1. Introduction

Kowloon Walled City was a Chinese military fort in Hong Kong, which turned into an enclave after the New Territories were leased to Britain in 1898. During the Japanese occupation, the Walled City was zoned as the Kowloon City Development Zone of British Hong Kong and was narrowed to 2.6 hectares. It used to be the most crowded area containing more than 50,000 residents. It was also an ungoverned settlement controlled by local triads, having a high rate of prostitution, gambling and drug abuse.

In the 1980s, the colonial government decided to demolish the Walled City and it was eventually demolished in 1994. Nowadays, the Kowloon Walled City has become a legendary place in the history of Hong Kong.

In this project, we will study the mysterious despairing Kowloon Walled City from its production of space with the Spatial Triad by Henri Lefebvre.

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

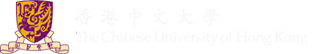

From the perspectives of cultural geography, a place is formed by interactions between geographical context and cultures, which hence create various traces, both tangible and intangible.

![]()

The composition of Kowloon Walled City can be analyzed as:

Figure 1: Kowloon Walled City from Cultural Geographical Perspectives

Noticeably, with the demolition of Kowloon Walled City in 1994, the importance of Geographical Context and Cultures has faded out as most traces, results of the interactions between the two, have disappeared. Its representations have hence become the major traces of Kowloon Walled City nowadays.

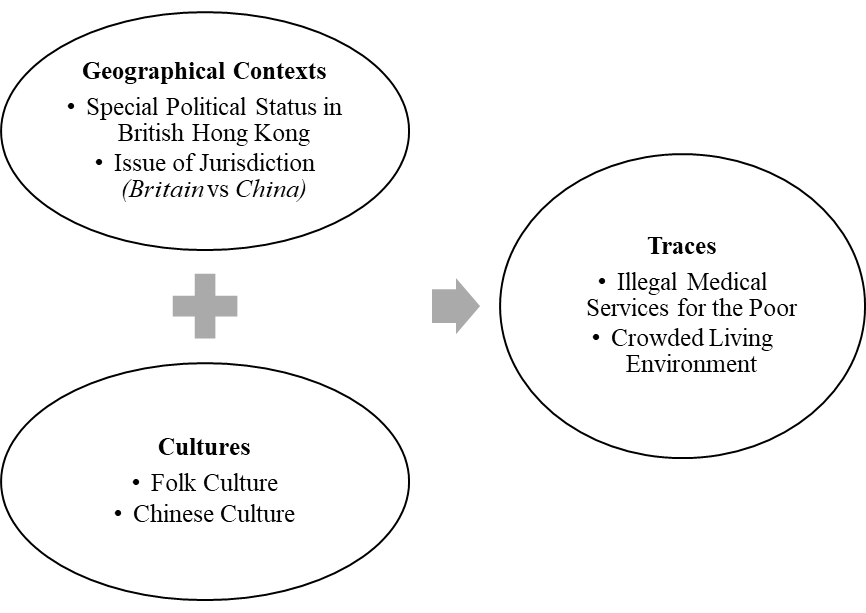

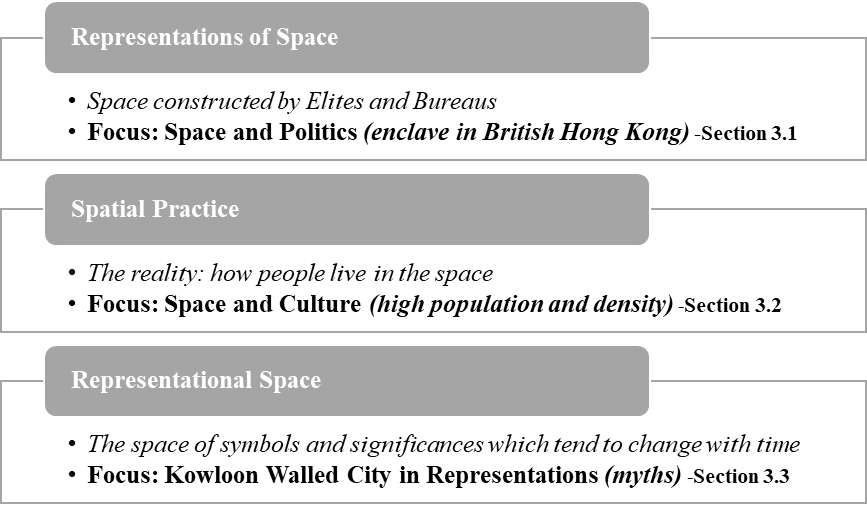

These kinds of memory, in terms of the Spatial Triad by Henri Lefebvre, are Representational Space. The theory states that a space comprises Representations of Space, Spatial Practice and Representational Space which are later defined by Steward (1995) shown in the Figure 2, together with its application to the case of Kowloon Walled City:

![]()

![]()

Figure 2: Kowloon Walled City in Production of Space

The three constituents, later elaborated by Wang (2009), are dependent on each other and cannot live alone. Thus, even after demolition of the City, it can only be concluded that Representational Space has become dominant in its creation nowadays. Later parts of this study will then focus on the Representational Space of Kowloon Walled City, investigating the influences from Representations of Space and Spatial Practice on it, as well as its internal changes with time.

3. Empirical Analysis

3.1 Space and Politics (from representations of space to representational space)

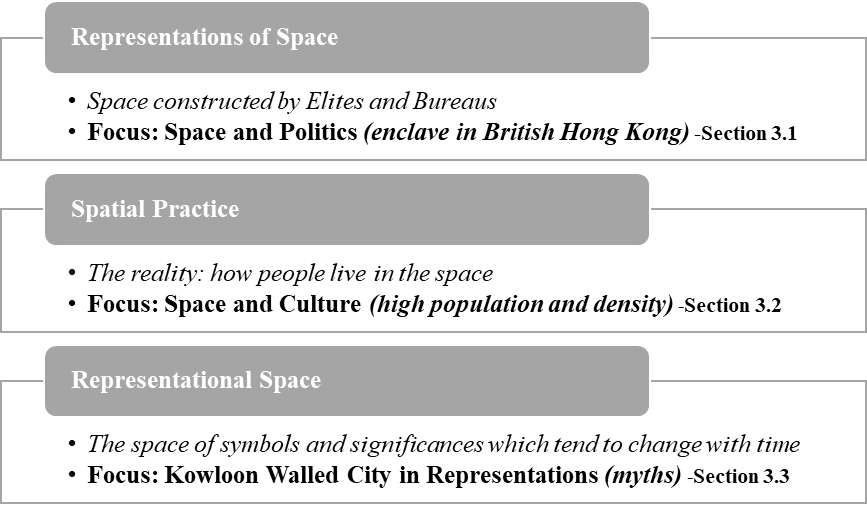

Dirty, poor and ungoverned become the first impression when the Kowloon Walled City is mentioned. The Kowloon Walled City began in the center of Hong Kong where it served as garrison of Chinese government. (Fulton, 2016) It became a place where the Chinese government was reluctant to give up to the Britain and insisted strongly to maintain its jurisdiction after the Convention of Peking. (Sinn,1987)

「所有現在九龍城駐紮之中國官員仍可在城內各司其事」

Figure 3: Convention of the Extension of Hong Kong Territory

(Academy of Chinese Studies, n.d.)

Later Britain took actions to retain its jurisdiction of Kowloon Walled City and claimed it would be administered the same way as other parts of the Colony. However, the fact was both Chinese and British governments declared their jurisdictions of the City, but none put in effort to administrate the city.

Figure 4: Reasons for the Ungoverned State of Kowloon Walled City

As a result, the place gradually became ungoverned and a deficiency of authority, creating the mysterious image of the City, as the saying goes:

「香港政府不敢管,英國政府不想管,中國政府不能管」 (Lu, 2002)

The failure at ruling the City, coupled with its mainly low-class composition, had led to the rise of gangs. This ruling power had continued expanding so greatly that an avalanche of crimes such as drug abuse and fighting were reported. (Kowloon City District Council, 2005) This further undermined the jurisdiction of China and Britain, as well as worsened the image of the City.

Noticeably, under the control of gangs, Kowloon Walled City did not have any development plans. Given that Hong Kong had been continuing its role as an entrepot and even developing manufacturing industries, the physical landscape and living standard of people in Hong Kong had been increasing. However, the ungoverned Kowloon Walled City had most constructions remained how they used to look like, as an old Chinese town with plaques, historical buildings, cannons et cetera. This strong difference had further developed the mysterious, poor dirty image of Kowloon Walled City.

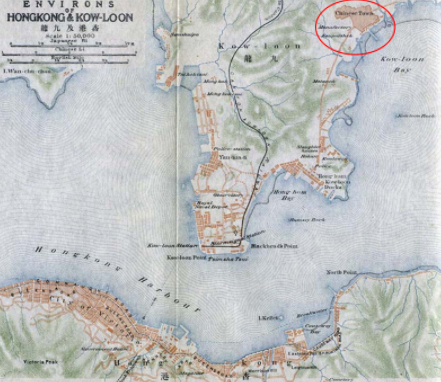

“Chinese Town” was used to represent Kowloon City

Figure 5: Map of Hong Kong and Kowloon in 1915

(An Official Guide, 1915)

3.2 Space and Culture (from spatial practice to representational space)

When we look back at the Kowloon Walled City, it reminds us of dark alleys and a dense population. At the same time, the 25,900 square meters of concrete jungle is what 50,000 people called home. (Routley, 2019) Inside this community is where drug addicts and children walk the same halls, and prostitutes and priests live side-by-side. Despite the different walks of life, inside this vertical village, close bonds were formed between neighbors as the community coordinates to conserve electricity, repair shared infrastructure and organize garbage disposal.

The existence of the Kowloon Walled City caused planes to turn 45 degrees before landing at the Kai Tak airport and the buildings were no more than 14 floors high to avoid collisions with aircrafts. (Routley, 2019) In the dense Walled City, staircases and alleys were interconnected creating a labyrinth where you could walk from north to south without touching solid ground. (Girard & Lambot, 1999) Additionally, because buildings were built side-by-side, many rooms have no windows or natural lighting which makes the City's rooftops an important place to gather, relax and children to play or do homework after school. (“Devil's Paradise”: 1900-1992, n.d.) Hence, the Kowloon Walled City demonstrates communal living where much of the perceived space acts as shared space for the vertical village. Additionally, without the help of architects and engineers, the Walled City demonstrates people can get along just fine without regulations guiding every aspect of life.

Indeed, the Walled City is notorious for a high crime rate. However, contrary to popular beliefs, only a small number of people in the City engage in criminal activities and most are just elderlies living out their retirement. (“Devil's Paradise”: 1900-1992, n.d.) In 1983, the Walled City’s crime rate was declared under control, however, the city was still known for unlicensed doctors and dentists who continued to operate without prosecution. In a sense the Walled City created a shadow economy for Hong Kong as it contained hundreds of unregulated workshops and factories that provided outsiders with lower priced goods and services.

3.3 Kowloon Walled City in Representations (changes in representational space)

After the demolition of the Kowloon Walled City and the handover of Hong Kong, the local imagination of the Walled City has been proactively shifting from a grim, lawless mess to a site of old colonial Hong Kong aesthetic and nostalgia under Hong Kong's social and historical context in recent decade. Back when the Kowloon Walled City was still barely standing in the Kowloon Peninsula as an overly dense slum (before 1993), the City was notorious for its safety and hygiene issues. From drug dealing, prostitution to the consumption of dog meat, these menacing practices scared away outsiders from entering this dark spot of the City and covered it with a veil of mystery. The 1984 Hong Kong film, Long Arm of the Law, managed to capture the overall imagination of lawlessness and hideousness towards the place. This infamous image of the Kowloon Walled City constituted by both facts and rumors had been clouding the locals until new meanings were installed onto the Walled City after the 1997 handover.

As the political ambiguity of the Kowloon Walled City was weaved upon the tension between the British colonial power and Qing/Chinese government, the political significance of the Walled City dissolved after the demolition and handover. Such politically sensitive traces of the site and the habitats were cleansed from the official historical discourse after the handover. (Guan, 2014) Yet, unlike its fading traces, the image of the Kowloon Walled City was widely adapted and discussed amongst many postcolonial media pieces. From book City of Darkness Revisited (2014), TV drama A Fist Within Four Walls (2016) to video game Paranormal HK (2020), the obsession towards the visual and image of the walled concrete conglomerate was obvious. Without the blood stink of slaughtered dogs and suffocating ventilation in the crowded apartment, the history of the Walled City was sanitized and extracted to constitute the well-decorated version of the Kowloon Walled City for nostalgia. This new interpretation of the Walled City would be a product of the postcolonial reflection of Hong Kong people and would play an important role in the constitution of local cultural identity.

4. Conclusion

Using Henri Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad, we were able to study Kowloon Walled City under three interconnected spatial thinking. From Representations of Space, owing to the changes in time and rulership, the conceived space of the Kowloon Walled City with high-rise buildings densely constructed side-by-side was created. This characterized feature has also shaped a unique Spatial Practice there, namely the close bonds between neighbors, the formation of a tight community within the dense area, as well as safety and hygiene issues. Additionally, because of its Spatial Practice, the Kowloon Walled City is shrouded with mysteries and has become a popular Representational Space for lawlessness and poverty. Although the political traces of Kowloon Walled City have slowly faded due to its political sensitivity, the geographical status of the Kowloon Walled City lives on in popular modern media and culture.

Reference

“Devil's Paradise”: 1900-1992. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://mediakron.bc.edu/edges/the-yamen-an-inquiry-into-identity-and-place-in-the-kowloon-walled-city/devils-paradise-1900-1992

Academy of Chinese Studies. (n.d.). Pictorial History: The New Territories were leased to Britain. Retrieved from https://chiculture.org.hk/en/node/1201

An Official Guide to Eastern Asia, Volume 4: China. (1915). Tokyo: The Imperial Japanese Government Railways.

Carney, J. (2013 Mar 16). Kowloon Walled City: Life in the City of Darkness. South China Morning Post: Old Hong Kong. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/article/1191748/kowloon-walled-city-life-city-darkness

Fulton, M. (2016). The History of Kowloon Walled City In 1 Minute. Retrieved from https://theculturetrip.com/asia/china/hong-kong/articles/history-of-kowloon-walled-city-in-1-minute/

Girard, G., & Lambot, I. (1999). City of Darkness Life in Kowloon Walled City. Surrey: Watermark.

Guan, H. Y. (2014). 從歷史裏走出來的九龍城寨 [Kowloon Walled City from History]. Cultural Studies @Lingnan, 43, Article 7. Retrieved from http://commons.ln.edu.hk/mcsln/vol43/iss1/7/

Jones, G. (2011). The Kowloon City District and the Clearance of the Kowloon Walled City: Personal Recollections. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch, 51, 257-278. Retrieved fromhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/23891943

Kowloon City District Council. (2005). 九龍城區風物志 [Story of Kowloon City District]. Hong Kong: Wan Li Book.

Lee, J.J. (2016). Kowloon Walled City Revisited: Photography and Post coloniality in the City of Darkness. Difficult Histories, 6:2. Retrieved from https://quod.lib.umich.edu/t/tap/7977573.0006.202/--kowloon-walled-city-revisited-photography?rgn=main;view=fulltext

Lu, J. (2002). 九龍城寨史話 [History of Kowloon Walled City]. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing.

Routley, N. (2019). This Fascinating City Within Hong Kong Was Lawless For Decades. Retrieved from https://www.visualcapitalist.com/kowloon-walled-city/

Sinn, E. (1987). Kowloon Walled City: Its Origin and Early History. Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 27, 30-45. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/23886841?seq=9#metadata_info_tab_contents

Steward, L. (1995). Bodies, Visions and Spatial Politics: a Review Essay on Henri Lefebvre’s The Production of Space. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 13, 609-618.

Wang, C. H. (2009). Dialectics in Multitude: Exploration into/beyond Henri Lefebvre’s Conceptual Triad of Production of Space. Journal of Geographical Science, 55, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.6161/jgs.2009.55.01