Mills also acquired new traces as a result of different parties struggling to dominate its space. The combination of new and old traces collectively bestowed upon The Mills production, conservation and commercial purposes.

References

Anderfson, J. (2015) Understanding cultural geography: places and traces (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Hong Kong Government. (2018, October 10). The Chief Executive’s 2018 Policy Address. https://www.policyaddress.gov.hk/2018/chi/pdf/PA2018.pdf

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The Production of Space (Vol.142). Blackwell: Oxford.

Merrifield, A. (2000). Henri Lefebvre: A socialist in space. In M. Crange & N. Thrift (Eds.), Thinking space (pp. 167–182). London, England: Routledge.

The Mills (n.d.). CHAT Shop. https://www.themills.com.hk/en/shopfloor-shop/chat-shop/

The Mills. (n.d.) Green Ladies & Green Little. https://www.themills.com.hk/en/shopfloor-shop/green-ladies-green-little/

The Mills. (n.d.) Introduction of Fabrica. https://www.themills.com.hk/en/fabrica/introduction/

The Mills. (n.d.) Revitalization & Heritage. https://www.themills.com.hk/en/about-the-mills/heritage/

王志弘(2009)。多重的辯證列斐伏爾空間生產概念三元組演繹與引申。地理學報,(55),1-24。doi:10.6161/jgs.2009.55.01