Temple Street has perennially been known for its myriad of cultural traces, ranging from the plethora of ancient Chinese temples, to the night-time underworld crime during the colonial times – a theme which has been portrayed in many local dramas representing low to middle-class life stories back then. From our onsite investigation, we observed that time seems to play an important role in separating the functionality of the street, and how the reputation of the street is imbued with a socially undesirable/taboo element with the transformation from day to night. While daytime belongs to worship activities and represents the integration of multiple ethnicities seen through diverse food culture among restaurants, night-time witnesses a change in the street’s function into a bustling night market as well as a red-light district and hotbed of triad crimes. The diverse traces of religion, history, ethnicity, capitalism and food culture etc., encompassing both material and non-material, have invited us to question how all these traces contribute to the cultural place-making of Temple Street, as well as to investigate the role of time (separating day and night) in creating boundaries in terms of the functionality and cultural meaning of the place.

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

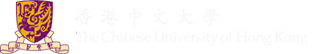

The three elements of place (Figure 1), as stated by political geographer John Agnew, includes “place as location, place as locale, and the sense of place.” (Lee et al., 2014) Location is defined as a position in the space, which can be described by longitude and latitude. Locale refers to the settings and environment of daily life actions, practices and social relations. It involves the concept where all cultural traces in the place came together as a whole. Sense of place is a subjective tie that links humans to a culture and environment. It gives humans identity while providing individual and collective meaning to a place. As place are saturated with cultural meanings, its traces are not fixed but dynamic entities as culture alters with social trend.

Figure 1: Three elements of place

(source: https://bit.ly/2Vstqu0)

Under the influx of foreign culture (Figure 2), transgression (breaching of a foreign culture into a certain region)may result when cultural orthodoxy is threatened. Notwithstanding, in inclusive regions such as Temple street, foreign cultures are acquiesced when local culture does not possess dominating power, thereby obviating cultural hegemony (domination of a specific culture in a culturally diverse society by ruling out other cultures with stronger economic or political power and influence). Given the robust foundation of local culture (Figure 3), foreign culture does not carry an eliminative potential, allowing an atmosphere of cultural inclusion to be achieved.

Figure 2: Nepal Restaurant

(Source: taken during Site Visit)

Figure 3: Herbal Tea Shop

(Source: taken during Site Visit)

3. Empirical Analysis

Figure 4: Guanyin Temple

(Source: taken during Site Visit)

In our project, we analysed Temple Street’s history when exploring how the street emerged as a place with such a special culture. In the 1870s, Temple Street got its name due to the recently built Tin Hau Temple (Figure 4) in the area. While Temple Street at that time merely served as a religious centre and was completely different from today’s Temple Street, it got its location at that time, which is the first fundamental aspect of place. Then, residents nearby started to use the space at Temple Street as a recreational area of play and rest during the 1920s. Businessmen utilized this opportunity to set up grocery stores in the street. These activities made up the locale of the street and became the prototype of today’s Temple Street. With the street becoming more famous and prosperous in the middle and late 20th century, residents became aware and proud of Temple Street’s culture. This gives the street’s sense of place and completes Temple Street’s three elements of place.

Day

The role of religion in Chinese culture is two-fold, namely the worshiping of ancestors and socialization (instructions on how to behave in the social setting). This is seen in how Tin Hau Temple shaped the habit of Yau Ma Tei (where Temple Street is located) fishermen who sought a sense of security through worshiping Tin Hau. With time, temples in Yau Ma Tei have transformed into tourist spots as they no longer reflect most residents’ lifestyles, thereby exhibiting a diminished cultural trace.

Figure 5: Mandala Arts Trading Company

(Source: taken during Site Visit)

Temple Street, as an inclusive space, carries traces from different Chinese provinces, demonstrating cultural hybridity. We observed a wide range of Chinese food culture on Temple Street, ranging from “daipaidongs” (street-side restaurants without air-conditioning) to Sichuan-Chongqing hotpots. In particular, this cross-culture hotpot is greatly valued in the Chinese society because it serves as the food choice for reunion. These traces from Chinese Provinces appear in Temple Street because their eating culture (such as Spicy Hot Pot) has become popular in Hong Kong, and are therefore with great demand. Glocalization (the practice of introducing foreign culture to a place while adjusting foreign cultural elements in order to adapt to local culture and beliefs) is also exhibited on Temple Street as shops which previously predominantly offered traditional Southeast Asian products started selling local snacks to lure local customers. It fully evinces the fusion of foreign culture with local culture, exhibiting culture hybridity on Temple Street. Under the envisaged globalization, the presence of non-materialistic traces like other religions such as Buddhism (Figure 5) and Hinduism have also rooted a sense of identity in both Chinese and Southeast Asians.

Night

After sunset, the functionality of Temple Street changes significantly. The street is most well-known for its flea market at night (Figure 6). Since the night market mainly provides products such as men’s clothing, electronic devices and second-hand antiques, which are predominantly for male customers, the street is also called “Men’s Street”. Moreover, as the stalls sell low-priced merchandise and allow consumers to bargain, the market is also hailed as the “Nightclub of Civilians” in Hong Kong. From the aforementioned, one can observe that nightlife on Temple Street tilts towards satisfying capitalistic and materialistic needs, where entertainment and economic benefits are put on a pedestal.

Figure 6: Temple street night market

(Source: https://bit.ly/2JkntwN)

Figure 7: Fortune-Telling counter in temple street

(Source: https://bit.ly/3oksHXR)

Additionally, fortune-telling (Figure 7) and divinatory booths are also a significant component of Temple Street at night. In the early years, these booths were only set up by Fengshui and face-reading masters. Nowadays, we can discover a lot of western divinatory methods in the stalls, such as tarot, runes and astrology. Chinese and Western religions, when juxtaposed together, create a particularly mesmerizing scenery. This reflects the inclusiveness and openness in our society given the local residents’ acquiesce in foreign culture. As western culture blends into that of Chinese, the discrepancy between them are bridged, thereby inducing cultural fusion, which possess characteristics that lure both Chinese and Western people.

Moreover, food stalls, dubbed as daipaidongs (Figure 8), provide various local dishes that represent Hong Kong’s street food culture. The lyrics in the songs of buskers contain different characteristics of the street and some heartfelt wishes of locals, showing the close-knit bonding between the civilians and their neighbourhood, thus enhancing the sense of belonging for local residents.

Figure 8: Daipaidong in Temple Street

(Source: https://bit.ly/2Vpiu07)

Ideological conflict in the function of Temple Street between day and night

According to Paul Carter, the author of The Road to Botany Bay: An Essay in Spatial History, place-naming is a powerful process in which “space is transformed symbolically into a place, a space with a history.” (Carter, 1998) The eponymous name “Temple Street” is derived from the plenitude of Chinese temples along the street, evoking an air of spiritual cleanliness and holiness, as well as the reverence from its historical weight. However, Temple Street is also known for its transformation into a red-light district at night, given the selling of adult sex toys (Figure 9) and loitering of prostitutes on the street (Figure 10). The irony lies in the fact these morally “impure” and socially undesirable activities simultaneously coexist on the same street which attracts worshippers to pay their respects to the gods (Figure 11).

Figure 9: Shop selling sex toy

(Source: https://bit.ly/3qkortg)

Figure 10: prostitutes loitering

(Source: https://bit.ly/2Jkq7CJ)

Figure 11: Temple with offerings to Gods

(Source: Taken during Site Visit)

Ideologically, there could not be a greater contradiction to Carter’s belief in the power of naming, as it seems that the process of place-naming has transformed a space into representing something symbolically opposite. It would be reasonable for one to think that at least some devout worshippers would be outraged at having these inappropriate and morally shameful activities taking place at such close proximity to a religious site. Yet, there seems to be a general lack of protest in reality.

One interpretation could be the inclusiveness in Temple Street owing to the general acquiesce in various cultural activities. Temple Street’s historical and religious background plays a cameo role in creating a sense of identity and emotional attachment in the street-users, instead most street users (businessmen, street singers, immigrants) treat it as a cultural hub. Another interpretation may be telling of Hong Kong people’s pragmatism, which prioritizes practicality over cultural significance regarding the use of space. Moreover, time itself seems to act as a boundary between these two antithetical cultural traces on Temple Street, with daytime belonging to a place of worship and normal functions of shopping and dining, and nighttime belonging to the underworld of street gangsters and prostitution.

Sense of Place – one of the elements of ‘place’

Overall, regarding the sense of place, Temple Street gives a strong sense of belonging to Chinese communities, especially of the lower- and middle-class. The numerous portrayals of the street in old local films may create evoke nostalgia in the older generations, as they reminisce life in the colonial era. It also has an increasingly multi-cultural and diverse spirit, allowing even Southeast Asian communities to call it “home” with its flourishing businesses. The rich religious history and beautiful ancient Chinese temples also instil in locals a sense of pride in their Chinese roots. This pride may also extend to Hong Kong’s international reputation with Temple Street’s increasing popularity among tourists. Lastly, the red-light district and shady activities at night may create a sense of fear among local women, as well as a sense of shame among men who are seen on the street at night.

4. Conclusion

Over the years, Temple Street has transformed from a merely local cultural space to an international tourist spot. Our topic compares the differences between the daytime and night-time function of this street. While some view Temple Street as a religious and holy space, stalls selling sex toys might may give the street a tarnished reputation. On the other hand, the street has become more culturally diverse from the influx of Southeast Asian immigrants who have established their businesses here. Though this gives the street a unique cultural identity, some Chinese culture traces might unavoidably be diluted and it was intriguing to explore the kinds of traditions that are fading in particular. Lastly, we sincerely hope that Temple Street’s rich historical, religious, and cultural traces, would be preserved by the government, so as to allow future generations to appreciate the physical manifestation of cultural diversity.

References

Withers, C. W. J. (2009). Place and the "spatial turn" in geography and in history. Journal of the History of Ideas, 70(4), 637-658. Retrieved from http://easyaccess.lib.cuhk.edu.hk.easyaccess2.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.easyaccess2.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/docview/1272094687?accountid=10371

Carter, P. (1988). The road to Botany Bay: An essay in spatial history. London: Faber and Faber.

Lee, R., Castree, N., Kitchin, R., Lawson, V., Paasi, A., Philo, C., ... & Withers, C. (Eds.). (2014). The SAGE Handbook of Human Geography, 2v. Sage.

Cover photo retrieved from: https://hk.trip.com/travel-guide/hong-kong/temple-street-10524210/ clave