The Transition from Old to New in Kwun Tong Industrial Area

1. Introduction

Kwun

Tong factory district is a unique zone with diversified land-use which

significantly differ from that in the past. These include a mixture of old

industrial buildings, new commercial offices, art and recreational sites and

restaurants. Through examining the phenomenon of old and new alternation in

Kwun Tong industrial area, this project aims to argue that these cultural

traces are strongly shaped and regulated by the changes in socio-economic

developments and community in Hong Kong. This project draws upon Lefrebvre’s

(1991) theory of “Production of Space” to deduce and analyze how these culture

traces illustrate the socio-economic transformations in Kwun Tong.

2. Cultural Geographical Perspective in Use

Cultural

geography integrates the notion of space and place into the

investigation in how cultures work in a specified location in practical

(Anderson, 2015). In other words, cultural geography explores the intersections

of culture and context and seeks out why cultural activities take place in a

specific way in a specific context (Crang, 2013).

Key

concepts included in the theory mentioned above will be defined as follows.

First, culture is comprised of a mixture of human activities, that consist of

social norms, behavioural practices and emotional reaction we take part in

obeying, resist or ignore (Crang, 2013). Therefore, it embodies a broad span of

human life and can never be seen separately from the economy, society or

politics. Second, geographical context; often related to physical landscapes,

locations and nationalities; refers to the material and non-material “things”

like historical events and values that influence what humans do (Crang, 2013).

Third, traces can be considered as tangible “objects”, like statues and

buildings, and non-tangible “things”, such as values (Crang, 2013).

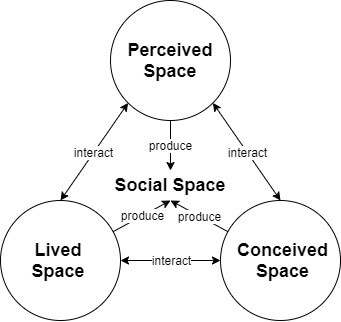

Lefebvre (1991) proposed the theory of “Production of Space”, which conceptualized space, consisting perceived space, conceived space and lived space, as a social product (see Fig. 1) (Lefebvre, 1991; Wang, 2009). Perceived space is somewhere containing spatial practice involving usual activities and values that pre-exist in the space, while a conceived space consists of conceptualized rules and regulations that control the discipline of space (Lefebvre, 1991; Wang, 2009). Last, the lived space is a representation of space that appears after the prior two spaces merged. Social space is hence produced by the intersection of the three spaces (Lefebvre, 1991; Wang, 2009). Therefore, we had used this theory, which resonates with the cultural geographical perspective we seek to draw upon, as an analytical framework to explain how the concepts identified above explicate our empirical observations.

Figure 1. An illustration of the relationship among the three spaces in the "Production of Space" . (Source: Lefebvre, 1991).

3. Empirical Analysis

‘Production

of Space’ involving the intersection between culture and geographical context,

is mainly guided by human beings. There are three primary

stakeholders: government, factory buildings’ owners and users, who are

with different level of power in influencing the old and new alternation in

Kwun Tong. The corresponding three spaces and the interaction between

stakeholders will be demonstrated below.

The Perceived Space

The old Kwun Tong industrial area was produced based on historical events and human’s value. Kwun Tong, which has witnessed Hong Kong becomes a superior industrialized city in South-east Asia, is the earliest developed district in the urban area. In the early 1940s, refugees moved from mainland China to Hong Kong to seek asylum due to civil war, bringing a lot of capitals and cheap labour force to the city (Hong Kong Tourism Board [HKTB], n.d.; Kwun Tong District Council [KTDC], n.d.). Later, the embargo imposed by the United Nations in the 1950s triggered Hong Kong’s economic reform to start light industry (HKTB, n.d.; KTDC, n.d.). Numerous industries then appeared in a sudden, creating a massive demand for industrial areas. The industrial development of Kwun Tong reached golden times from 1965 to 1985 (Energizing Kowloon East Office [EKEO], 2014). Moreover, its products accounted for 18% of the total productivity of Hong Kong in the 1980s, reflecting its importance in the city’s economy (EKEO, 2014). At that time, the textile industry was the dominant business in Kwun Tong.

Besides, during that period, most people lived in Kwun Tong were refugee, immigrates and workers, who were mainly grassroots. They usually lived in low-cost houses, where they needed to share facilities such as kitchen and washroom with their neighbours. Despite the poor living conditions, they were still industrious to work, which revealed Hong Kong people’s emphasis on the economy and the Lion Rock spirit. Nevertheless, Kwun Tong industry started to decline in the 2000s after a wave of the relocation of many entrepreneurs’ production lines to Mainland China, where provided cheaper labour and production costs, due to her ‘reform and opening-up’ later (EKEO, 2014; HKTB, n.d.; KTDC, n.d.).

The Conceived Space

The government, possessed the dominate transformative

capacity, had proposed the “Energizing Kowloon East” (EKE) as the blueprint for

the redevelopment and revitalization of Kwun Tong industrial area. It aimed at

reconstructing Kwun Tong into a second Central Business District

(CBD) of Hong Kong, which was influenced by the transformation of the

economy (EKEO, n.d.). In the Conceptual Master Plan 2.0 under EKE, goals had

been set to improve the surrounding environment in the industrial area, which

illustrated the additional emphasis toward human’s standard of living (EKEO,

2014).

To

implement these, she changed the land use of regarding zone from industrial to

commercial in 2001, amended several regulations in 2010 and established

Energizing Kowloon East Office in 2012 to support the project (EKEO

n.d.) . First, in terms of Cap. 545 Land (Compulsory Sale for

Redevelopment) Ordinance, the amended ordinance lowered the application

threshold for compulsory sale orders of industrial buildings inside

non-industrial zones from 90% to 80% of ownership (GovHK,

2017; GovHK, 2019; Department of Justice [DJ], n.d.). This addressed the

problem of fragmented ownership in flatted Kwun Tong industrial

buildings. Second, the wholesale conversion of industrial buildings in

“Industrial”, “Other Specified Uses” annotated “Business”, and “Industrial” zones

is liberalized (GovHK, 2017; GovHK, 2019; DJ, n.d.). The

original waiver fees incurred to the owners in the course of the application of

usage conversion of industrial buildings are exempted. Third,

the government relaxed the waiver application policy of individual units in

existing industrial buildings to encourage the arts and cultural sectors and

creative industries to operate. Owners are no longer required to make separate

waiver applications and pay waiver fees, so long as the altered uses of industrial

units are permitted under the planning regime (GovHK, 2017; GovHK,

2019; DJ, n.d.).

The Lived Space

The transformed land use and activities nowadays, which was

found out in our field trip, are developed under the convergence of the two

above spaces. Firstly, it was found that there is a diminishment of tradition

factory belt and enlargement of the commercial zone, which consists of newly

emerged hotels, office buildings, places of entertainment and restaurants.

Secondly,

it was discovered that cultural and creative industries, including music

performance site and the art museum, has been introduced into those unused

factories’ units.

Figure 2. An Art Museum in Kwun Tong. (Source: Authors).

Thirdly, it was also

realized that several recreational facilities have constructed in the Kwun Tong

Promenade located near the sea (See Fig. 9-12). All these present as new traces

as the result of the execution of conceptual space.

Figure 3. Recreational facilities in Kwun Tong Promenade. (Source: Authors).

The interaction between

stakeholders will be further demonstrated as follows. As mentioned previously,

in conceived space, the government proposes plans and

implements policies, while the other

two stakeholders interact with each other in perceived space and

lived space and either adapt or contend against the redevelopment

plan. The three stakeholders influence and counterbalance with one another,

resulting in a representation space (lived

space).

On the one hand,

regarding the industrial land use of factory buildings. First, the factory

buildings’ owners were allowed to rent their units legally without paying

any additional fee to non-industrial land users. Some merchants operate

the business with potentially higher market value and can afford a higher rent,

due to the change of governmental policies. Therefore, the factory owners can

no longer enjoy cheap rent as before and have to either pay high rent

or to find another place to operate. Otherwise, their factories had to close

down.

On the other hand,

concerning the non-industrial land use of factory buildings, as mentioned

previously, factory buildings’ owners no longer need to reject or paid an

additional fee for tenants with other land-lease purposes. Instead, they can

rent out their units as, for example, studio, design and media production,

printing and publishing units legally. Consequently,

the non-industrial users do not need to hide

their reason for renting units from industrial buildings and

operate publicly, which facilitates promotion and flourish

of their unique culture.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, the

phenomenon of transformation in Kwun Tong industrial area’s cityscape can be

explained by the theory of “Production of space”. The corresponding zone had

been reconstructed gradually from a manufacturing quarter or “perceived space”

to a place accommodating various land use for business, trading and

recreational purposes, also known as “lived space” containing changed traces.

The progression was made possible with “conceived space”, which is the urban

development plan and complementary building codes, under the interactions of

multiple stakeholders including the government, users and the land developers

and their altered values. Even though multiple theories can as well be used to

justify the old and new alternation in Kwun Tong factory belt, cultural

geography concludes the result of intertwining of social aspects, making the

research context more comprehensive.

Reference

Anderson, J. (2015). Understanding

cultural geography: places and traces. Routledge.

Crang, M. (2013). Cultural geography.

Routledge.

Energizing Kowloon East Office. (2014). 九龍東工業傳統及公共藝術/城市設 計潛力研究. Retrieved Nov 5 ,2019, from

https://www.ekeo.gov.hk/filemanager/ content/whatsnew/IHS_executive_summary_chi.pdf

Energizing Kowloon East Office. (n.d.).

Retrieved Nov 7, 2019, from https:// www.

ekeo.gov.hk/tc/vision /index.html.

Hong Kong Government. (2017, June 21). Press

Releases–Legislative Council: Using

Industrial Building Units for Cultural, Arts

and Sports Purposes. Retrieved Nov 9, 2019, from,

https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201706/21/P201 7062100474.htm

Hong Kong Government. (2019, Feb 1). Press

Releases– Relaxation of Waiver

Application for Existing Industrial Buildings. Retrieved Nov 9, 2019, from https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201902/01/P2019020100743.htm?

Hong Kong Tourism Board. (n.d.). Kwun

Tong. Retrieved Nov 5, 2019, from

http://www.discover hongkong

.com/tc/see-do/neighbourhoods/kwun-tong.jsp

Kwun Tong District Council. (n.d.). Kwun

Tong History. Retrieved Nov 5, 2019, from https://www.kwuntong.org.hk

/tc/history.html

Laws Compilation and Publication Unit. (n.d.).

E-legislation. Retrieved Nov 9, 2019, from https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The Production of

Space (Vol.142). Blackwell: Oxford.

Wang Zhi-hong. (2009). 多重的辯證列斐伏爾空間生產概念三元組演繹與引申. 地理學報, (55), 1-24.

**Noted that all photos were taken by group members in Kwun Tong Industrial Zone on 9th November in 2019.**