A Study of the Conservation Value of Walled Villages in Hong Kong

Foreword

Hong Kong has a high population density, but due to its hilly geographical landscape, there has been a limited supply of flat land for housing, which causes serious housing problems. Since 1982, a developer named Cheung Kong Holdings has acquired the walled village Nga Tsin Wai Tsuen, and knocked down many centennial houses for redevelopment, in hopes of supplying 750 private apartments after the scheme was launched. Such actions of the developer have aroused much controversy between the conservation of walled villages and urban development. “They never listen to us! I don’t want money and I don’t want to leave, on the day they demolish here, I will lock myself in my shop!” said Mr. Lin, who had been selling clothing and electronics in Nga Tsin Wai Tsuen for ten years (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mr. Lin who worked in in Nga Tsin Wai Tsuen for ten years (Photo by Lam Hei Yu)

Introduction

Walled villages are one of the oldest local cultures in Hong Kong and are commonly found in the New Territories. These villages can be divided into two categories, namely Hakka and Punti. There are a variety of cultural traces that can only be found in walled villages, including unique meals and wall designs, and they emerged mainly because of different cultural geographical factors. However, many walled villages are confronted with the risk of being demolished due to rapid urbanization. While developers have continuously attempted to reconstruct walled villages for the city's development, local villagers and citizens have opposed such measures in order to prevent the loss of the villages’ cultures. Therefore, through the use of Henri Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad, this project explores the cultural conflicts between conservation and urban development, which ultimately examines the conservation value of walled villages.

Cultural Geographical Perspective on Hong Kong’s Walled Villages

Traces in Walled Villages are historically rooted. During the Ming Dynasty, there were frequent pirate attacks in coastal area near South China Sea and the Pacific Ocean (Gao, 2018). Hence, local residents decided to build high walls around their villages, in an attempt to drive away the pirate’s attacks. Such defence awareness resulted in a “culture of fear”, which is distinctive to people living in the walled villages. Features showing the “culture of fear” can still be observed nowadays in the villages, such as doors with iron chains, narrow allies, and cannons.

Theoretical approach: Henri Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad

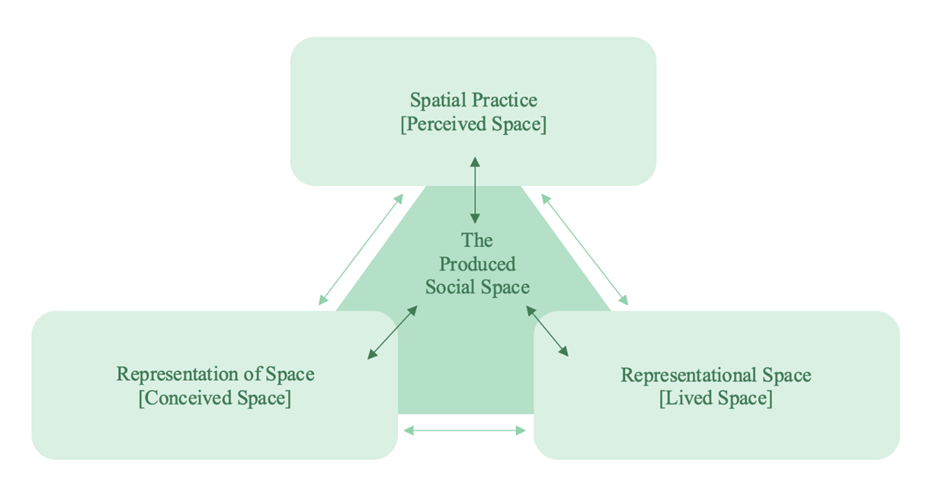

Using the theory of Spatial Triad from Henri Lefebvre’s La production de l’espace, this project explores the three elements of spatial triad and how they relate and interact with the cultural traces and geographical context of Hong Kong’s walled villages.

The three elements of spatial triad are as shown below (also see Figure 2):

l Spatial Practice – the daily usage of physical space, daily routine, experience, and behaviors of people

l Representations of Space – How space is conceived by the ones in authority, in other words, their usage and arrangement of space

l Representational Space – How people use and live within space despite the legislations devised by the authority

Figure 2. Illustration of Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad (Source: Lefebvre, 1991)

To apply the theory of spatial triad to the usage of space in Hong Kong’s walled villages, “Spatial Practice” represents the daily usage of the physical space of walled villages and the living habits, daily experience, and behaviors of residents. This can be shown through the cultural traces of residents, such as the distinctive designs of walls and the local culture – Poon Choi. In addition, “representation of space” can be interpreted as how space within Hong Kong’s walled villages is conceived by the ones in power, specifically the government who is in charge of implementing policies regarding the usage and arrangement of space. Finally, “representational space” refers to the actual living style of residents in the villages and their usage of space in spite of any laws and regulations enacted by the government.

Empirical Analysis

Conservation Values of Walled Villages

As evidenced by the demolition of Nga Tsin Wai Tsuen, certain developers wish to reconstruct walled villages which naturally brings about the loss of their cultural traces (see Foreword and Figure 1). Nonetheless, many citizens along with the government treasure the uniqueness of those traces, and thus support the conservation of the villages to protect important local cultures in Hong Kong.

Traces of walled villages are unique and difficult to recreate, such that reconstructing the villages may cause irretrievable loss of local cultures. Those traces are an amalgamation of the history and cultures of Hong Kong, which take up a large part of the collective memory of local citizens. In this regard, the preservation of those cultures can enhance people's sense of belonging and self-identity. Moreover, the distinct cultures of the walled villages can attract tourists around the globe, bringing economic benefits to local villagers and the government. This not only encourages the residents to protect the cultures of their villages, but also enables the government to receive a stable income for future conservations.

In relation to the application of Lefebvre’s Spatial triad to cultural traces of walled villages, Poon Choi Festival meal and the sharing of roasted pork are examples of traces used to examine spatial practice in the villages, as they are still largely well conserved today. Both Poon Choi Festival meal and sharing of roasted pork convey important connotations. The preparation, ingredients, setting and arrangement of a Poon Choi meal demonstrate unity and equity through the expression of gratitude within the local community. Meanwhile, the sharing of roasted pork symbolizes equality and the blessings passed down from ancestors to current villagers. The observation of spatial practice can also be explained by the “culture of fear” in walled villages. The fear of losing cultural heritage due to globalization and commercialization results in such ongoing traces to be passed on from generations to generations, thereby ensuring that all villagers share a common sense of belonging.

Furthermore, the representations of space in walled villages are shaped by the government’s authority to implement relevant laws and policies. This is evident in the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance, which guarantees that the lives of villagers are to remain unaffected (Department of Justice of the Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, 1976). As a result, this assures that physical traces like architectures and structural designs as well as non-physical traces such as beliefs and values of the locals, can be protected and preserved in walled villages.

Finally, one can understand representational space of walled villages by integrating spatial practice with representations of space. Nowadays, the concept of urbanization has penetrated the lifestyle of numerous local villagers, which has caused them to move out of their villages and seek job opportunities. Many of them prioritize a higher living standard over the conservation of walled villages. Regardless, families that moved out would still revisit their villages on special occasions. Therefore, even though there is a declining conservation awareness amongst local villagers, they still value the unique cultural traces of walled villages in the presence of globalization and cultural conflicts.

Conclusion

This investigation incorporates Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad to illustrate the various use of space in walled villages in Hong Kong, as well as to reflect the significance of their traces from a cultural geographical perspective. For instance, spatial practice can be seen in the unique wall designs and Poon Choi meals, both of which showcase the “culture of fear”. Additionally, representations of space are exemplified by the government’s imposition of laws and policies on walled villages, including the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance. Subsequently, more and more local villagers began accepting and engaging in urbanization, while their desire to revisit walled villages from time to time serves as a phenomenon that exhibits representational space. As such, despite conflicts between multiple stakeholders specifically local citizens and developers, it is found that walled villages possess its own unique conservation value. By implementing policies which aim to conserve walled villages based on the public’s request, and focus on reconstructing areas in very decrepit conditions, one can strike a balance between conservation and urban development for the preservation of cultural traces and the spatial triad in the modern world.

Reference

Department of Justice of the Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. (1976, January 1). Cap. 53 Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance. Hong Kong e-Legislation. https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap53.

Gao, X. P. (2018, March 30). 香港圍村:現代都會中的古樸民俗 [Hong Kong Walled Village: Traditions and Folklore in Modern City]. Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in Guangdong. https://www.gdeto.gov.hk/filemanager/content/pdf/publication/20180330_tc.pdf.

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Oxford: Blackwell.

Oriental Press Group. (2021, March 10). 裕民坊重建老商戶拒遷 揚言清場當日鐵鏈鎖身守舖 [Merchant Refused to Move Out prior Reconstruction of Yu Man Square, Locking Himself inside His Shop]. on.cc東網. https://hk.on.cc/hk/bkn/cnt/news/20210310/bkn-20210310161423480-0310_00822_001.html.