From a cultural geographical perspective, why and how have the traces in the Kowloon Walled City been preserved and altered?

Figure 1. Front Door of the Kowloon Walled City Park (Site Visit)

Introduction

The Kowloon Walled City (the Walled City) was once a fort constructed by the Qing government at the tip of Kowloon Peninsula, for protection against the British army situated on Hong Kong Island. However, disputes abounded over the sovereignty of the Walled City between the Chinese and British government since the late 19th century.

Amid the conflicts, the Walled City was gradually abandoned, without an obvious controlling power. Right after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the influx of immigrants to the city led to a rise of illegal structures and businesses. Myriads of cultural traces were constructed, some of which exist while others have become part of the history. This project aims to scrutinize how different traces were formed in the Walled City over the course of time.

Throughout this study, photos taken before the Walled City’s demolition and multiple graphs are utilized to visualize events, traces, values and conflicts in the Walled City vividly.

Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

To reveal the reasons for the changes of cultural landscape in the Walled City, the perspectives of cultural geography listed below are used for analysis.

Traces and Tracemakers

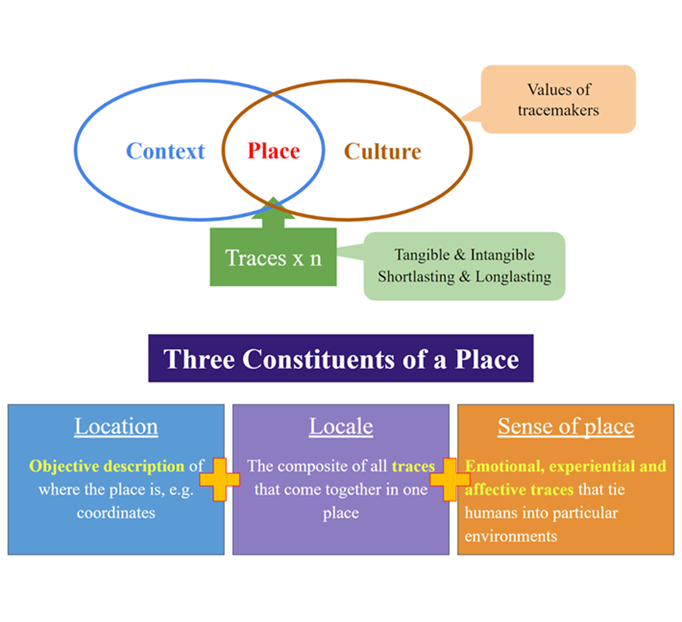

Traces are marks or remnants left in a place by cultural life. Traces can be tangible (e.g. buildings, signs and statues) or intangible (e.g. activities, performances, emotions). “Tracemakers” are those who create traces (Anderson, 2015). Traces exist in places, and are usually intentionally created to convey the values of tracemakers . On the other hand, places are constituted by “location”, “locale” and “sense of place” (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The concept of ‘place’

Therefore, space is different from place. Spaces are empty abstractions (Lefebver, 1991) which are often scientific, open and detached (Anderson, 2015), while places are drenched in cultural meaning (Preston, 2003) which are often intimate, peopled and emotive (Anderson, 2015).

Power

Power is a transformative capacity, the ability to transform the traces of others to achieve certain strategic goals (Cresswell, 2000). A dominating power controls or coerces others’ actions whereas a resisting power challenges the dominating power usually through demonstrations by questioning ‘who is in control of culture and power’ (Anderson, 2015). The interactions between powers and stakeholders are essential in understanding the formulation of the conceived space of the Kowloon Walled City Park and subsequent implementation of the plan.

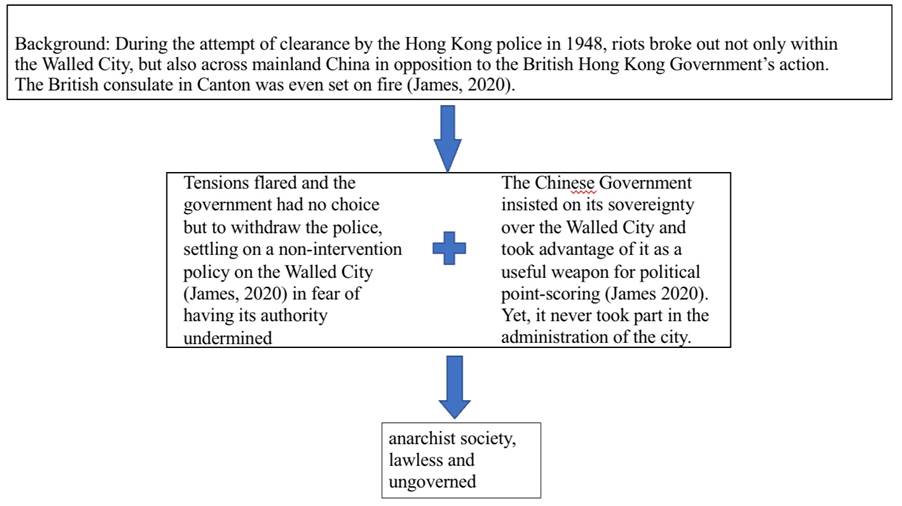

Anarchic state

Anarchy is a situation in a country in which there is no government, order or control (Oxford, 2021). There had been an anarchic state in the Walled City since the 1950s, during which no dominating power was present. The chart below (Figure 3) analyses the formation of the anarchist society, which contributed to formation of representation of space (to be discussed later).

Figure 3. Formation of anarchist society.

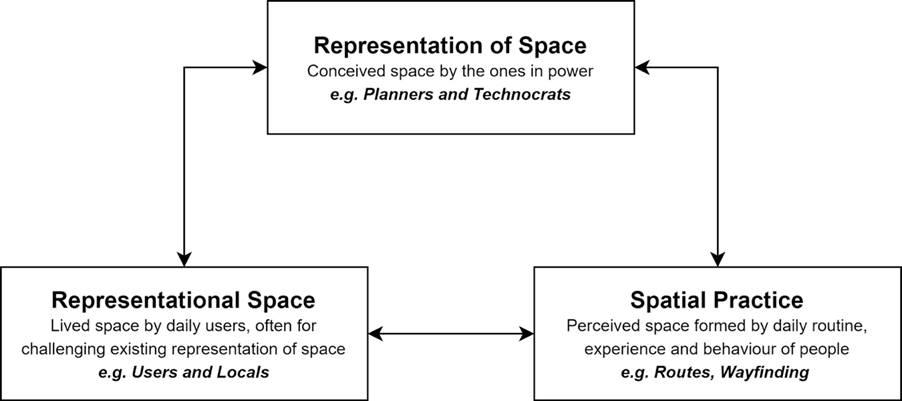

Spatial Triad

French Marxist theorist Henry Lefebvre introduced the spatial triad in his book, "The Production of Space”, that space is produced by the interaction of the three elements: spatial practice, representation of space and representational space (Lefebvre, 1991).

The theory helps construct the timeline of events happening in Walled City (see its graphical representation in Figure 4). It is helps clearly delineate the change of “locale” and “sense of place”, thus transformation of traces of the Walled City as a place of the same physical location over time.

We start with “spatial practice”, explaining the old traces like the prominence of the prostitution, gambling and drug industries and the Yamen in the case of the Walled City that reflect the “locale” and “sense of place” at its original site, then “representation of space”, identifying powers of the Walled City and how they interacted to formulate the conceived space of the Kowloon Walled City Park Plan altering “locale” and “the sense of place”, and finally “representational space”, introducing the traces preserved in the plan as well as how new traces have been formed, creating new “locale” and “sense of place”.

Figure 4. The Spatial Triads. (CUHK Geography and Resource Management, 2020)

Spatial Practice - Perceived Space

Tangible and intangible traces that represent the perceived space of the Walled City are discussed below.

Political Perspective:

Beginning from the 1950s, the Walled City was in an anarchic state, giving rise to the following phenomena:

Unlicensed Practice of Medical Services Providers and Food Factories Operators

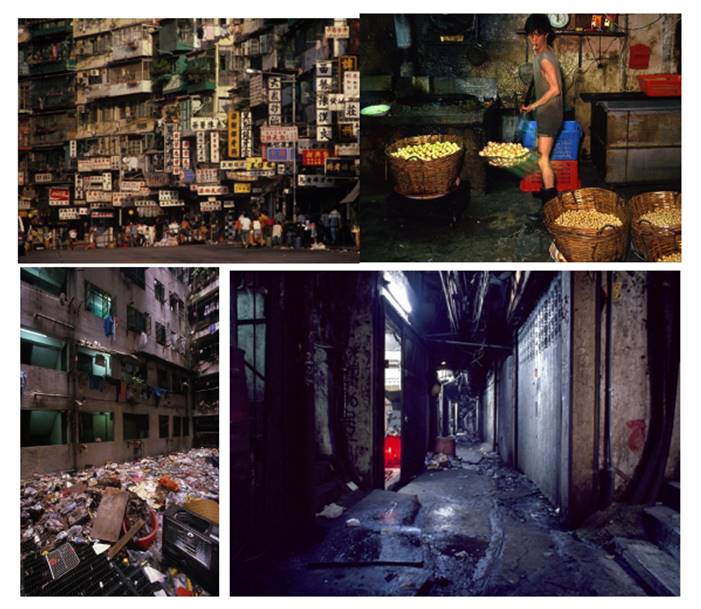

After WWII, immigrants from Southeast Asia and China rushed into the Walled City. Numerous professionals like doctors and dentists and food factory operators set up businesses there without the need to obtain a license from the Colonial Government. They left behind tangible traces: a sprawl of doctors’ or dentists’ advertisement signs, and food factories which could exist in close proximity to residential flats (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Street View of the Kowloon Walled City. (Girard, 1993)

Living Environment

Two related tangible traces were left by the anarchic state. First, the anarchic state led to disorganized management of the city, where residents discarded refuse to the streets arbitrarily and no organized cleaning up was exercised by the bureaus, resulting in poor hygiene (Figure 5). Second, architectural constructions were unplanned, creating a dimly lit living space (Figure 5). Therefore, the Walled City was also called the City of Darkness.

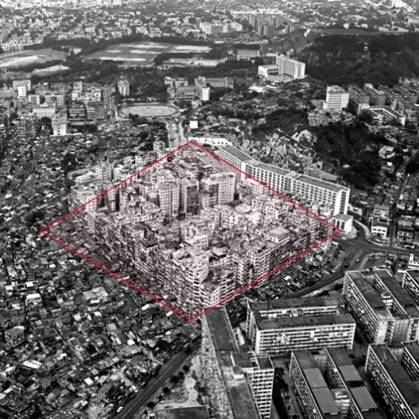

Figure 6. The claustrophobic compounds (enclosed in the red square) in the Walled City had a dreadful population density of 1,255,000 inhabitants/ km2 (Wikipedia, 2021), which was by then the world’s highest. In comparison, Macau, where the population density is now the globe’s highest, only has 21,340 inhabitants/ km2 (Wikipedia, 2021).

Prominence of the Prostitution, Gambling and Drug Industry

Associated with the anarchic state, most law enforcers would not bother to step into the Walled City. Hence, tangible traces of prostitution, gambling and drugs were the leading entertainment industries back in the 1950s. For instance, the place that invented the first stripdance in Hong Kong attracted many residents to watch the show. Furthermore, the drug industry flourished especially in Kwong Ming Street, where numerous drug retailers sold heroin to the drug addicts.

Social Perspective:

Yamen

This is a tangible trace of the Walled City. Once a military office of the Qing army, the Yamen was left by the Qing government in 1899 when the army departed the Walled City. In the 1960s, China Native Evangelistic Crusade rented the Yamen and used it as a clinic, church and school with free education. In 1978, the building was turned into an elderly centre which functioned until the demolition in the 1990s. The Yamen provided a place for socialization which fostered residents’ sense of belonging.

Community Relationship

Rampant crimes and scarce resources created a need for community self-help in order to survive (Lam, 2016). Trust thus developed between residents resulting in a harmonious community with strong bonding, an intangible trace of the Walled City.

Most of the above traces were destroyed in the demolition and only some are preserved (to be discussed later).

Representation of Space - Conceived Space

Cultural order and geographical border

Traces culturally order places (Anderson, 2015). People in places are inclined to defend their cultural traces. In our study, the residents of the Walled City defended their homes, whilst the Colonial Government attempted to demolish the enclave, in an attempt to restore law and order in the Walled City, bringing about conflicts between different powers.

Dominating powers

Dominating powers should be first identified before discussion of their conflicts. We identified the Qing Government and the Colonial Government at different periods creating different traces above. The state of anarchy will be further elaborated below as well in terms of its role in shaping traces in the Walled City.

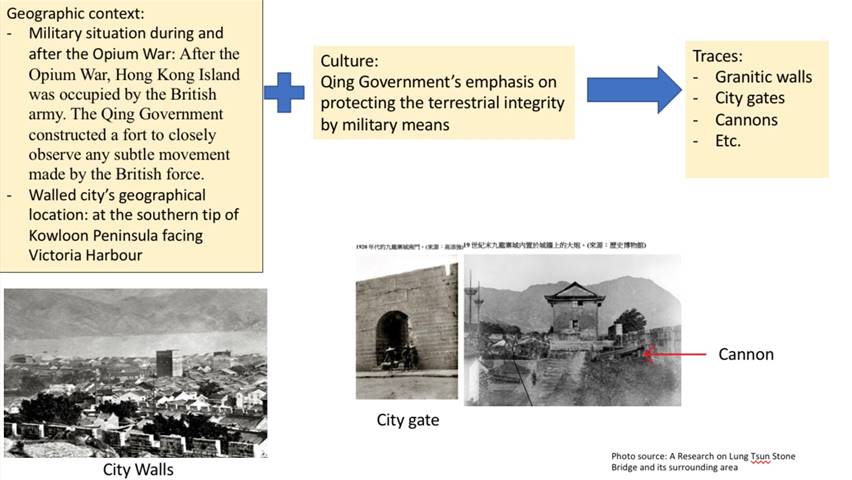

Qing Government

The power that directly influenced the construction of Walled city and its traces through military planning in 1847, as summarized in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Formation of traces under Qing Government as dominating power.

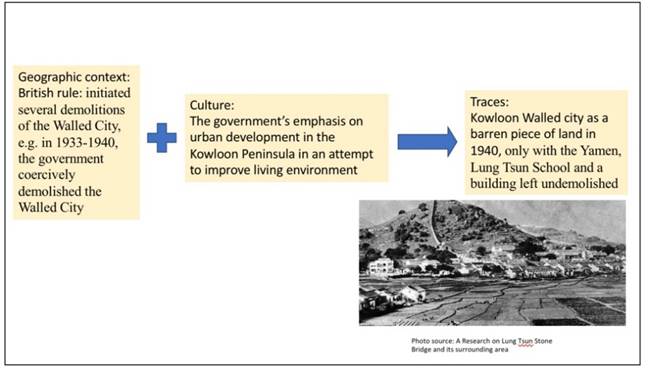

Colonial Government

The power involved in the intentional destruction and unintentional conservation of some very few cultural traces through coercion, as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Formation of traces under Colonial Government as dominating power

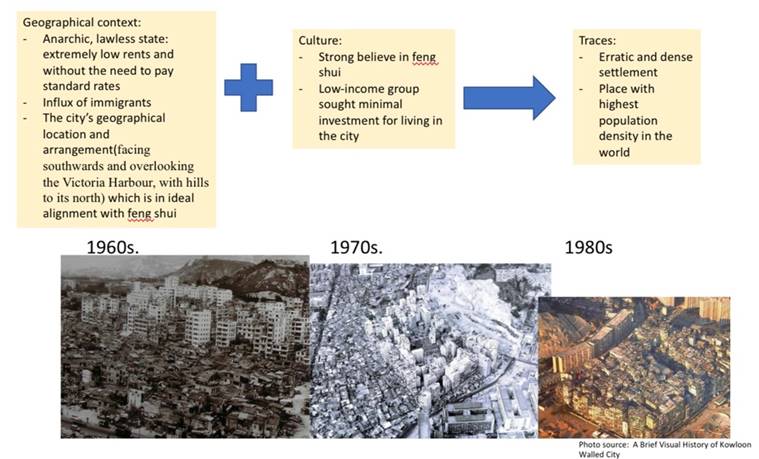

Anarchic state (三不管)

Immigrants swarmed into the Walled City in the 1950s, enticed by the perfect alignment with feng shui and the extremely low cost of moving in. People started to construct illegal structures, open up businesses, and develop an unordered community, morphing it into an area packed with notoriously tall and erratic structures (Figure 9). This was one of the reasons for demolition.

Figure 9. Formation of traces in the anarchist society

Plan for demolition and park development: interaction between powers and serious urban decay

Although previous attempts to demolish the Walled City by the Colonial Government failed due to resistance from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and residents of the Walled City, the attempt in 1987 succeeded. Reasons are explained below.

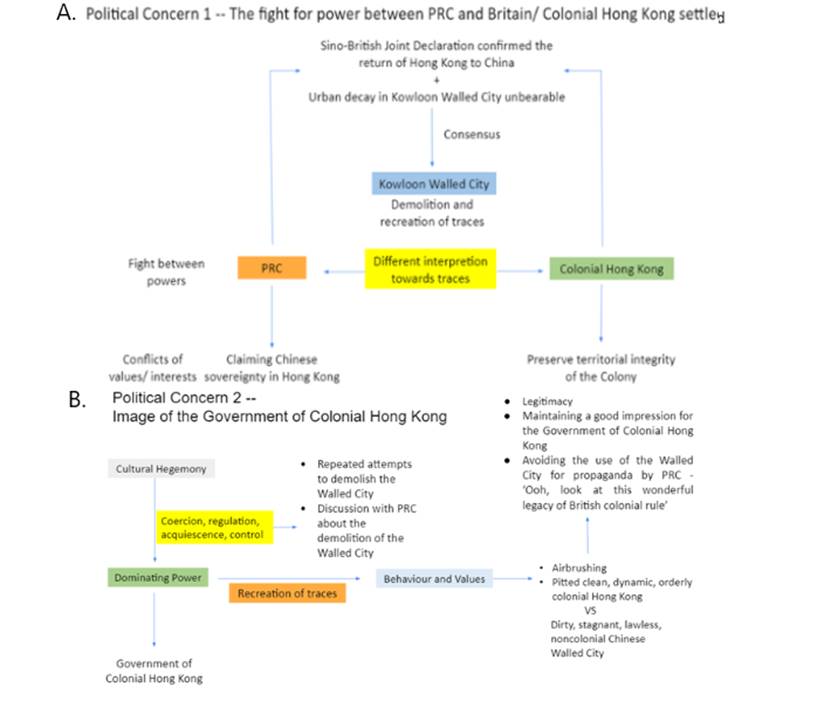

The resolution of HK’s sovereignty, the crux of all disputes, by the Sino-British Joint Declaration in 1984 ensured HK’s return to China in 1997. There was no need for the PRC to maintain the Walled City as a historical claim for sovereignty in HK. Therefore, when the plan to demolish and convert it into a park was proposed in 1987, both the PRC and Britain agreed with it. This is represented in Figure 10A.

Meanwhile, the Colonial Government used the plan to show a clean and orderly colonial HK, to prevent the PRC from criticizing them as incompetent for not tackling the poor living environments of the Walled City, thereby preserving the image of the colonial government (Fraser & Li, 2017), as indicated in Figure 10B. The park was therefore planned as a Qing-styled garden. Purposeful preservation of the old trace, the Yamen, by the dominating power was planned, as it is in accordance to the Qing-styled design of the park and the value the Colonial Government would like to convey.

The disturbing urban decay issues, as previously described, also represented a pressing need to improve residents’ living standards.

Figure 10A &B. Summaries of the political factors influencing the demolition plan.

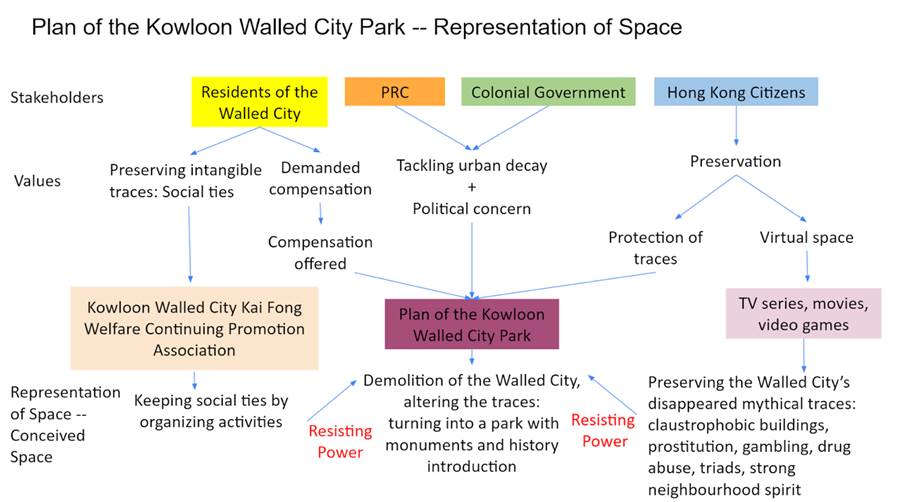

The solution to the above problems is the imagination of the Kowloon Walled City Park as a recreational area. Different stakeholders and powers interacted to form the conceived space of the park plan, which incorporated values from residents of the Walled City and the general public, including compensation and resettlement for the prior and preservation for the latter.

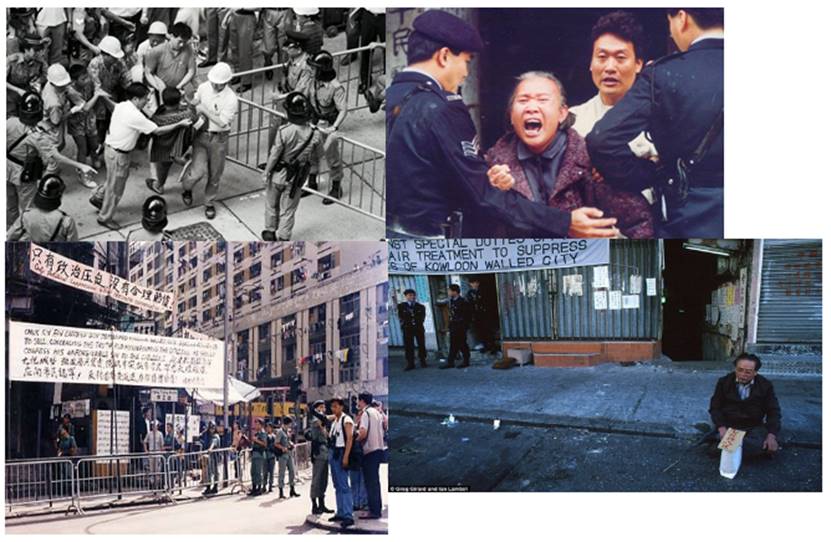

However, the cultural landscape would be completely altered by the plan. Resisting powers who exercise their transformative power therefore arose. Some residents formed the Kowloon Walled City Kai Fong Welfare Continuing Promotion Association to preserve the neighbourhood spirit lost in the demolition, while others rallied against the act of demolition (Figure 11), which were suppressed by the Colonial Government as the dominating power. Some constructed their spatial imagination of the Walled City at virtual spaces like TV series, movies and video games (to be discussed later). See Figure 12 for the summary of interaction between stakeholders: the residents, the Colonial Government, the PRC and the general public.

Figure 11. Residents rallied against the demolition plans. (Grundy, 2013)

Figure 12. Illustration of how different stakeholders interact to form the Walled City Park plan and the creation of other conceived spaces that are different from the hegemony.

Representational Space - Physical Space

After the Walled City was torn down in 1994, the site was reconstructed into the Kowloon Walled City Park, which was the result of compromission and interaction of the stakeholders as discussed previously. This gave the existing physical space new functions of:

l City lung

l Recreational land use

l Preservation of cultural relics

Here, preservation refers to the process of retaining a place’s cultural significance by maintaining its existing fabric and retarding deterioration (Australia ICOMOS, 1999).

Yamen

Located at the centre of the park, the Yamen, one of the park’s declared monuments, is the only building that has been fully preserved and restored to its original appearance.

The Yamen retains traditional Qing architectural features, with walls built from brick and granite and tile-covered roofs (Figure 13). Also, the artefacts are tangible traces that reflect the building’s history as a Qing military office. These artefacts include ancient cannons and calligraphy written by a Qing deputy general (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Tangible traces in the Yamen (Site Visit).

Old South Gate

Two granite plaques engraved with the Chinese characters “South Gate” and “Kowloon Walled City” were unearthed at the site of the original South Gate during the demolition of the Walled City, and is now being displayed at the park (Figure 14). Moreover, a building’s cornerstones made from reinforced concrete are displayed at the park, preserving part of the architectural features from the anarchic times (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Top: Granite plaques unearthed at the original site of the South Gate, which were buried by residents of the Walled City during WWII to prevent the invading Japanese army destroying them (Wikimapia, 2021).

Bottom: Cornerstones of a building (AIA Vitality Park, 2021)

Representational Space - Virtual Space

Despite the preservation of characteristic tangible traces from the Qing Dynasty, many traces that once existed in the anarchic times have disappeared from the physical space during demolition. These tangible and intangible traces, like the cramped living environment, ways of life of residents and their social bonding, cannot be fully represented by images and text descriptions in the park exhibition areas alone. Hence, these traces are converted into cultural memory and continue to exist in our lived space in the form of virtual concepts and stories.

In the entertainment industry, numerous movies, TV shows, video games and animations have their plots set in the Walled City, with particular emphasis on the mysterious and legendary features of the Walled City, like the claustrophobic buildings and triad activities (Anderson, 2015).

Furthermore, architectural styles that matured in the development of the Walled City, namely vertical development, parasitic constructions and multifunctional buildings are also seen in modern architecture in HK, such as skyscrapers and unauthorised constructions.

The figure below is an illustration of the cross-section of the Walled City drawn by Japanese researchers, showing detailed layouts of the residential, commercial and industrial areas in the city, thus the livelihoods of residents who once lived there.

Conclusion

In this study, the spatial triad is applied to the analysis of the changing landscapes of the Walled City. As the Walled City evolved from a military station to an anarchic city, numerous traces were created in the perceived space. However, the emergence of new social and political practices brought about clashes of values and interests, which consequently induced actions from dominating powers to formulate and execute plans to demolish the Walled City and construct a park representing the ideals of their conceived space. The end product of the interaction of powers is a physical space which provides aesthetic recreation while preserving part of the city’s history in our lived space. The remaining cultural memories are embodied in various forms of artistic creations, enabling continuous appreciation of cultural uniqueness of the Kowloon Walled City.

References

Anderson, J. (2015). Understanding cultural geography: Places and traces (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Antiquities and Monuments Office. (2021). Former yamen building of Kowloon walled city, Kowloon Walled City Park - Declared monuments - Antiquities and monuments office.

https://www.amo.gov.hk/en/monuments_63.php

AUSTRALIA ICOSMOS (1999). Charter (the Burra Charter) for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Significance.

https://www.gdrc.org/heritage/icomos-au.html

Crawford, J. (2020, Jan 6). The Strange Saga of Kowloon Walled City. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/kowloon-walled-city

Chung, P. Y. & Ko, T. K. (2012, Dec). A Research on Lung Tsun Stone Bridge and its surrounding area.

Fraser, A. & Li, E.C.Y. (2017). The second life of Kowloon Walled City: Crime, media and cultural memory. Crime Media Culture, 13(2), 217-234.

Grudy, T. (2013, Apr 7). HISTORY – A Brief Visual History of Kowloon Walled City. http://hongwrong.com/kowloon-walled-city-photos/

Lam, S. (2 December 2016). Here’s What Western Accounts of the Kowloon Walled City Don’t Tell You. ArchDaily. Retrieved 8 November 2021, from:

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Oxford: Blackwell.

Oxford University Press. (2021). Anarchy. Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 9 November, 2021, from:

https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/7118?redirectedFrom=anarchy#eid

Preston, C. (2003). Grounding Knowledge: Environmental Philosophy, Epistemology, and Place. University of Georgia Press: Athens and London.

陳芷慧. (2016, August 28). 【真城寨英雄】揭牙佬身世之謎 城寨逾百無牌牙醫 街症嚴重不足. 香港01. https://www.hk01.com/%E7%A4%BE%E5%8D%80%E5%B0%88%E9%A1%8C/39683/%E7%9C%9F%E5%9F%8E%E5%AF%A8%E8%8B%B1%E9%9B%84-%E6%8F%AD%E7%89%99%E4%BD%AC%E8%BA%AB%E4%B8%96%E4%B9%8B%E8%AC%8E-%E5%9F%8E%E5%AF%A8%E9%80%BE%E7%99%BE%E7%84%A1%E7%89%8C%E7%89%99%E9%86%AB-%E8%A1%97%E7%97%87%E5%9A%B4%E9%87%8D%E4%B8%8D%E8%B6%B3

香港房屋協會. (2016, September 9). 寨城的黑色歲月(下) - 房協長者通.

https://www.hkhselderly.com/tc/travel/scenic/275

彭麗芳 (2019, March 5). 【閱讀清單】從九龍城寨看香港建築發展. 明周文化. Retrieved November 8, 2021, from https://www.mpweekly.com/culture/%E4%B9%9D%E9%BE%8D%E5%9F%8E%E5%AF%A8-%E5%BB%BA%E7%AF%89-%E6%9B%B8-41866.

頭條日報. (n.d.). 靈感國度--九龍城寨 的空間意義. 頭條日報 Headline Daily. Retrieved November 8, 2021, from https://hd.stheadline.com/news/columns/28/20150727/356798/%E5%B0%88%E6%AC%84-%E9%9D%88%E6%84%9F%E5%9C%8B%E5%BA%A6-%E4%B9%9D%E9%BE%8D%E5%9F%8E%E5%AF%A8-%E7%9A%84%E7%A9%BA%E9%96%93%E6%84%8F%E7%BE%A9.

Images:

Girard, G. (1993). City of Darkness: Life in Kowloon Walled City. Retrieved 8 November 2021, from:

http://www.greggirard.com/work/kowloon-walled-city--13