The Cultural Geography of Public Housing in Hong Kong

1. Introduction

As a home for 3.3 million people and almost half the population of Hong Kong, public housing complexes have remained pivotal to the construction of local identity and Hong Kong culture (Vetter, 2019). Despite drastic changes in their appearance over decades, many of the public rental estates have established themselves as one of the most renowned cultural and historical relics of local culture (Hui, 2018). This project aims to investigate how the architectural designs of public housing estates, the histories of socio-economic development and their rich cultural values have co-evolved over time.

Figure 1. Choi Hung Estate – A Slab Public Housing Estate in Kowloon (Photo by Kara M/ CC BY 3.0)

The project adopts a cultural geographical perspective and attempts to understand how the geography of a "space" interacts with social development, thus creating a "place". By utilizing the concept of cultural traces, we aim to examine how their designs coincide with the course of Hong Kong's development, including impacts of rapid economic advancement, changes in social values and traditional Chinese culture on the design of public housing estates.

2. Cultural Geography Perspectives in Use

Anderson (2015) articulated that a "place" is formed by the interactions and co-existence of different cultural traces which reflect the local cultural order. While the cultural order is continuously constructed and deconstructed, these cultural traces may capture how various social values and ideologies have changed over time. Inspired by these theories, this report adopts four major perspectives - structural, spatial, auspicial and commercial - to analyze how the cultural traces of public housing complexes have evolved and transformed since the 1950s. Table 1 summarizes these perspectives and analytical focus.

Table 1. A summary of the four major perspective and analytical focus.

|

Perspective |

Definition |

Analytical focus |

|

Structural |

The way in which parts of a system or object are arranged. |

The layout and design of individual flats of public housing estates. |

|

Spatial |

The position, area and size of things. |

The master layout of public housing estates, the positions of buildings and facilities. |

|

Auspicial |

Good omen and the indication of future success. |

The naming methodology of public housing estates, the analyzation of public housing block designs using Feng Shui. |

|

Commercial |

Buying and selling things. |

The shopping malls of public housing estates and the variety of shops. |

3. Traces of Cultural Transformation and Integration

The history of public housing traces back to the 1950s. On Christmas day, 1953, a severe fire broke out in the squatter area in Shek Kip Mei, and more than 50000 people lost their homes overnight. In response to this crisis, the government built several blocks of resettlement housing in the next year - presently known as Shek Kip Mei Estate - marking the beginning of public housing in Hong Kong (Hui, 2018).

Structural design: from a livable space to a living space

The living conditions of public housing have greatly improved since the 1950s. The earliest public housing blocks constructed in the 1950s provided poor living conditions for its residents. The Mark 1 Resettlement Blocks, for example, are only equipped with shared toilets and shower rooms, and a 24 sq. ft. per-capita living area as opposed to the legal requirement of 35 sq. ft (香港房屋的變遷", n.d.). A kitchen is non-existent.

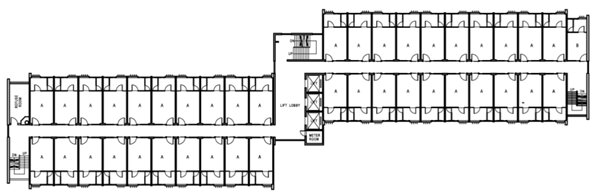

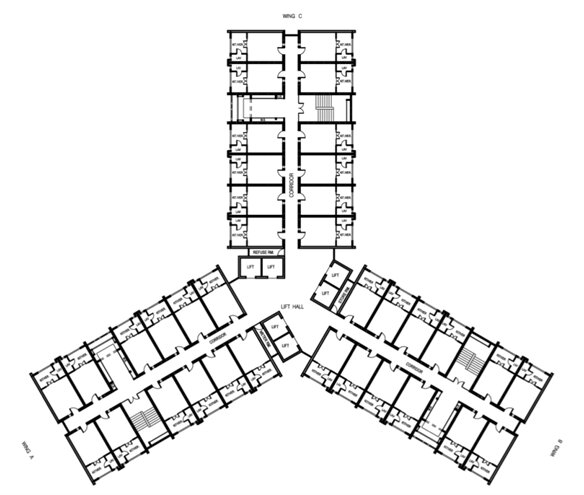

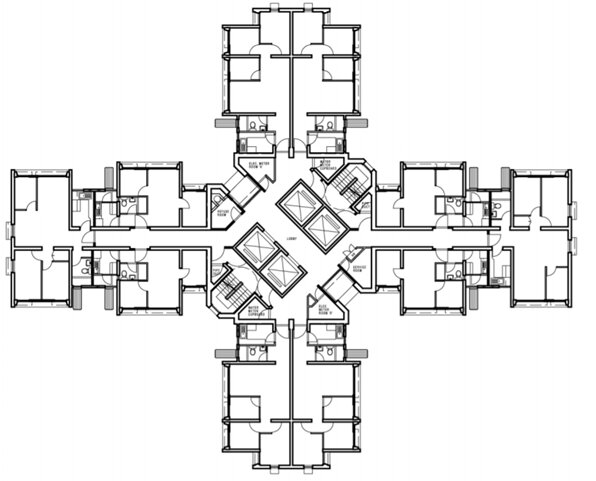

Owing to the revitalized economy in the 1970s and improved social welfare systems, the desire for better living conditions flourished and has greatly influenced the designs of public housing estates since then. Individual toilets and kitchens were introduced to each flat in the new designs of Slab (Figure 2) and Twin Tower blocks. Residents no longer needed to cook and shower on the balcony. The living conditions were further improved in the 1980s with respect to improvements in the local economy. The introduction of Trident Block (Figure 3) design has marked the first type of block whose flats are designed to enable subdividing of bedrooms. Flats of the Harmony blocks were highly standardized due to the use of modular and prefabricated components. While emphasizing on a comfortable living environment and space in the modern era, the latest designs of Concord (I) and New Cruciform (Figure 4) in the 1990s till 2000s bears striking resemblances to private housing blocks, with a smaller (8-10) number of flats on each storey, larger areas for each flat, and pre-set bedroom layouts (香港房屋的變遷", n.d.).

Figure 2. The layout of Standard Block Slab (Link 1 = 180o), a prominent design for public housing estates in the 1970s (Reprinted from "Standard Block Typical Floor Plans", The Housing Authority. 2016, Sept. 5.)

Figure 3. The layout of Standard Block Trident, a prominent design for public housing estates in the 1980-90s (Reprinted from "Standard Block Typical Floor Plans", The Housing Authority. 2016, Sept. 5.)

Figure 4. The layout of Standard Block Concord 1 (Option 1), a prominent design for public housing estates in the 1970s (Reprinted from "Standard Block Typical Floor Plans", The Housing Authority. 2016, Sept. 5.)

The privacy of public housing flats has also been enhanced to transform the “livable space” into “living space” in public housing estates. While flats of earlier designs such as the Mark 1 blocks only provide one corridor-facing window, which wraps around the building for the residents, newer designs in the 1970s, like the Twin Tower or Linear Blocks, presented the residents with more windows facing the corridor. Nevertheless, issues of privacy still remained unsolved since it allowed outsiders were able to peek into the flats. Such problems have not been alleviated until 1984 with the construction of Trident blocks in May Shing Court (美城苑) and Mei Lam Estate (美林邨) (Lau, 2016; "香港房屋的變遷", n.d.).

The structures of public housing have been improved over the years, with more basic facilities within the flat and a larger per-capita area. This process coincides with the period when Hong Kong experiences an economic boom (From 70s to 80s, the first Twin Tower block was finished in 1970) (Lau, 2016; "香港房屋的變遷", n.d.). It can easily be inferred that as the economy boomed and the society generally became more affluent, more comfortable housing became a consensus across various stakeholders including the government, especially for those who grew up in the Resettlement Areas, which were notorious for their poor condition. This reflects a paradigm shift in the social ideology for residential space from "quantity" to "quality" and from a "livable space" to "living space".

Spatial Design

In some sense, the spatial designs of public housing estates also follow similar trends. The early resettlement areas contain very little public and leisure facilities, aimed only at cramming as many blocks as they can. An example is Tsz Wan Shan Estate, with 66 resettlement blocks, and only one playground at the middle of the estate.

For these early estates, public spaces are mainly located within the building itself, like corridors, shared bathrooms and lift lobbies. These common areas are being relocated to outside the building now, and there is usually more than one playground or one park in the same estate. Newer estates also contain more public facilities such as schools, shopping malls and public transport interchange. The layout of buildings also becomes important. Architects, under community planning, take minor details such as microclimate, aesthetic details and accessibility of premises into consideration ("Upper Ngau Tau Kok Estate", n.d.). Greenery is also common within estates.

While the spatial designs generally have become more pleasing, the close relationship between tenants of the estate, as reflected in the increased amount of public facilities in estates remained unchanged. While socializing in corridors in the past, they are now carried out in parks and public areas. The increased public and recreational facilities help residents create a close relationship and a pleasing living environment, in line with the emphasis on quality housing.

Auspicial Perspective: Wishing for Prosperity and Good Luck

Chinese traditions and culture are deeply embedded in the design and naming of the public housing complexes. While most of public housing estates are built in a specific pattern, the culture for naming these multi-storey complexes with word patterns that symbolizes luck and blessings to its residents has remained unchanged since the 1950s. One example would be the naming patterns in Lek Yuen Estate (瀝源邨) and Fung Wo Estate (豐和邨) in Shatin. Despite the fact that the two estates were built in the 1970s and 2010s respectively, the strong emphasis on rituals and blessings in the naming process stayed crucial. The first Chinese character of the seven buildings in Lek Yuen Estate can form a phrase that means prosperity, luck and longevity (榮、華、富、貴、福、祿、壽). A similar pattern can also be found in the naming of the three building blocks of Fung Wo Estate indicating peace, safety and happiness (順, 安, 悅).

Figure 5. A Water Fountain at Lek Yuen Estate - The only water fountain found in any public housing estate in Hong Kong (Photo by WiNG/ CC BY 3.0)

Feng Shui (風水) is also accentuated in architectural designs of the public housing estates. These housing complexes can be categorized with respect to their shapes, such as cruciform, H-shaped, Twin Towers and Trident. While different architectural styles may epitomize different values and beliefs, their designs, in general, reflect the residents' expectations and wishes for prosperity and respect, as well as avoidance from sickness and death. For instance, the H-shaped public housing estates, such as Sha Kok Estate (沙角邨) and Sun Chui Estate (新翠邨), are constructed in the shape of an “H” or the Chinese character of jobs (工) (Koo, n.d.).

Commercial perspective: Changing traces of localness and wholesale development

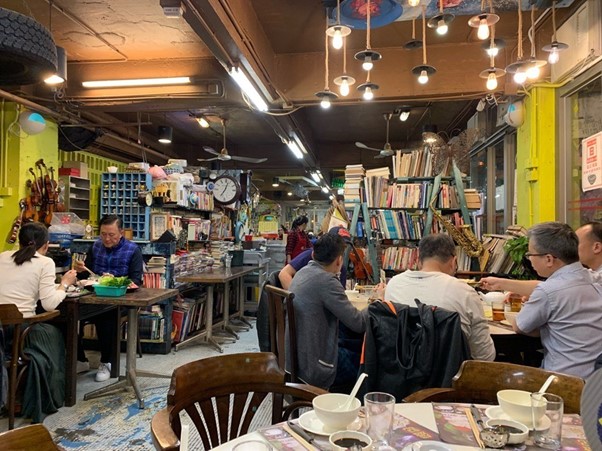

Public housing estates also provide intriguing examples to the study how the emergence of new ideologies of globalization and wholesale development reconstruct these cultural traces. In the past, local shopping malls were mainly composed of small-scale local businesses like stationery shops, local bakeries, Cha Chaan Teng (茶餐廳) and Dai Pai Dong (大排檔). These shops emphasize on their locality and sense of place and community, which were much preferred by the older generations.

Figure 6. Shing Kee Restaurant – a 50-year-old Dai Pai Dong located in Lek Yuen Estate, Shatin (Photo by nevertoosweet/ CC BY 3.0)

Under globalization and waves of enclosure development, these shops, however, have slowly been outcompeted and replaced by international brands and local chain stores, which own plentiful resources of plenty to afford higher rents. These chain stores are generally more popular among the younger generation, who dines in chain stores for a classier and high-end dining experience rather than in an old-fashioned Cha Chaan Teng. At the same time, these shopping malls underwent drastic renovations, such as installing air-conditioning, changing the lighting system, exchanging floor tiles for marble-Esque floors, to fit their prestigious brandings. The old traces filled with localness, compassion and warmth, were wiped out and transformed into a modern, commercialized, international, and yet aloof environment. The commercial traces of public housing have been transformed under the influences of enclosure development.

Public housing is a unique cultural landmark in the modernization of Hong Kong. Representing the shift of socio-economic conditions, living standards, and social values since the 50s, it reflects relationships and beliefs of its residents, and marks the traces of globalization. We argued that the development of public housing is inalienable from the socio-economic development of Hong Kong, which is reflected in the livelihood and beliefs of Hong Kong people of different generations. These traces will continue to be constructed and deconstructed, reflecting an influx and development of new ideologies in the future.

References

Anderson, J. (2015). Understanding

cultural geography: places and traces. Routledge.

Hui,

M. (2018, August 09). Public Housing for Some, Instagram Selfie Backdrop for

Others. Retrieved September 21, 2020, from

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/09/world/asia/hong-kong-instagram-photography.html

Lau,

C. P. (2016, January 16). 從房屋看香港歷史. Retrieved from https://commons.ln.edu.hk/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1001&context=jchkhlp_talks

Standard Block Typical Floor Plans. (2016,

September 05). Housing Authority. Retrieved from https://www.housingauthority.gov.hk/en/global-elements/estate-locator/standard-block-typical-floor-plans/index.html.

Upper

Ngau Tau Kok Estate. (n.d.). Retrieved September 21, 2020, from

https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%89%9B%E9%A0%AD%E8%A7%92%E4%B8%8A%E9%82%A8

Vetter,

D. (2019, January 19). Why public housing shortfall will remain a thorn in Hong

Kong's side. Retrieved September 21, 2020, from https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/society/article/2182106/why-public-housing-shortfall-will-remain-thorn-hong-kongs

香港房屋的變遷. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.fed.cuhk.edu.hk/history/history2005/teach_s3_03.pdf