1. Introduction

Located in Wan Chai (Figure 1), Lee Tung Street (LTS) was once famed for its clustering of printing shops. Throughout the years, the street has undergone drastic alterations, from a printing street to a wedding card street, from a bypath to a side street. After the redevelopment, it has become a pedestrian zone filled with luxurious, high-end shops and has been donned a new name Lee Tung Avenue (LTA) (Ko, 2010).

Figure 1: Location of LTS

(Source: Google Map)

How do the interactions between different powers such as the government, property developers and and the residents have shaped Lee Tung Avenue and modified its cultural traces? What does it reflect about the relationship between cultural heritage and redevelopment? These are the questions this project aims to address from a cultural geographical approach, with the aid of Henri Lefebvre’s theory of Spatial Triad.

2. Cultural geographical perspective in use

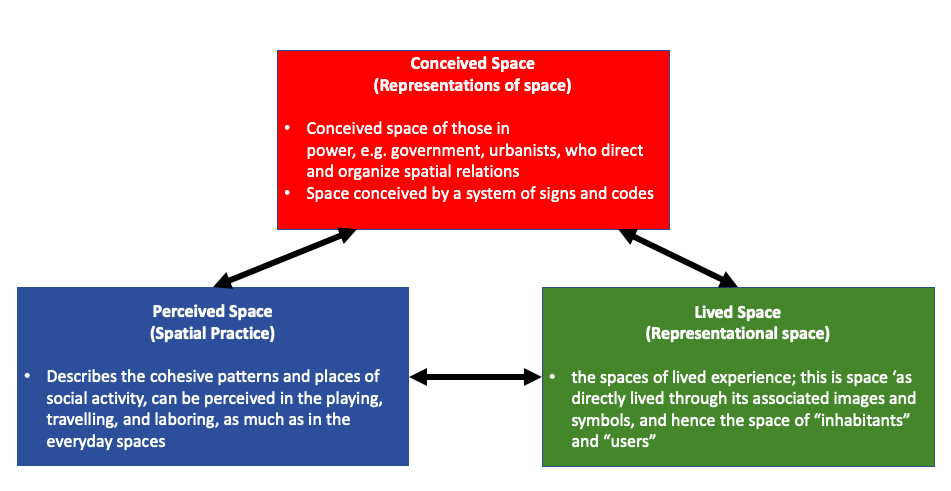

Henri Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad includes three spatial dimensions (Table 1). Conceived space suggests the space that is planned, directed and organized by the power, for example, an urban planning map. Perceived space describes what people do in the space planned by those in power, such as selling wedding cards. Lived space indicates some symbols or values imbued by what people do, for instance, social ties. By using this framework (Figure 2), how different cultural traces of LTS have been produced through the interplay between the place, dominating power generated from conceived space, and resistance produced in perceived space and lived space will be analyzed in this summary

Figure 2. Henri Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad

(Source: Lefebvre, 1991)

Table 1. Framework of using Spatial Triad in LTS

(Source: Inspired by URA, 2003; Watkins, 2005; H.W. Wong & P. Wong, 2007; URA, 2007; Huang, 2009; Ko, 2010; Ng, et al., 2010; Gieseking, et al., 2014; Wong, 2016; Tsang & Zhang, 2019)

|

Dimensions |

Before redevelopment |

After redevelopment |

|

Perceived Space |

1. Sold traditional Chinese style products e.g. wedding cards, red packets

2. Low-income residents residing on the upper floors of tong lau

3. Residents helping and caring for one another. More interactions between neighbors |

1. Chain stores selling branded products like accessories, cosmetics etc.

2. High-income residents residing in The Avenue à gentrification

3. Original residents dispersed; the neighborhood disappeared

|

|

Lived Space |

1. Known as Wedding Card Street, having rich cultural values and uniqueness, as it was the only street in Hong Kong with the theme of wedding cards

2. Residents formed a close-knit community which is filled with warmth

|

1. Lost the meaning of Wedding Card Street. Turned to more high-end and commercial, loss of uniqueness

2. Loss of social ties, the history of the place and the residents’ connection to the place are lost |

|

Conceived Space |

1. During the 1950s, clusters of printing and wedding card making shops in LTS, and other retailers selling related items

2. Mandated by the government to supervise illegal publications easily |

1. In 2007, a redevelopment project launched on turning LTS into a “first-class shopping and leisure center”

2. “The wedding theme would be maintained”, said by the Hopewell Holdings Limited in 2013

3. Most of the printing shops having been replaced by luxury chain stores and high-quality boutiques, restaurants & hotels etc. |

3. Empirical analysis

A. Dominating power

In the case of LTS, the dominating power is represented by the Urban Renewal Authority (URA) and property developers, i.e. Sino Land Company Limited and Hopewell Holdings Limited. The URA is a statutory body in Hong Kong responsible for urban redevelopment projects. Though it is not a government department, the URA is granted much power and resources by the government and it works closely with the government. These stakeholders used various means to encourage a materialistic and capitalist culture.

First, the URA announced a development concept competition for LTS redevelopment project, in which entries were mainly encouraged to incorporate ideas of pedestrianizing, commercializing LTS and conserving pre-war historical buildings. From this, we can already see how the focus of the project was to make LTS into a center for economic and tourism activities, which is the new conceived space planned by the government.

Second, the URA chose property developers based on their experience and financial strength, showing how it pandered towards the financial interests of profit-oriented companies. Sino Land Company Limited and Hopewell Holdings Limited, which are key players in the real estate market, eventually won. The URA also stressed the importance of creating job opportunities for the construction sector and improving patronage flow. This further encourages the already capitalist mindset in Hong Kong and elevates the status of property developers through governmental recognition. The dominating powers further consolidate their transformative power.

Third, Lee Tung Avenue (the new conceived space), which is the result of the redevelopment project on the site of the original LTS, is a high-end shopping street that barely preserves any pre-existing cultural traces. URA promised to keep the wedding theme in Lee Tung Avenue after redevelopment, but the street is now dominated by international brand chain stores with only two wedding cards shops remained, showing that the dominating power had no genuine wish to preserve the traditional cultural values of LTS.

Overall, it can be seen that an overt focus on the economic benefits by the government and property developers drowns out any room for discourse from a cultural perspective.

B. Resisting power (strategies and concepts)

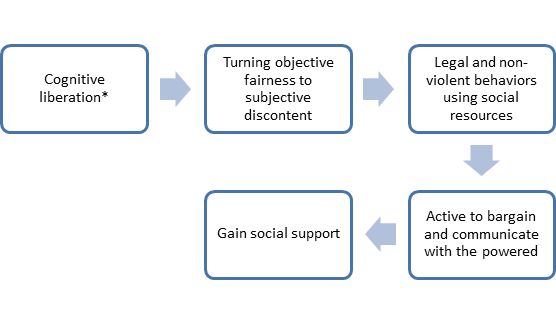

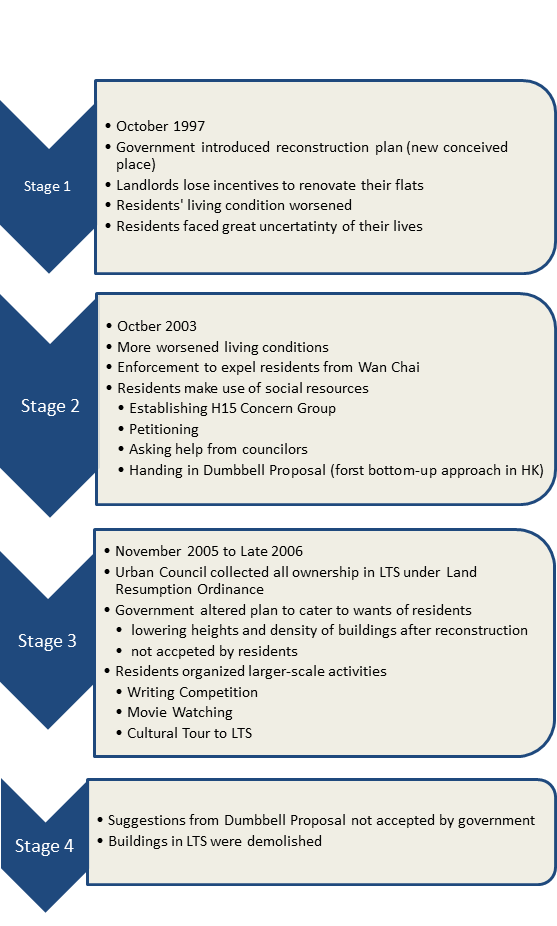

Being the resisting power, the residents, on an individual basis, does not have enough power to fight against the dominating powers. With the help from other parties, they can turn their incentives into actions, creating the ‘power of the powerless’ in the progress. The general strategies mobilized by resisting parties would be presented below (Figure. 3). And the whole protest movement can be divided into four stages (Fig. 4).

Figure 3. Strategies used by General Resisting Power Parties

(Source: McAdam, 1982)

*Cognitive liberation: gradual understanding of political and economic intentions of the powered

At stage 1, they had not yet fully understood the intentions of the powered. While the conceived reconstruction plan ruptured the original stable social network of LTS.

At stage 2, the residents achieved cognitive liberation. They found out the intentions and the inappropriate mobilization of power of the government. In the aspect of perceived space, the daily activities and the close social network had created a sense of belonging among the residents to LTS. They perceive LTS as their home, and it constitutes a large part of their identity. The unfairness fostered a sense of discontent among the LTS residents, turning objective fairness into subjective discontent. They started to make use of social resources and seek help from professionals to organize more resisting activities.

At stage 3, the altered reconstruction plan from the government was not accepted. The H15 Concern Group, formed by residents and shop owners affected by the redevelopment project, organized larger-scale activities, hoping the public would sympathize with their condition. Although the public became more aware of the situation in LTS, creating a force of public opinion that halts the redevelopment project, the LTS protest was not successful in the final stage.

There is an imbalance between the two power. The government could enforce laws that require the landlords to give up their property rights. At the same time, the reconstruction plan was supported by many big developers, who had strong financial base to oppose the resistance. Residents failed to bargain with the governments and developers despite obtaining the public’s support. In the end the resisting power had no actual power at all.

Figure 4. Four Stages of Conflicts between Dominating and Resisting Power

(Source: Xia, 2014)

C. Trends of development

From the case of LTS, the dominating powers enforced changes in the conceived space which provoked changes in the perceived space and lived space. It could be observed that during redevelopment, the old cultural traces of LTS were challenged and replaced by new merging cultures.

This introduces us to a new concept, placelessness. Since place are created when we embody “space” with cultural meanings. Placelessness refer to places that lack cultural diversity and do not reflect distinct local characteristics (Shim & Santos, 2011).

The creation of new cultural landscapes is usually profit-driven. The government may try to maximize the profit return in an urban renewal project. Commercial elements are preferred over cultural elements. The attractions in the city are targeted at the visitors instead of the locals. Which is perfectly reflected in the LTS project. Gentrification that results from redevelopment facilitates the creation of placelessness (Shim & Santos, 2011). Since the aggregation of higher-end shops will out-compete the local businesses which contribute to the unique local landscapes and identity.

Under this trend of urban development, the city’s landscape would appear to be “fabricated”, since the traces of a place would be modified directly by those in power instead of being generated from interactions within the residing community. The newly added elements in the redeveloped area are usually inspired by the characteristics of other places and are visitor-oriented (Shim & Santos, 2011). For instance, The Venetian Macao, a luxury resort located in Macao (Ip), resemblances Venice greatly and even has replicas of several Venetian landmarks. The “unique features” of a place becomes superficial and are not distinct anymore, deviating from their historical roots. For instance, Asian metropolis such as Hong Kong, Seoul and Tokyo may differ little from cities such as Las Vegas and New York. This results in the loss of social and cultural context of a place.

4. Conclusion

In this paper, we deploy Henri Lefebvre’s theory of spatial triad to analyze the changes of the cultural traces before and after the redevelopment of LTS, offering a systematic analysis of how exactly it was altered. Unevenly distributed transformative powers led to the emergence of resistance during the redevelopment period. Albeit adopting different strategies, the resisting powers posed no hindrance when faced with the dominating powers. The resisting power only contributed to the production of some short and temporary cultural traces from the conflicts between the dominating and resisting powers, for instance the banners and the signs being hung across LTS. While the dominating power re-constructed LTS based on their blueprint which focused on morphing LTS into a high-class shopping district, completely changing its cultural landscape.

Using the complete demolition of LTS as a case study, we tried to uncover the trend in redevelopment of decayed urban districts. Renovation of the decaying district is much needed, but it is observed redevelopment plans suggested commonly omit the importance of cultural preservation. Conceived space seems to play a more significant role than perceived space and lived space when drafting up a developmental plan. A balance between cultural heritage and redevelopment has yet to be found. But we believe communication bridges conflicting views. With more discussion, an intermediate solution that merges cultural preservation and economic development would be found.

Footnote

Source of the cover picture: photo by 捲捲和土豆拿鐵部落格, 2017.

References

Adrienne L.G., & Frederik P. (2016). State-led gentrification in Hong Kong. Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland), 53(3), 506-523.

Gieseking J.J., Mangold W., Katz C., Low S., Saegert S. (2014). The Social Production of Space and Time. The People, Place, and Space Reade (pp. 285). New York: Routledge. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.hk/books?hl=zh-TW&lr=&id=b9WWAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA289&dq=Henri+Lefebvre’s+Spatial+Triad+perceived+space&ots=KWWuyJiqw6&sig=hAoXAny8a79Rgg8frlp5cDfz5Js&redir_esc=y#v=snippet&q=spatial%20practice&f=false

Huang, S. (2009). A Sustainable City renewed by “People”-Centered Approach? Resistance and Identity in Lee Tung Street Renewal Project in Hong Kong. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.732.4972&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Ip, K. (n.d.). Asia's largest single-structure hotel building - modern engineering on a grand scale. Retrieved November 18, 2020, from https://www.arup.com/projects/venetian-macao

Ko, P. S. (2010). Intangible Heritage [Master’s thesis, University of Hong Kong]. The HKU Scholars Pub.

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The Production of Space. J.J. Gieseking, W. Mangold, C. Katz, S. Low, S. Saegert The People, Place, and Space Reade (pp. 285). New York: Routledge. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.hk/books?hl=zh-TW&lr=&id=b9WWAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA289&dq=Lefebvre+production+of+spaces&ots=KWWvyHnnEa&sig=s0qcoAcoCgixF3nA2wGpFxuTFkQ&redir_esc=y#v=snippet&q=directly%20lived%20through%20its%20associated%20images%20and%20symbols&f=false

Ley, D, & Teo, S. Y. (2014). Gentrification in Hong Kong? Epistemology vs. Ontology. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), 1286-1303.

McAdam, D. (1982). Political Process, the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press

Ng, M.K., Tang, W. S., Lee, J., & Leung, D. (2010). Spatial practice, conceived space and lived space: Hong Kong’s ‘Piers saga’ through the Lefebvrian lens. Planning Perspectives, 25(4), 411-431.

Shim, C., & Santos, C. A. (2011). Urban Tourism: Placelessness and Placeness in Shopping ... Retrieved November 17, 2020, from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1703&context=ttra

Snow David A., Jr E. Burke Rochford, Worden Worden, Benford Robert D. (1986). Frame Alignment Processes, Micromobilization, and Movement Participation. American Sociological Review, 51(4): 461-481.

Watkins, C. (2005). Representations of Space, Spatial Practices and Spaces of Representation: An Application of Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad. Culture and Organization, 11(3), 209-220.

Wong, H. (2016, February 1). Wedding Card St to be turned into ‘first class shopping’ district, developers accused of backtracking. Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved from https://hongkongfp.com/2016/02/01/wedding-card-st-to-be-turned-into-first-class-shopping-district-developers-accused-of-backtracking/

Wong H.W., Wong P. (2007). 本土工程人 : 陳景輝專訪. Retrieved from https://commons.ln.edu.hk/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=zh-TW&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=利東街&btnG=&httpsredir=1&article=1056&context=mcsln

Urban Planning Renewal (URA). (2003, October 17). URA announced a 3.58-billion redevelopment project in Wan Chai [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.ura.org.hk/tc/media/press-release/20031017

Urban Planning Renewal (URA). (2007, December 24). Wan Chai Lee Tung Street Redevelopment Project [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.ura.org.hk/tc/media/press-release/20071224

Xu, J. (2020, September 15). Culture, space, place and power [Lecture notes].

李維怡(2007)。《黃幡翻飛處—看我們的利東街》。香港:影行者有限公司。

夏循祥(2017)。《權力的生成:香港市區重建的民族志》。北京:社會科學文獻出版社。

呂烈丹 (2007年2月7日)。〈不再在精英的口袋裡—利東街運動對文物保育概念的啟示〉。《明報》。

捲捲和土豆拿鐵部落格,痞客邦。(2017年7月11日)〈香港利東街 喜帖街。灣仔小歐洲步行購物街。香港最新景點〉。取自https://nigi33kimo.pixnet.net/blog/post/117461208